Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Boho meets bobo bozo: opposites attract in New Wave–icon Anna Karina’s endearing 1973 directorial debut.

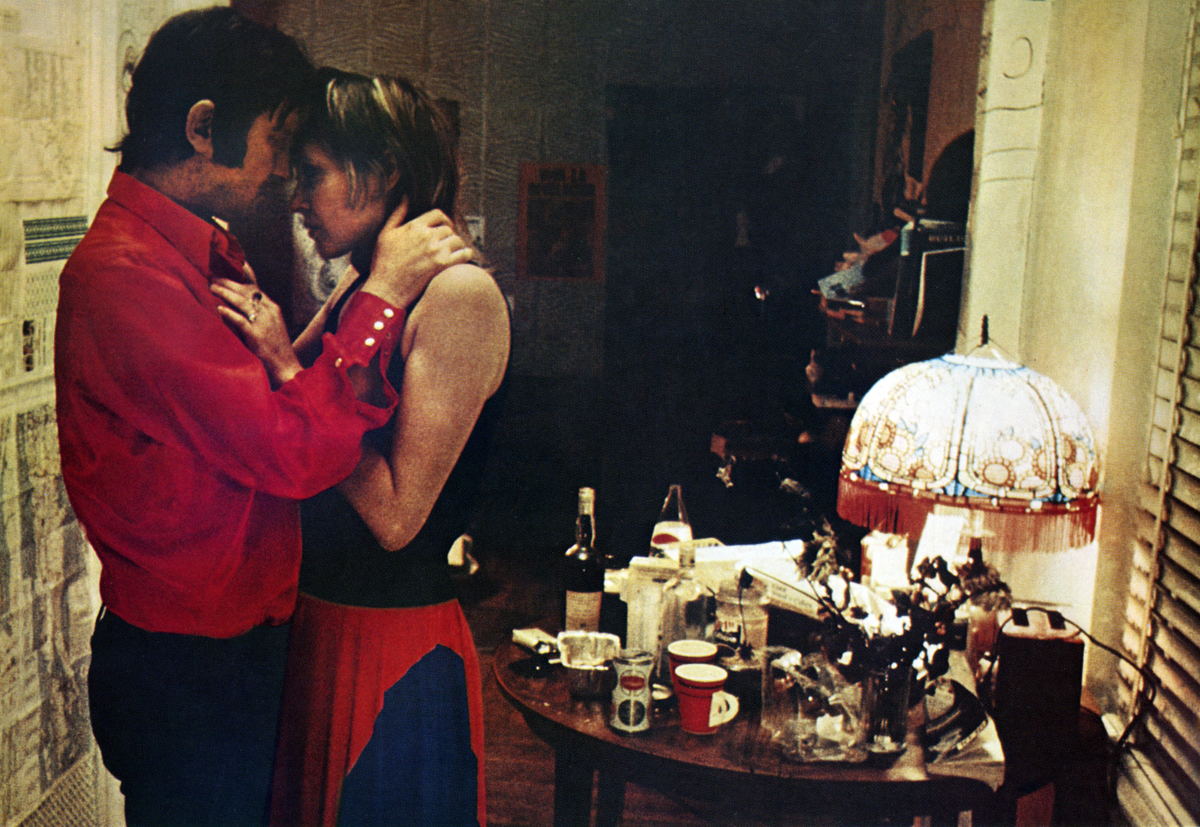

Anna Karina as Julie Andersen and Michel Lancelot as Alain Rivent in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

Vivre ensemble, written and directed by Anna Karina, screens November 12, 2022, Light Industry, 361 Stagg Street, suite 407, Brooklyn

• • •

In 1972, one of the most paradigmatic performers of the Nouvelle Vague wrote, directed, and costarred in a little-known, rarely screened film that we can today appreciate as a worthy entry in the post–New Wave, post–May ’68 canon. Anna Karina’s Vivre ensemble (Living Together), the first of two movies she would helm, premiered in the Critics’ Week program at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973, six years after she had last collaborated with Jean-Luc Godard, the colossus to whom she will forever be linked. From 1961 (the year they wed) to 1967 (two years after they divorced), she starred in seven features and one short from his fertile early period.

Anna Karina as Julie Andersen in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

Although she continued to act with internationally acclaimed directors like Luchino Visconti and George Cukor in the years immediately after her partnership with JLG ended, by the 1970s Karina (who died in 2019, at age seventy-nine) was eager for new challenges. “I just wanted to see if I could do it, that’s all,” she told an interviewer in 2016 about the impetus behind Vivre ensemble—the title of which might be thought of as a riff on that of her second movie with Godard, 1962’s Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live).

Michel Lancelot as Alain Rivent and Anna Karina as Julie Andersen in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

Shot on a minuscule budget in Paris and New York, Vivre ensemble tracks the fractious relationship between Alain (Michel Lancelot, a journalist who, like many in the cast, makes his sole big-screen appearance here) and Julie (Karina), two seemingly polar opposites. He is a besuited secondary-school history professor living with his wife in dull bourgeois comfort and respectability; a typical high point of his workday is lunching in silence at a bistro with a colleague as they both leaf through Le Monde. She is an actress (and perhaps a part-time sex worker), beholden to no one person or schedule. She resides in a disheveled garret in the Latin Quarter that’s festooned with James Brown records, posters of the Marx Brothers and Buster Keaton, and, above her bed, a shrine-like collage of photos of handsome men of many races, whom she identifies to Alain simply as her “buddies.” When they meet by chance at a sidewalk café, it’s coup de foudre. For the spectator long familiar with her work with Godard, this initial encounter provides an opportunity to renew appreciation for Karina, shot in tight close-up during the opening-credits sequence, the radiance of her enormous eyes and mile-wide smile undimmed from a decade earlier.

Michel Lancelot as Alain Rivent and Anna Karina as Julie Andersen in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

Soon Alain is chucking his blazers and ties for all-denim ensembles, bidding adieu to the lycée—his spouse has bid adieu to him—and installing himself permanently in Julie’s flat. If he occasionally rues his declassed status, he benefits from his new girlfriend’s spontaneity, like a spur-of-the-moment trip to New York. The Gotham segment of Vivre ensemble—roughly one-third of its ninety-three minutes—proves the film’s most enchanting, defined by an aleatory quality that likely resulted from the fact that Karina never secured permission to shoot in the city. These scenes are rich with strange, endearing details, like the white rabbit that Johnny (Lynn Berkley)—a strawberry-blond folkie and a member of Julie’s vast he-harem—has with him at all times during his outings with the couple, whether on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum, while cycling in Central Park, or during an impromptu performance on a rooftop with a spectacular view of the Hudson.

Anna Karina as Julie Andersen (center left) and Lynn Berkley as Johnny (center right) in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

Filming surreptitiously, Karina and cinematographer Claude Agostini remain ever alert to possibilities; at times Vivre ensemble becomes a stealth documentary, capturing a sextet of women engaged in anti–Vietnam War guerrilla theater near one of the Central Park transverses. (This episode is a tart, if perhaps unintentional, rejoinder to the “Vietnam War play” scene in Godard’s Pierrot le fou from ’65, featuring Karina smeared in garish yellowface, wearing a conical hat, and speaking gibberish.) The film also introduced me, a New Yorker since 1996, to a location I had never heard of: Staple Street, a two-block stretch in Tribeca where the penurious Parisians split a hot dog.

Anna Karina as Julie Andersen and Michel Lancelot as Alain Rivent in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

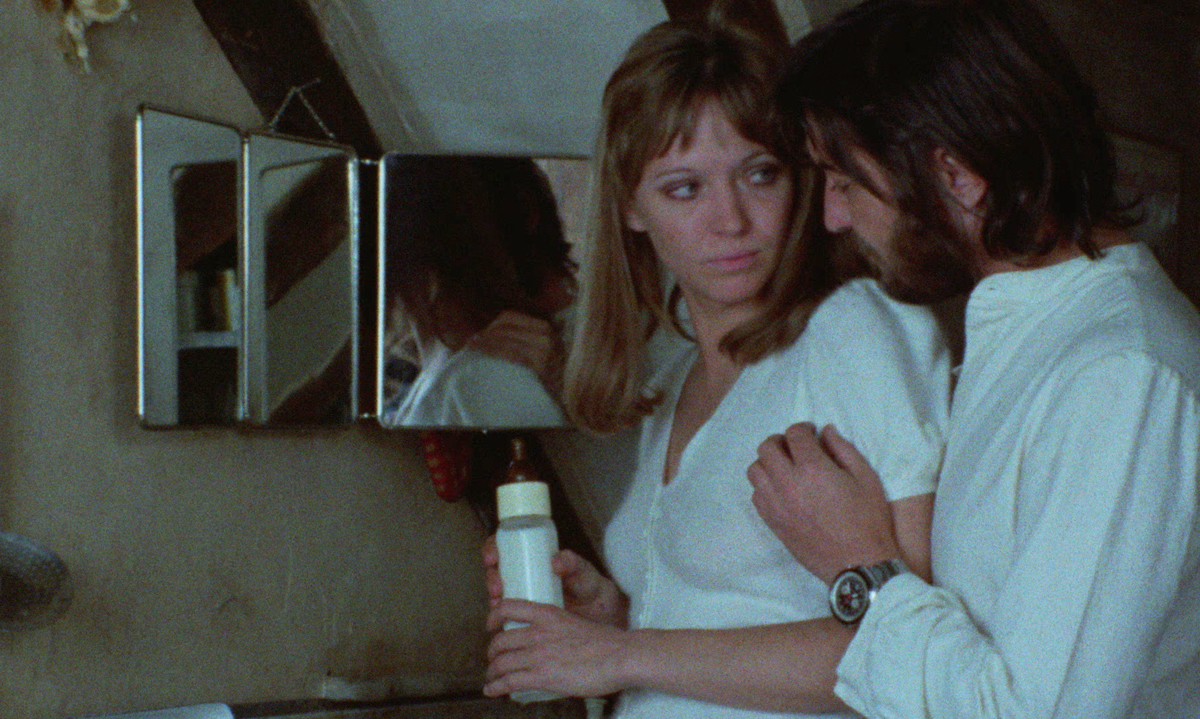

Back in the French capital, Alain’s dissipation deepens, as does the misery of the couple, who soon welcome a baby boy (in a nod to one of the more famous films by JLG’s New Wave confrère François Truffaut, he calls their son “Jules,” while she insists his name is “Jim”). Now bearded and shaggy-haired, Alain is never without a bottle of Gilbey’s whiskey in his hand, slugging down booze during the shambolic private lessons he offers to three unfortunate lads—sessions occasionally interrupted by his drug-peddling. Julie, conversely, embraces responsibility, taking a steady gig as a vendeuse at an antiques shop. (Curiously, once she starts clocking in and out, her hairstyle changes from Klute-era shag to a version of the chic-gamine locks Karina sported in her films with Godard.) They fight, he strikes her (not for the first time), he leaves.

Michel Lancelot as Alain Rivent (left) in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

Vivre ensemble was not critically embraced. In her Cannes dispatch for the Village Voice, Molly Haskell wrote, “The film wallows in a Relationship in that oppressive way that is a woman’s sensibility at its worst.” While I don’t entirely disagree with that assessment, especially as it applies to the movie’s desultory final third, I find it much more rewarding to think of Karina’s directorial debut as a kind of gender inverse of another film that premiered at Cannes in ’73: Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore. Like Vivre ensemble, that movie also stars a Nouvelle Vague icon, Jean-Pierre Léaud, as Alexandre, a Parisian dandy (and a clear stand-in for Eustache) in a tumultuous open relationship with a slightly older woman who financially supports him and a nurse devoted to libertinism. Both films showcase attic apartments as key settings, with a particular focus on what happens in and out of the beds that dominate each flat.

Anna Karina as Julie Andersen in Vivre ensemble. © Malavida.

A voluble post-’68 dirge, The Mother and the Whore looks askance at the cultural revolution; to Alexandre’s disparaging mention of “women’s lib,” his nurse lover replies, “What’s that?” Although punctuated by bleak moments, Karina’s film, in contrast, maintains an odd kind of buoyancy. While Vivre ensemble also reflects the seismic changes wrought by the upheavals of soixante-huit, we are certain that Julie can navigate them successfully—unlike Alexandre, a coddled coxcomb sure to drown in his own torrent of bilious words. For Julie, living together is only one option. It’s her life to live.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.