Erika Balsom

Erika Balsom

A wide-ranging retrospective spotlights a shapeshifting filmmaker typically celebrated for his work with onetime spouse Maya Deren.

Still from We Are Young! Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

“Alexander Hammid,” Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, New York City, through January 29, 2023

• • •

Margarida Cordeiro, Danièle Huillet, Anne-Marie Miéville: how often it is that the female half of a filmmaking couple receives less attention than her male partner. A true reversal is found in Alexander Hammid, né Hackenschmied. Born in Linz in 1907, he is typically mentioned in the same breath as the emphatically more celebrated Maya Deren, his spouse from 1942 to 1947, with whom he created Meshes of the Afternoon (1943). Who was Hammid beyond this lionized short, one that film historian David E. James has called “the single most consequential film in the American avant-garde and hence one of the pivotal achievements in the history of cinema”? A wide-ranging retrospective at Anthology Film Archives provides an opportunity to find out, surveying Hammid’s diverse pursuits across forty-six years and multiple genres, from early work in the Czechoslovak Republic through his engagement with 70mm and multiscreen formats in the 1960s and 1970s.

Still from Aimless Walk. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

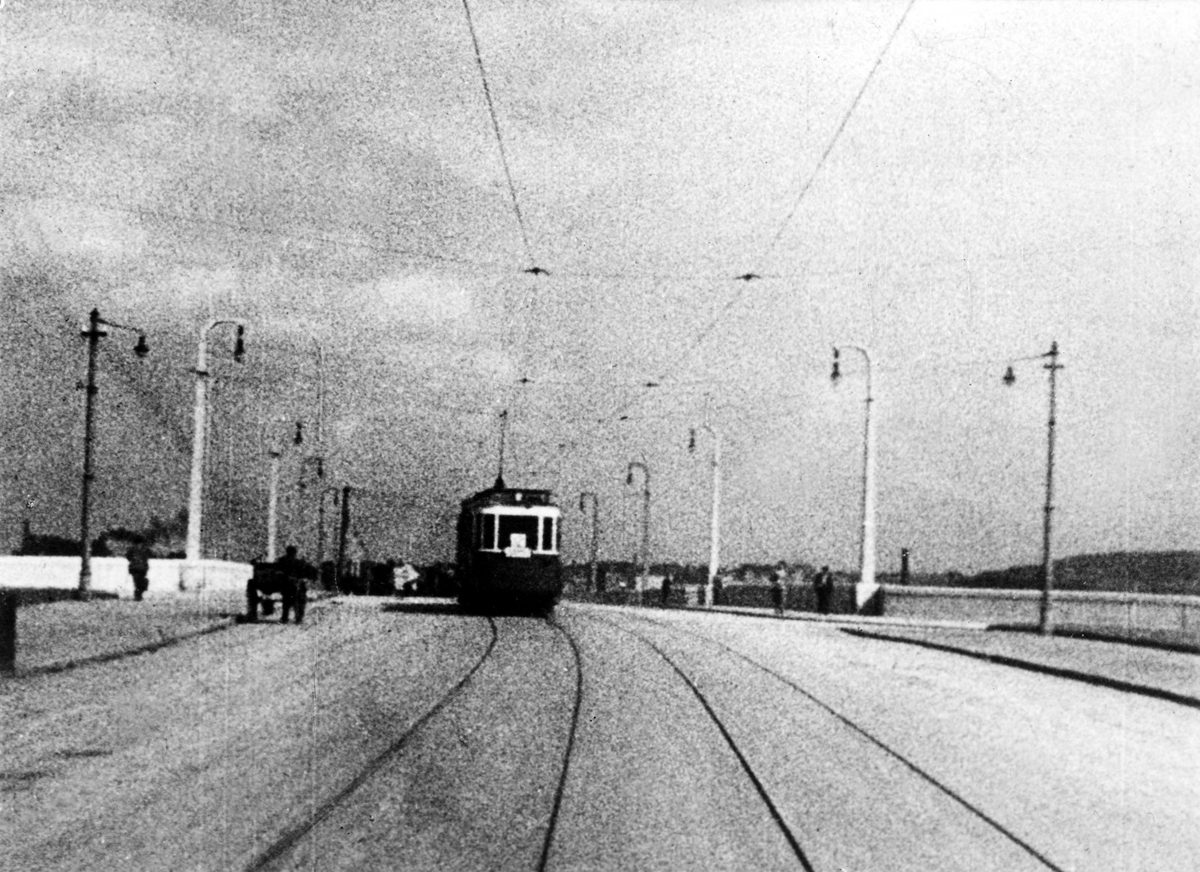

Hammid was active in interwar Prague as a photographer, filmmaker, writer, and curator, making his first foray into directing with Aimless Walk (1930). Initially, the eight-minute film appears to be a city symphony celebrating the speed of the modern metropolis, combining views from a moving tram in a dynamic montage that emphasizes the graphic tension of diagonal lines. Quickly, however, departures from the genre become clear. A protagonist appears, a man who is escaping from the urban core into the languor of the periphery. The tempo slows; architectural elements are reflected in water as unstable, wavering forms, offering a visual metaphor for the loosening of life’s strictures. The film concludes with a surrealist touch, as its central figure splinters into two, with one incarnation staying behind at river’s edge, watching the other as he returns to the demands of the city.

Still from Aimless Walk. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

The use of the doppelgänger motif in Aimless Walk is auteurist catnip, seemingly a clear prefiguration of the psychodramatic multiplication of Meshes thirteen years later. And perhaps it is—but good luck trying to extend this line of thinking much farther into Hammid’s corpus. Unlike Deren, who possessed an indelible signature and whose films are inseparable from her sorcerous persona, he was a shapeshifter, an anti-auteur who receded into his collaborations with others, fully deserving of the headline that graced his 2004 New York Times obituary: “filmmaker known for many styles.” What emerges from a holistic look at his career is not the consistent articulation of a singular vision, that thing so dear to film criticism, and perhaps nowhere more so than in avant-garde circles. His peripatetic arc tells a different tale, one of a film worker who connects experimental, educational, promotional, and sponsored forms of cinema.

Still from Crisis: A Film of the Nazi Way. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

During the Second World War, Hammid put his skills to partisan use, collaborating with antifascist documentarian Herbert Kline on two films, including Crisis: A Film of the Nazi Way (1939), which explores the fate of the Czechoslovak Republic with a focus on the German-speaking region of the Sudetenland. The end of this stentorian piece of agitprop finds the country betrayed by its democratic allies, pushing streams of refugees into exile. Hammid himself would be one of them; in early 1939, he left for Paris and by the end of the year arrived in New York. The Anthology retrospective focuses overwhelmingly on the American period that followed—perhaps an understandable decision, but a missed opportunity to present more of Hammid’s Czech work, like Gustav Machatý’s fascinating Erotikon (1929), on which he served as art director.

In the US, Hackenschmied became Hammid, a renaming he described as motivated principally by convenience but also as a way of dispensing with any echo of Hakenkreuz, German for “swastika.” Unable to find employment in Hollywood without union membership, he made his way on the sidelines of the industry, working across idioms. In Mexico, he and Kline codirected The Forgotten Village (1941), a film populated by nonprofessionals, based on a story of typhoid infection by John Steinbeck. Narrated by Burgess Meredith in a mannered voice-over at odds with the naturalism of Hammid’s images, it drips with settler-colonial ideology, rationalizing intervention in Indigenous communities by pitting lifesaving science against traditional healing.

Still from Private Life of a Cat. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

During his partnership with Deren—which also resulted in the unmissable Private Life of a Cat (1946), featuring the couple’s pet Glamour Girl as she gives birth to and raises kittens—Hammid elsewhere deployed an altogether different cinematographic language, making propaganda films for the Office of War Information. Soon after, he directed squeaky clean social guidance films like Who’s Boss (1950) and It Takes All Kinds (1950). Part of a series based on Henry A. Bowman’s 1942 book Marriage for Moderns, these shorts attempt to lubricate the postwar renegotiation of gender roles, instructing viewers on matters of heterosexual compromise and compatibility. “When you marry, you must live with a person, not a dream,” the voice-over counsels, offering a pragmatic vision of conjugal life that could not be more distant from the oneiric vagaries of Meshes.

Still from Who’s Boss. Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

In 1962, Hammid joined forces with Francis Thompson, delivering the triple-screen epic To Be Alive! (1964) for the S. C. Johnson & Son Wax pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, where it drew some five million viewers. Shot in the US, Italy, and Nigeria using three 35mm cameras simultaneously, this Academy Award–winning attraction is a humanist spectacle at grand scale, preaching the universality of experience across cultures and revelling in the sheer joy of existence. As suggested by their consistently exclamatory titles—e.g., To the Fair! (1964), We are Young! (1967)—Hammid and Thompson’s films are full of thrill and wonder. They brim with a Cold War optimism in which the psyche-splitting ambivalence of Aimless Walk has no place and only progress lies ahead. Even an otherwise breathless Times review of To Fly! (1976), on which Hammid was supervising editor, takes note of the nationalist fantasy that pervades this early IMAX film: amid all its awesome aerial views, “somebody has done a great job of editing out the deteriorations of which we are daily more conscious at ground level.”

Still from To the Fair! Courtesy Anthology Film Archives.

In a 1930 article, Hammid emphasized the affinities between forms of filmmaking beyond the fiction feature, asking, “Why place the attempt at pure art film somewhere other than with the superb science film, the superb travel film, or the superb propaganda film?” In many histories of cinema, these have remained separate from one another. Now, as scholars increasingly explore their interconnectedness, Hammid’s trajectory is undoubtedly relevant. Nevertheless, there is some merit in considering the art film at a remove—as his heterogeneous filmography demonstrates, the imprint of subjectivity and the contestation of dominant norms are far less likely to be found outside its precinct.

Erika Balsom is a Reader in Film Studies at King’s College London. Most recently, she is the coeditor of Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image, published by MIT Press.