Carlos Basualdo

Carlos Basualdo

The poet, the political scientist, the historian, the curator,

the cosmopolitan Africanist.

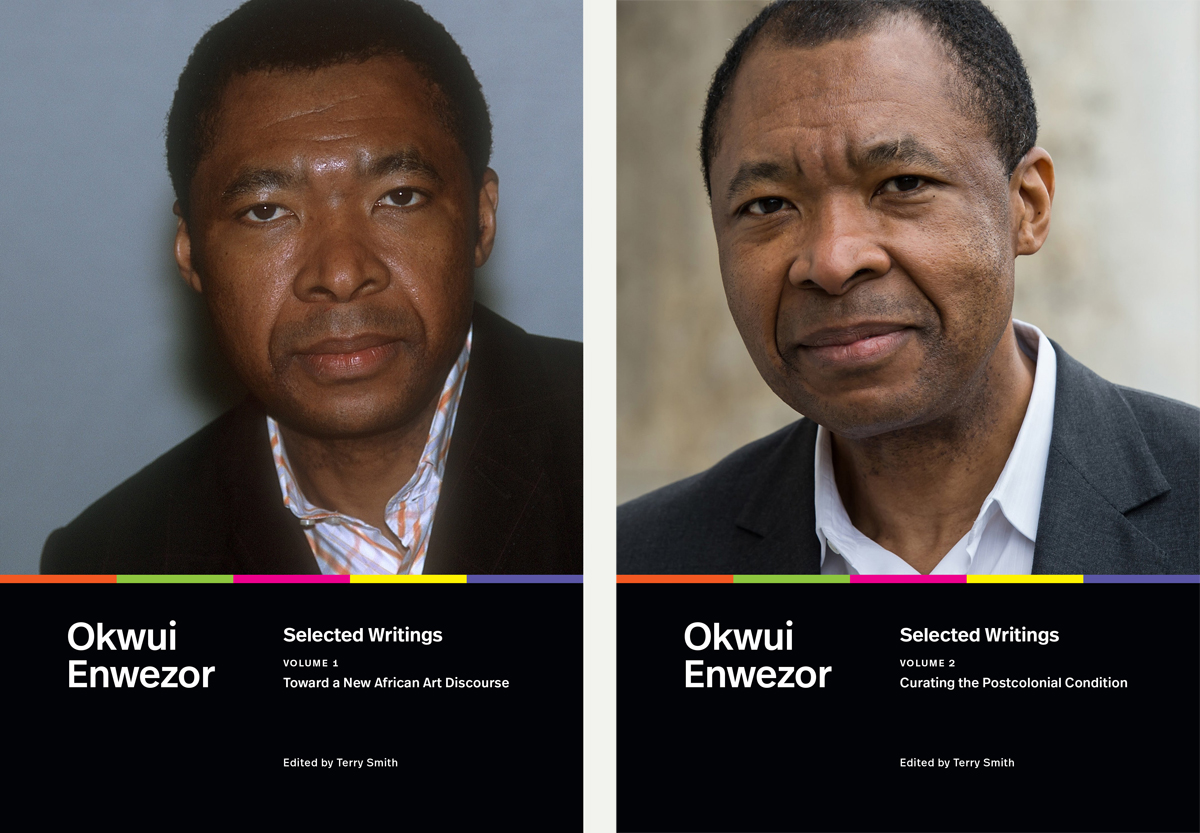

Okwui Enwezor: Selected Writings, Volume 1: Toward a New African Art Discourse and Volume 2: Curating the Postcolonial Condition, edited by Terry Smith, Duke University Press, 444 pages and

528 pages respectively, $40 each

• • •

Right at the start of Okwui Enwezor’s Selected Writings, edited by Terry Smith, readers are introduced to its main characters—characters always engaged in a continuous movement of intersection and mutual redefinition. They include the historian, deeply involved and committed to a work of healing and reparation; the poet, with his profound sensibility for individual artworks and his care for literary form and rhetoric; and the political scientist, utterly committed to a clearheaded analysis of the conditions of production that determine and enable a certain status quo in contemporary art. More than presenting a solitary voice emanating from a discrete subject, Enwezor’s essays are endowed with a choral quality, thus questioning the very possibility of identifying a singular and unchanging position as their unified source.

The inaugural tract is “Redrawing the Boundaries: Toward a New African Discourse,” published in 1994 as the editorial statement for the first issue of Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, the magazine that Enwezor cofounded with Salah Hassan and Chika Okeke-Agulu. It delineates the clearly ambitious scope of the author’s intellectual project: to demonstrate that the African continent, far from being an empty screen for the phantasmatic—and most often brutally violent—projections of the colonial West, is full to the brim with a multiplicity of histories and cultures. Enwezor insistently refuses to define Africa and its people negatively, as somebody else’s “other.” Instead, his work constitutes a vitalist affirmation of present and future possibilities for the continent and its contemporary artists and art. Throughout these pages, the political scientist returns time and again to better specify the task at hand and locate it firmly within the context of the transformations of the world system in the second half of the twentieth century. The poet is charged with keeping the connection between art and discourse vibrant and alive, while reminding the reader of what ultimately constitutes the raison d’être of these texts—a historical interpretation of art in the here and now.

Enwezor’s relationship to the abysmal trauma of colonialism lies at the core of his work. The term means something very specific in the context of his writings: the process of partition and domination of the African continent that the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 both sanctioned and exacerbated. It was then that the European powers, in a delirious act of arrogance and self-deception—and in blatant absence of any representative from the African nations—carved up the continent along artificial colonial lines. Anti-colonialism permeates Enwezor’s project as an existential opposition to a will to power that consists exclusively of annihilation, the obliteration of history, and the expropriation of bodies, objects, and territories. For Enwezor, the colonial endeavor is the pure manifestation of that negativity he ceaselessly opposes, the original scene against which the tragedy of modernity unfolds. This perhaps accounts for the profound ambiguity that Enwezor expresses in these essays toward modernity (and modernism in the arts). On the one hand, modernity is the very vehicle of colonialism, its rationale and motivation; on the other, it is the horizon of hope against which African anti-colonial fighters articulated the national liberation projects in the decades after the Second World War. Enwezor never fully abandoned the hope that modernity could—or, better, should—be fully reimagined and utterly reformed. Even though European colonialism in Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries remains the focus of his concerns, Enwezor’s analysis adheres to the narrative that locates the source of the colonial impulse in the aggressive European mercantile expansionism of the sixteenth century, and thus relates it to the development of capitalism and the constitution of a world system. Capitalism would then be equated in this context with the European colonial adventure, and modernity considered its bastardized vehicle for domination at a global scale.

The first volume focuses on pieces originally written in response to the discussions on globalization that dominated the cultural field in the 1990s. Enwezor belonged to a cohort of cultural producers who converged in the urban centers of the West at that time as part of the accelerated movement of commodities, services, and peoples characterizing this moment in late capitalism. Even if fraught with contradictions and perils, globalization was still seen by many non-Western writers of Enwezor’s generation as a possibility—one that could bring attention to the localized histories of art in the twentieth century in a way that would profoundly interrogate the canonical narratives of the West. Enwezor, with lucidity, defines that possibility in one of the most inspiring texts of the first book, “The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition.” In this essay, written in 2003, shortly after the completion of his monumental documenta11 the year before, Enwezor enlists contemporary art in its many variegated and experimental forms as a potential antidote to the rigidities of canonical (Euro-American) modernism. What Enwezor calls “contemporary art” in this context is in fact an alliance of practices that are fundamentally critical of the then status quo. In his own words:

Suffice it to say that my conception of the postcolonial constellation comes out of the recognition made clear by the current upheaval evident in a series of structural, political, and cultural restructurings since after World War II, which include movements of decolonization and the civil rights, feminist, gay/lesbian, and antiracist movements. The postcolonial constellation is the site for the expansion of the definition of what constitutes contemporary culture and its affiliations in other domains of practice, the intersections of historical forces aligned against the hegemonic imperatives of imperial discourse.

Against the background of a systematic critique of Western cultural institutions, which he identifies as privileged vehicles for expressing the forms of domination proper to late capitalism, Enwezor, the poet / historian / political scientist, detects a glimmer of hope in the multiple forms of contemporary art, enabled and amplified by the forces of globalization.

The initial questions still remain: How to define or describe the author of these texts; which position is ultimately articulated in, or by, this collection of essays? Without a hint of doubt, Enwezor, the poet, the political scientist, the historian, is consistently a cosmopolitan Africanist. His version of the continent is that of an ever-changing multiplicity that is never rigidly associated with any forms of racial essentialism—a notion against which he argues explicitly. Equally importantly to keep in mind is that many of these essays were written as prefaces or prologues to art exhibitions, and should be read in that context: the text provides the narrative scaffolding for the project, but is never a substitute for the actual experience of the show. At times, Enwezor assumes the position of the art critic, as in many of the pieces in both volumes dedicated to individual artists. Most often, he is a rigorous art historian, as in the brilliant essays devoted to African photography, including his pioneering “Colonial Imaginary, Tropes of Disruption: History, Culture, and Representation in the Works of African Photographers” from 1996, written with Octavio Zaya as an introduction to the groundbreaking exhibition In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, held at the Guggenheim Museum that year. Almost always, he is a curator, writing with and for the art and artists that he is presenting. Again, no fixed subjective position should be expected from these essays. Instead, we are confronted with a process of becoming: the becoming critic of the poet, the becoming historian of the curator, the becoming poet of the political scientist.

One thing should be made clear: the main reason why there seems to be no fixed authorial position is simply because that prerogative is never fully available—or desirable—to a Third World intellectual, whose work, by necessity, is subjected to the contingencies of time and place. The attempt to articulate a critical position outside the canonical discourses and institutions of the West is both an intellectual project and a way of life. The Third World intellectual is fundamentally—as Enwezor recognized in one of his early essays, “Travel Notes: Living, Working, and Traveling in a Restless World”—an existential traveler, both literally and metaphorically, someone who chooses to use the language and the conceptual tools of the West in order to critique them, to introduce the disruptive violence of a “minor literature” (in the words of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari) inside the language of the colonial masters.

Lastly, the becoming curator of Enwezor implies that his writings should always be considered along with the exhibitions that he curated. Written language here does not occupy a hegemonic position but walks alongside embodied experience, even if this takes the narrative form of a recollection. Enwezor’s work thus articulates a triple challenge to the canonical (Western) narratives of art history: at the discursive level, in terms of subject matter and content; at the level of the relation between discourse and the actual experiential narrative of his exhibitions; and in the strategic fluidity with which Enwezor assumes a number of positional roles to challenge the rigidity of a singular, monolithic authorial voice. The invitation is thus to read these texts as they unfold, like notes taken on a trip or the evolving chapters of a life in motion, one centered in serendipitous and life-changing encounters rather than a sequence rigidly organized around the definitive logic of the Logos.

The second volume of Smith’s anthology begins with a more somber tone, as Enwezor confronts the shifts in the art world—and the world at large—after September 11. “The State of Things,” written in 2015 on the occasion of the Venice Biennale that he directed, is a devastating condemnation of an art system that appears utterly co-opted by the forces of late capitalism, against the background of new forms of political and religious fundamentalism and unrelenting violence against migrants and minorities. Enwezor writes, from a place that could arguably be described as the very belly of the beast: “The current art system’s casual and unquestioning relationship to power, its love of its trappings and privileges, its very acquiescence to power, perhaps represents not only the utter farcical notion of art’s claim to radical autonomy but also its complete powerlessness to be transformative.” Considering the events of the last decade and today’s conditions, his words are nothing but diagnostic and prophetic.

Enwezor’s response to this state of things, of which he was both a protagonist and a firsthand witness, is to renew his long-term commitment to the reparatory quality of reimagined and revised historical narratives. It is in this sense that reparation, as a form of healing, can be located at the very center of his activities as a critic, historian, and curator. His last major curatorial project, perhaps the first truly global exhibition of the twenty-first century, Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965, opened at Haus der Kunst in Munich in 2016, three years before his untimely death. It was meant to be the first chapter of a three-part endeavor that would include exhibitions on the “Postcolonial,” presenting art from 1965 to 1985, and on the “Postcommunist,” covering the period after 1985.

Inevitably, there are shortcomings here, as there would be in any attempt to put forth the work of such a prolific writer. The chronological organization masks fundamental differences between the texts. Perhaps it would have been preferable to consider more closely their function and context and thus to structure them according to type (curatorial statement, review, etc.) in order to preserve their internal coherence. The selection of interviews is unfortunately narrow, as well as the choice of artists’ essays. The latter does not include examples of the noteworthy texts that Enwezor wrote on artists with whom he maintained a prolonged close dialogue: for example, Alfredo Jaar, William Kentridge, El Anatsui, and Cildo Meireles. However, Smith’s common-sense approach as an anthologist is, for the most part, welcome and effective. As is his introduction, which provides useful biographical background for a man born amongst the tragic struggles of postcolonial Nigeria, who would come to define, exemplify, and embody curatorial practice in the late twentieth century as an “exercise of pure intellectual freedom.”

Carlos Basualdo is the director of the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, Texas.