George Baker

George Baker

Moments of wonder: the Norton Simon Museum dives into the art of ardent collector Galka Scheyer.

Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California, installation view. Image © Norton Simon Art Foundation.

Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California, Norton Simon Museum, 411 West Colorado Boulevard, Pasadena, CA, through September 25, 2017

• • •

I was wandering the halls at UCLA when my now-departed colleague, Al Boime, took me aside to commiserate, sharing with a young Dada scholar how UCLA almost became the resting place of most of Marcel Duchamp’s work. I had no idea: the Walter and Louise Arensberg Collection was deeded to UCLA in 1944, along with the collection of Galka Scheyer, their sometimes friend and sometimes dealer, after her death in 1945. The stipulation was that UCLA had to build a suitable museum, and, for the Scheyer collection, publish a catalog. The fledgling institution failed in both regards, and all the Arensberg Duchamps and Brancusis floated away to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Scheyer’s bequest of almost five hundred artworks stayed in California, landing eventually at what is now the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California is by no means the first time the museum has created a didactic exhibition from the collection, but Scheyer’s story remains under-known. Born Emilie Esther Scheyer in Braunschweig, Germany, in 1889, she abandoned her own ambition to be a painter after a revelatory encounter with the expressionist work of Russian artist Alexei Jawlensky. Seeking him out, Scheyer devoted herself to Jawlensky’s cause, as she would later to his lifelong friend Wassily Kandinsky, and two other artist-teachers working alongside Kandinsky at the Bauhaus after World War I: Lyonel Feininger and Paul Klee. She proposed an association—not exactly a movement, more a kind of “brand”—christening the group the “Blue Four,” and she in turn was baptized by Jawlensky after an image in a dream as “Galka,” the Russian word for a blackbird or a type of crow.

Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California, installation view (Kandinsky wall). Image © Norton Simon Art Foundation.

Acting as both ardent collector and agent, Scheyer set out in 1924 to promote the work of the Blue Four in the United States, settling in San Francisco by 1925. But “settling” is the wrong word: the move to bring German modernist painting to California was audacious, and Scheyer shuttled endlessly up and down the West Coast. She organized exhibitions, lectured tirelessly, taught art and modernism to children, sold works by her “Blue Kings” to businessmen and Hollywood types, to John Cage, to the Arensbergs. But her interests extended beyond these four painters. She arranged an exhibition of constructivist drawings and posters at the UCLA campus as early as 1927. She associated with other modernist émigrés, coming to know the Austrian-born architect R.M. Schindler, for example, living for a time in the close quarters of his Kings Road House (and briefly falling in love). She tangled with the California bohemians like Edward Weston, with whom upon first meeting she traded clothes at a raucous party (she “begged my leather breeches,” Weston wrote in his Daybook in 1927, “so I got in exchange her outfit even down to [her] panties, and a marvellous make-up job to boot”). By 1933, Richard Neutra designed her a home in the Hollywood Hills dubbed the “Blue Heights,” where her collection and activities could finally be centered.

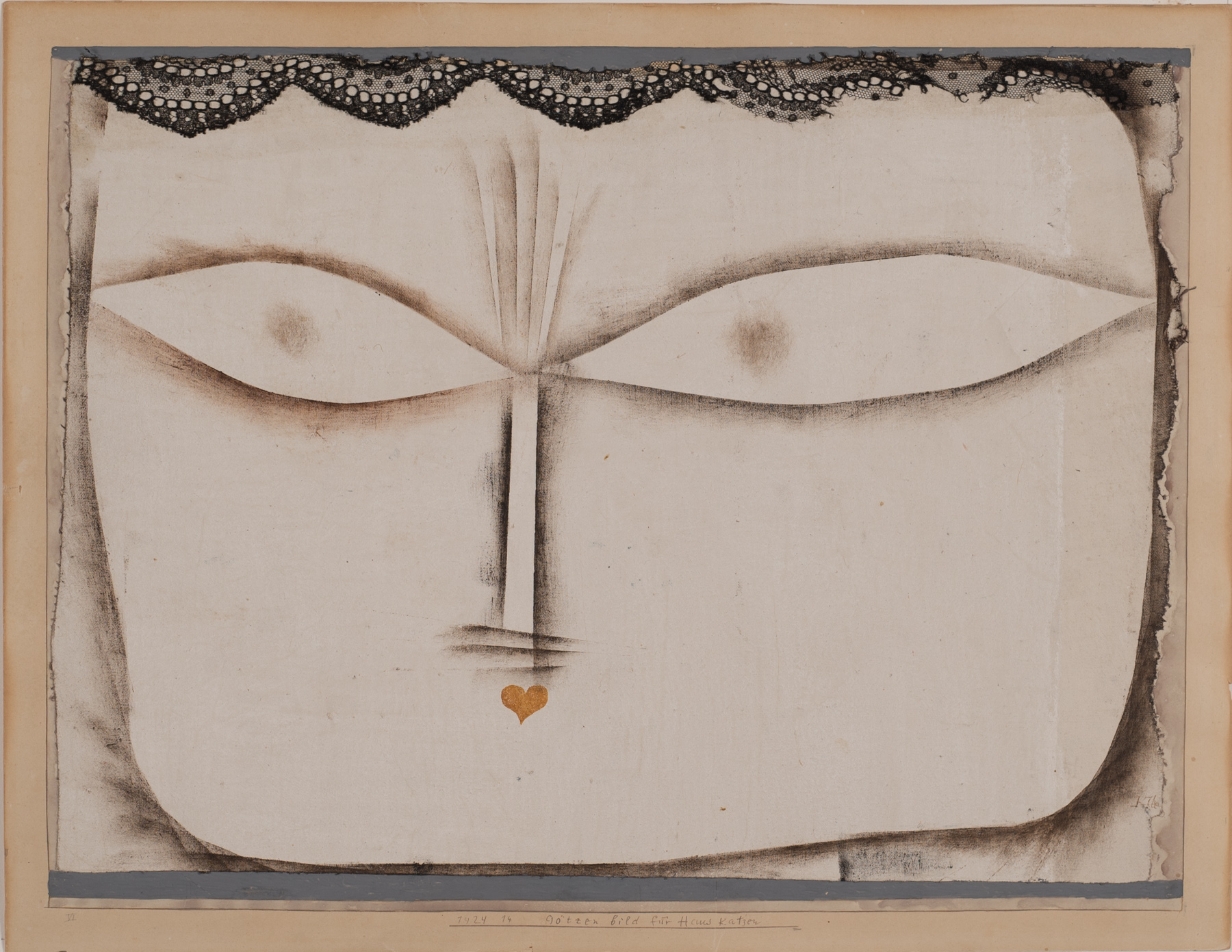

Paul Klee, Idol for House Cats, 1924. Watercolor, oil transfer drawing, and lace collage on chalk-primed muslin, mounted on thin cardboard, 13 ⅞ × 18 ¼ inches. Image © Norton Simon Museum.

Maven of Modernism contains an extraordinary scarlet Klee from 1918, The Tree of Houses, painted in part on gauze, like a blood-soaked bandage. Resembling, too, a miniature tapestry, Klee’s image underlines the feeling one gets in the Scheyer collection of being surrounded by modernism as it was lived in the space of a home, filled with the intensities of affect and personal significance. Many of the works were originally gifts from the artists to Scheyer, and they are inscribed like endless love letters, to our “Little Friend,” to “dear Galka-Emmy.” Indeed, one can simply wander through the exhibition as a collection of idiosyncrasies, of modernism as eccentricity, so many individual moments of wonder: another Klee, Idol for House Cats, 1924, with a real piece of lace attached like a Spanish mantilla to the painted constructivist face of the artist’s beloved cat Fritzi; no less than three diminutive Merz collages by Kurt Schwitters, the rubbish scintillating with chocolate wrappers and the decaying image of two red hearts; a Lissitzky Proun (there are many) with its primary geometries cut out of the work’s surface, like a stencil for the eyes; the many works by children, by Klee’s son Felix, or Weston’s son Brett, who as a teenager made his first sale of a photograph to Scheyer, a three-by-three-inch print of a lily, for $2.50.

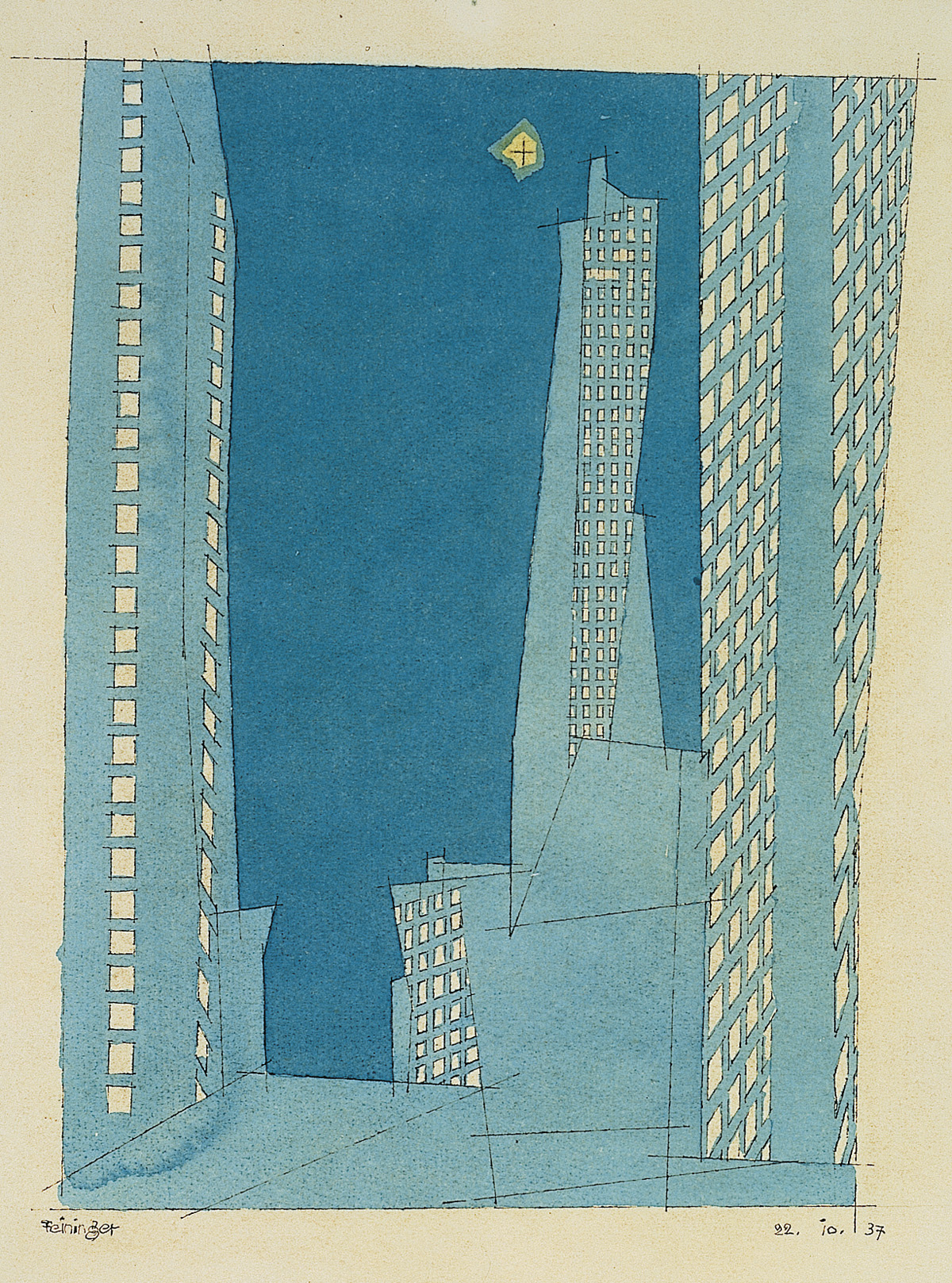

Lyonel Feininger, Blue Skyscrapers, 1937. Watercolor and India ink on laid paper, 10 × 7 ⅛ inches. Image © 2017 Artists Rights Society / VG Bild-Kunst.

There is a consistent thread in the exhibition’s wild inconsistencies, itself peculiar, a through line in the color blue. Scheyer’s name for the Blue Four clearly harks back to Kandinsky and Jawlensky’s prewar expressionist Blue Rider Group. But blue appears everywhere in the works that Scheyer owned, from Klee’s watery Aquarium Green-Red, 1921, which is anything but green and red, to Kandinsky’s popular lithograph Blue, 1922, or Feininger’s watercolors like Blue Skyscrapers, 1937 or Blue Shore, c. 1938. This is more than expressionist “free” color: the blue instead evokes the excessive and obsessional. Scheyer named one of her dogs “Blue Blue.” In Mexico, acquiring a work by Diego Rivera, she made sure it too was blue, a painting entitled Blue Boy with the Banana, 1931.

Diego Rivera, Blue Boy with the Banana, 1931. Oil on canvas, 36 × 21 ⅝ inches. Image © 2017 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust / Artists Rights Society.

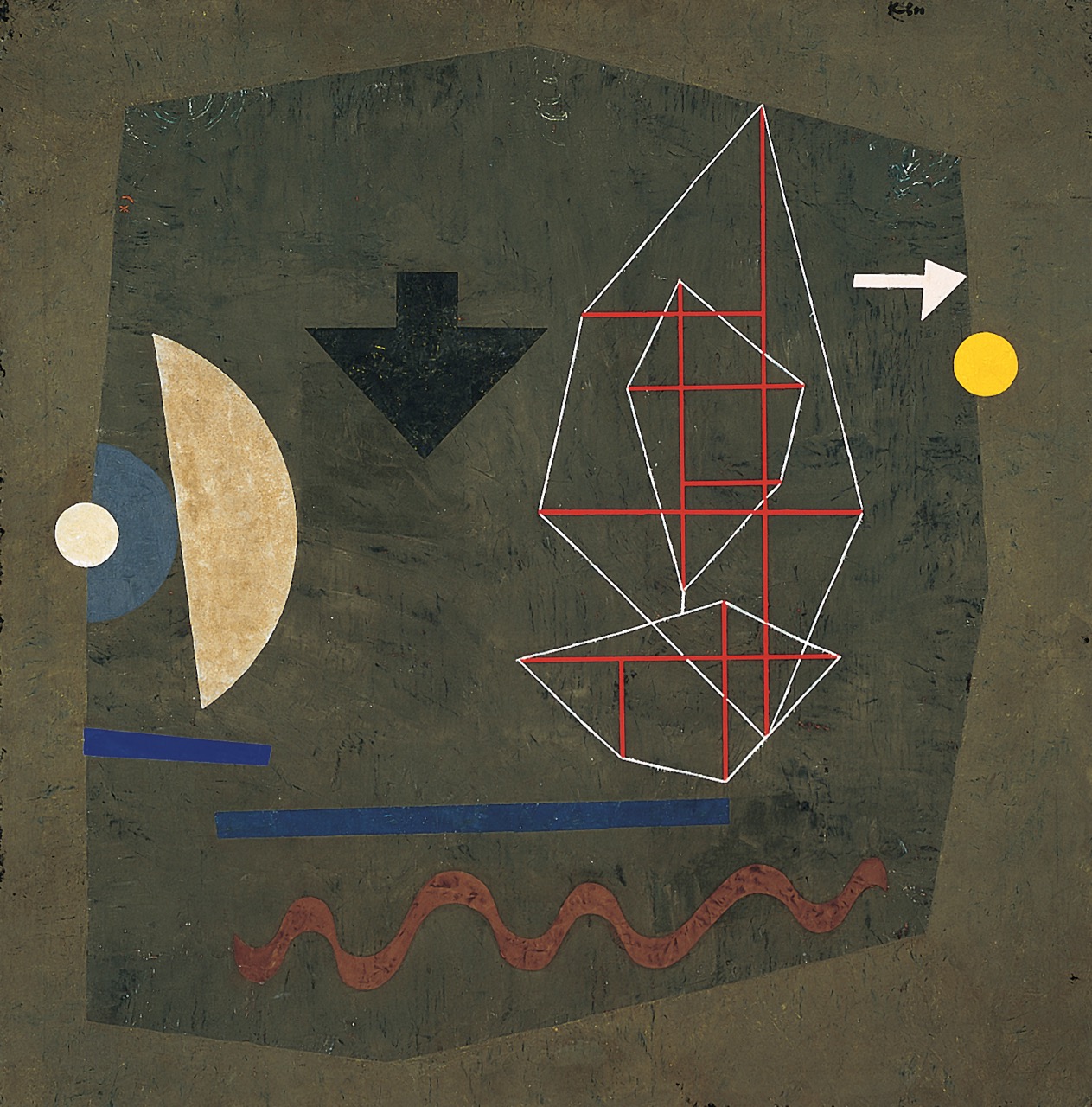

While not explicit in the show’s curation, an aesthetic with gendered, perhaps even feminist implication emerges. Like the example of Katherine Dreier and her prescient museum baptized the “Société Anonyme,” we face a form of modernism mediated through the organizing actions of a woman. Blue has come to be gendered male, but in the Scheyer collection, it erupts in myriad liquid metaphors and techniques: the focus on modest watercolors; the unbounded color puddles characteristic of Jawlensky’s manner of painting; the nautical world called up by the quivering, paradoxically borderless line of Feininger’s many images of ragged drifting ships, or Kandinsky’s biblical floods, or the signal work by Klee, Possibilities at Sea, 1932, made from hot wax and sand. Scheyer described the Klee painting “as unfathomable as the ocean’s pulse,” with its diagrammatic sailboat on a “sea” of two blue lines, a worm-like wave form, contradictory arrows and cosmic spheres—a constructivist rival to the best surrealist Miró, modernist form as all fluidity and flow.

Paul Klee, Possibilities at Sea, 1932. Encaustic and sand on canvas, 38 ¼ × 37 ⅝ inches. Image © Norton Simon Museum.

The lesson of the show might be that this potentially gendered aesthetic can be followed into the actual modernisms that Scheyer’s advocacy influenced in California—which would ultimately lie not in expressionist-type painting but in the more expansive and spreading constructivist forms of architecture, photography, music, film. Maven of Modernism contains many works by the photographers of the Group f/64, Imogen Cunningham’s throbbing hothouse flowers, Weston’s precision photographs made in the face of seashells and teeming seaweed, or the rippling Oceano dunes (a site, near Pismo Beach, to which Scheyer introduced him). There is at least one wobbling drawing by the architect Schindler, Trickling Hands, 1914–17, poetically inscribed: “Throttling fist – Faltering death – Trickling hands – Fluid life.” There is one of the most beautiful photographs you will ever see, of Scheyer posing in her Neutra house with a dog, reflected in the glass frame of a nearby watercolor, the entire architecture glistening with California light. In the background, Maya Deren appears through the slit of an exterior window, like a younger ghost of Scheyer herself, a visual rhyme created by the two women’s extraordinary wave-like hair. Taken by filmmaker Alexander Hammid, the photograph is hard-edged and yet boundless, an image of pure reverberation. And so, one wants to say, was Scheyer’s modernism.

George Baker is a co-editor of October magazine, and a frequent critic for publications including Artforum, Aperture, Texte zur Kunst, and frieze. He is completing a book on contemporary photography, entitled Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography, and has recently worked closely with artists Paul Chan and Walead Beshty on their respective books of collected writings. He teaches modern and contemporary art at UCLA.