Eric Banks

Eric Banks

Stalin speaking: Ismail Kadare’s new novel circles relentlessly around a real-life phone call involving the Soviet leader and two famed writers.

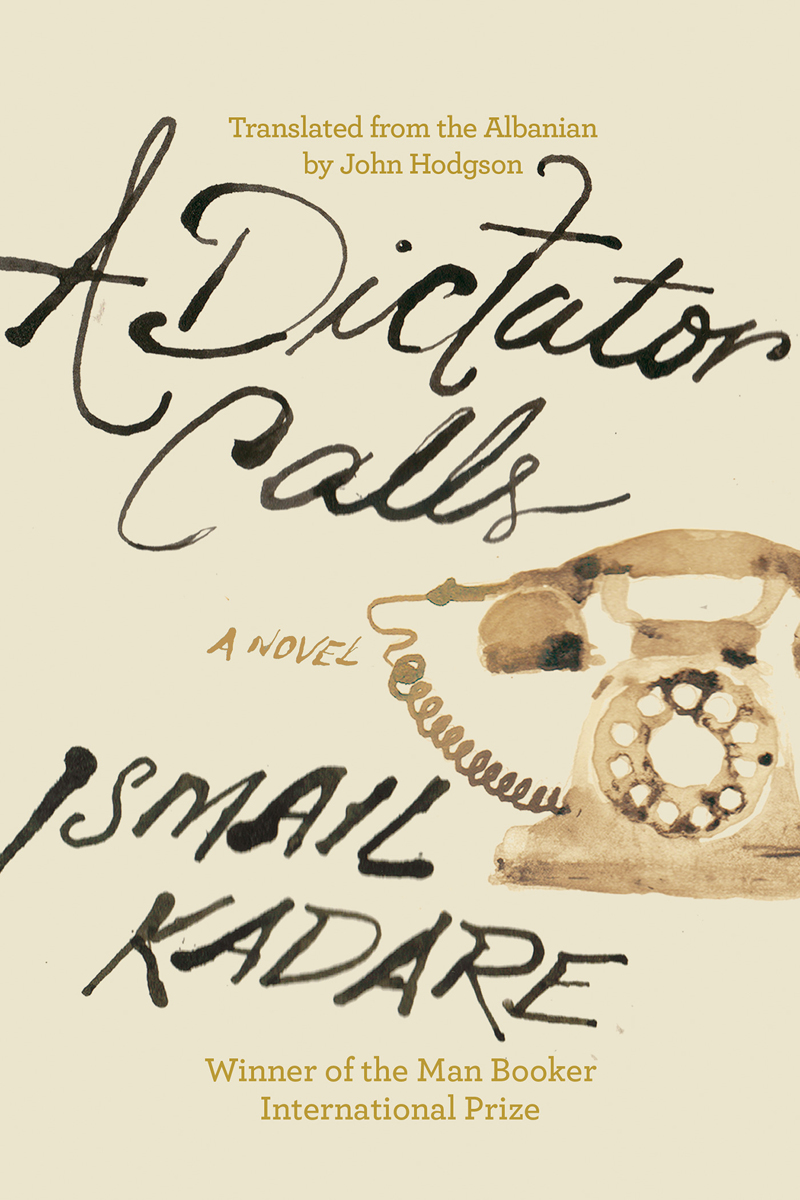

A Dictator Calls, by Ismail Kadare, translated by John Hodgson, Counterpoint, 230 pages, $16.95

• • •

The phone call lasts three to four minutes. It’s placed by a tyrant (Joseph Stalin) to a writer (Boris Pasternak), about a third writer (Osip Mandelstam), who has been arrested, possibly for the insulting lines contained in his “Stalin Epigram,” aka “The Kremlin Mountaineer,” which some will (dubiously? strategically?) distinguish in the moment as more satire than poetry and which has occasioned (and will occasion) the ongoing intercession of various Soviet writers on behalf of Mandelstam, who would, four years later, die in internal exile, in 1938. During the call, Pasternak is addled and fumbling; Stalin grows annoyed and, dissatisfied with the writer’s answers, hangs up. A strange episode, the content of which remains malleable, from teller to teller, and the point of which remains a riddle. “Why did Stalin telephone and why was Pasternak confused?” Ismail Kadare asks in A Dictator Calls. “The arrest of a great poet might come as a shock in London or Paris, but not in Moscow in 1934.” (Or Tirana, for that matter, during the Albanian writer’s most formative years.) “What did the poet and the tyrant expect of one another, were they hiding something and were they both afraid of what they were hiding?”

The fabled call is the sort of enigma that has long drawn Kadare’s attention, and here he is in true form, devoting a massive chunk of its pages to what he sees as the ineluctable mysteries of Pasternak’s encounter with tragic fate, the perplexing presence of Stalin, and the long shadow of Mandelstam and what has famously been called his sixteen-line death sentence. At age eighty-seven, Kadare is among the last survivors of the generation of writers from the Other Europe, as it was dubbed by Philip Roth’s 1970s series introducing a number of now-canonical Iron Curtain novelists. Roth’s series didn’t include Kadare; Enver Hoxha’s inscrutably paranoid Albania was practically Other Europe’s Other Europe, and the Tirana-to-Paris route taken by Kadare’s manuscripts in the ’70s and ’80s to the West involved unique circumstances—his smuggled texts were translated and at times published without his knowledge. Their Albanian provenance, in all its political, linguistic, and historical specificity, and the often-peculiar hiccup in time between publication and translation have left their own mythical mark on the author’s identity.

The slim new book A Dictator Calls, translated by John Hodgson, is indeed new, but in many ways it’s a footnote to another of Kadare’s works that may have looked new when it appeared in English in 2014 but had actually been published in Albania more than four decades earlier, Twilight of the Eastern Gods. Originally part of a loose trilogy, Twilight is a bleak recounting of the author’s frosty apprenticeship in Moscow, at the Gorky Institute for World Literature, a portrait of the artist as a young man studying alongside the dullest of dull young things as Socialist Realist diktat chilled the horizon of possibility for his classmates. It unwinds in 1958 as Albania begins to break with the Soviet Union and embark on its postwar destiny as a Hermit Kingdom on Balkan soil. Kadare captures the spirit of literature’s relation to state power in that autumn’s terrifying public campaign against Pasternak, launched after he was named winner of the Nobel Prize. Censored in the USSR but published internationally (possibly thanks to some subterfuge by Isaiah Berlin) to acclaim, Doctor Zhivago secured the award for Pasternak but earned him the enmity of the state. Faced with the choice of exile or declining the honor, he opted for the latter and died a broken man soon after. In A Dictator Calls, Kadare describes him as the first writer to be killed by the Nobel Prize.

“I . . . might be on that list,” Kadare writes in the darkly comical opening section. What list? For the Nobel? For execution? A Dictator Calls proposes that both options are simultaneously possible. The book begins circa 1976 by recursively reenacting the faceless vetting of his Moscow manuscript. Was his account of hack writers and Moscow goons in the ’50s an oblique critique of Hoxha and Tirana? Of course it was, but its ambitions were not so single-minded. The Kadare character sweats his squeamish editor’s response, which grows more and more worrisome (“Pasternak was no angel” is typical of the feedback), yet the book somehow quickly escapes the censor’s grasp and is published. Picking up a copy from the printer, Kadare remarks that the prosecutors had been fast this time. “What prosecutors?” his editor replies puzzlingly. “The prosecutors will look at it now that it’s published.”

Persecution is an odd dance. Pasternak 1976, Pasternak 1958, Pasternak 1934, the “intoxication of downfall”: the personae circle each other in A Dictator Calls—Pasternak, Mandelstam, Stalin, Hoxha, Kadare, not to mention the rivals and intimates who have added their own accounts of the telephone anecdote to the archive over time (there are thirteen on display here; Kadare confesses he is an obsessive collector), from Viktor Shklovsky to Anna Akhmatova and Isaiah Berlin. There are some minor differences in how they report the story, with occasionally large discrepancies: in one, Pasternak tries to ring Stalin back but is told the telephone number had been created exclusively for one single call—Stalin’s to Pasternak—and no longer works. In another, Pasternak expresses his desire to talk to Stalin about history and poetry, triggering the dictator’s angry reaction. In a few reports, the writer comes off as hopelessly naïve, in some, dangerous and reckless, in most, the hapless victim of a historical trap. Like similar encounters Kadare assays of the poet and prince—Alexander and Pushkin, Lenin and Gorky, Stalin and Sholokhov, who, as his biographer put it, “impersonated a great writer long enough to become one”—the question of who deploys the power they wield, and why, isn’t always clear.

Kadare’s relentless examination of the anecdote makes it oddly less resolved by the end of A Dictator Calls than it seemed at the outset, like a literary Rubik’s Cube he has turned over and over without making much progress. If anything, I suspect the reader’s sympathies will migrate to Pasternak, “the distinguished writer, unloved by this state and its leader.” Was a different response to Stalin during those three or four minutes even possible? When Kadare relates a recurring dream in which he himself gets a call from a dictator, with Hoxha on the other line, the Albanian Stalinist showers him with compliments. The only response Kadare can muster is a flustered “Thank you, thank you.”

Eric Banks is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities at the NYPL. He is the former president of the National Book Critics Circle. He was previously editor-in-chief of Bookforum and a senior editor at Artforum.