Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller

Straight to the pros: a basketball book looks at the NBA before “one and done.”

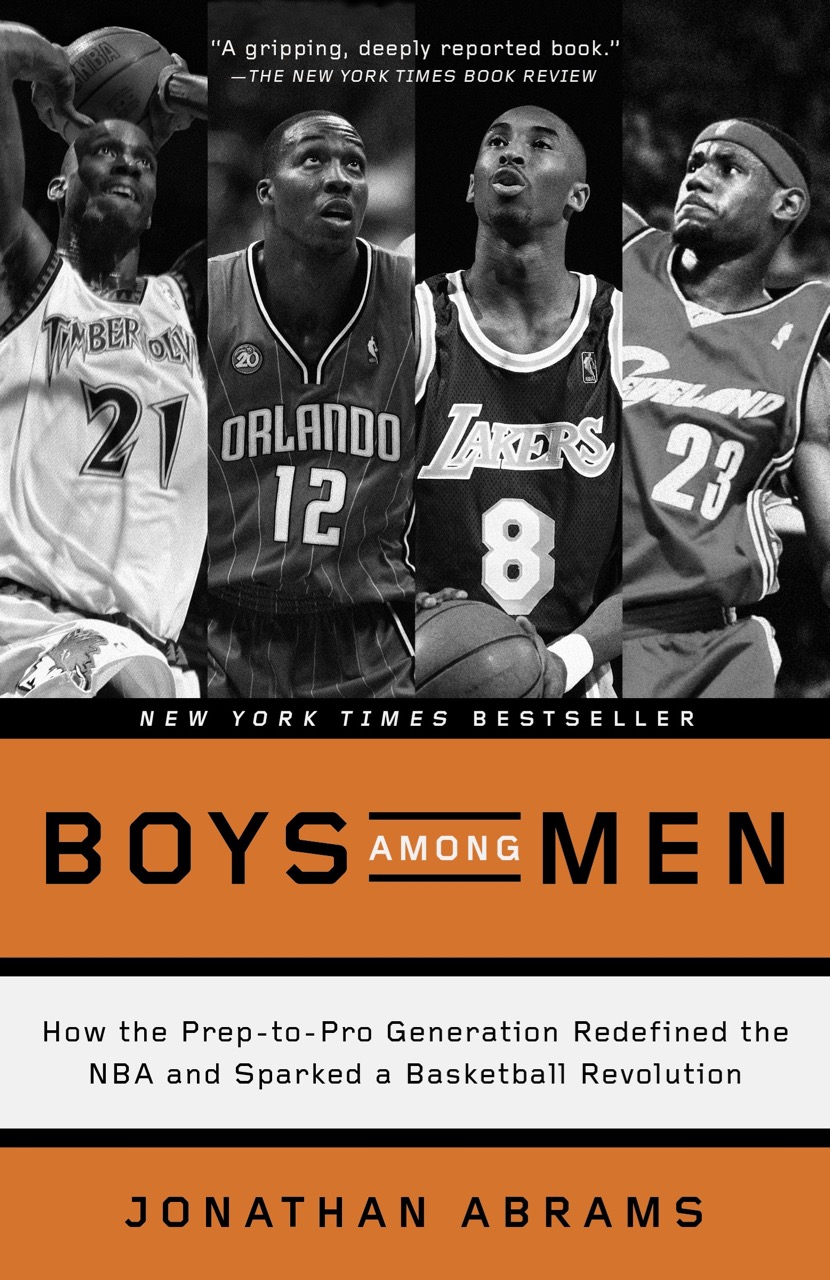

Boys Among Men: How the Prep-to-Pro Generation Redefined the NBA and Sparked a Basketball Revolution, by Jonathan Abrams, Three Rivers Press, 352 pages, $16

• • •

1.

Jonathan Abrams’s Boys Among Men—about the recently bygone era of high school students going straight to the NBA—is being released in paperback just in time for March Madness. Even while I was engrossed in the book itself, I kept blanking on the name, wanting to call it “Boys to Men,” while knowing this was incorrect. At first, I thought this was because the crooning pop group Boyz II Men had made a stronger impression on me than I ever knew. Only after I finished the book did I start to understand why I may have had this difficulty.

Abrams opens with a scene from the neolithic era of the NBA (and its now defunct rival, the ABA): it’s 1974, and a representative of the ABA’s Utah Stars “carefully placed a pile of 100 dollar bills on the orange crate that doubled as the dining room table in Mary Malone’s living room.” The Malone household has holes in the walls where the rain comes in. It’s located in the small town of Petersburg, Virginia, which was once “a civil war conflict zone.” This is the residence of Moses Malone, high school phenom, who the team is trying to entice even though he had already committed to playing at the University of Maryland. There was twenty-five grand on the table, cash. Plus, they promised to fix up the house.

Malone stuck with his Maryland commitment. But five days into his college life, Malone—unwilling to rouse himself at the required early hour—declared, “Big Mo going pro,” and signed for $3 million.

Malone was a success, but two high school players who went pro the following year, Bill Willoughby and Darryl Dawkins, had more ambiguous careers, and the phenomenon of high school players turning pro went dormant for near twenty years. And while it did, the NBA transformed. Michael Jordan joined the league in 1984, the same year that David Stern became its commissioner. The size of the TV contracts grew. So did the players’ salaries. During the transformation of the league’s fortunes, the status quo in which high school players would go to college before turning pro remained. There was a stirring with the emergence of Shawn Kemp in 1989. And then, in 1995, Kevin Garnett declared for the NBA draft straight out of high school.

2.

The four players featured on the book’s cover—Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant, Dwight Howard, and LeBron James—represent the most famous of the generation of high school kids who declared for the NBA draft in the years between 1995 and 2004. Garnett was the first of this group. James and Howard were the last. In 2005 the NBA introduced a clause that moved the minimum age from eighteen to nineteen. Thus began the strange “one-and-done” era of college basketball in which we now live.

I read Boys Among Men in a state of deep immersion that reminded me of the trancelike reading experiences I used to have as a kid when I fell into a book about sports or the Beatles—the vicarious pleasure of witnessing emergence and transcendence. Abrams introduces each player early in his life, letting us see the diamond amid a great deal of rough. Then we watch him rise within the ever more elaborate ecosystem of parents, school, coaches, scouts, general managers. We see the emergence of the sneakers companies, who are like one giant teat toward which a thousand sucklings are struggling. We witness the innovations of Sonny Vaccaro, who leveraged the lure of Adidas’s and Nike’s endorsement money to attract the best talent in the country to his ABCD summer camp, a giant open-air audition of high school players for NBA scouts.

Packed with quotes and inside information, Abrams’s narrative is a series of brief sketches of many familiar careers—Tracy McGrady, Rashard Lewis, Eddy Curry, Amar’e Stoudemire, Jermaine O’Neal, Tyson Chandler, Kwame Brown, among others. Yet even if many of these players were by most measures a success, staying in the league for years and earning enormous sums, many of them lived under the contemptuous shadow of having failed to live up to the expectation that they become superstars.

And then there are players like Lenny Cooke, who did not make it. Cooke may be the most high-profile cautionary tale in Abrams’s account. Cooke’s demise had to do with many things, among them an injury. The physical frailty of very young men who are competing with grown men for the salaries those men use to support their families is part of the story, but mental frailty is an even bigger part.

Confidence—that essential, ephemeral thing—wafts through these tales like a genie bestowing riches on some and leaving others stranded by the side of the road. Cooke owned the ABCD camp the first summer he attended. When he returned the next summer, he was being talked of as a potential number-one draft pick out of high school. But he was outdueled in the championship by another phenom, LeBron James, who hit the game-winning shot at the buzzer. Abrams implies that had James missed that shot, and Cooke’s team won, maybe it all would have been different. “Probably the most important shot a high school kid has ever made,” Vaccaro said. LeBron James now earns $30 million a year from his team alone. Cooke, meanwhile, is essentially living in a shack somewhere in Virginia. I’m tempted to say not far from where Moses Malone grew up, but I don’t know for sure.

3.

I love to play basketball, and I love to watch basketball. I would probably watch a couple of five-year-olds play one-on-one in the driveway if I had nothing better to do. That said, though I watch college games now and then, I’ve always found the television announcers—especially Brent Musburger and Billy Packer, back when they were calling games—a bit gross.

Even now, in the “one-and-done” era, they speak about the coaches, the colleges, the “program,” with such reverence, as though the players on the court should feel honored to be part of such a wonderful tradition. There is no acknowledgment that the athletic departments of these schools are autonomous free-trade zones, that the players make no money at all while everyone else involved makes millions, and that when they outlive their usefulness they are generally discarded.

Abrams quotes Kevin Garnett’s agent on the high-school-age kid’s deliberation on whether to declare for the NBA draft or go to college. “Seemed to understand the economics . . . He understood that if he went to college, they were going to sell his jersey. They were going to sell tickets. They were going to get tremendous benefits and he wasn’t.”

Even David Stern, the commissioner who instituted the age-minimum rule, is ambivalent, pointing out that young tennis players, baseball players, and golfers are not burdened by this requirement.

College is the elided event in Abrams’s book. Its presence is represented by piles of recruiting letters and beseeching visits from emissaries who plead to be heard. They are all in on a fantasy of what this kid might become. In the parlance of the game, their “upside.”

And yet college is lurking within the pages of the book, not simply as the road not taken, but as a symbol. Not a badge of status but rather of the idea of growth and evolution, of an environment that allows for development as opposed to demanding results. In other words, a place to get an education. Which is why, I think, I kept remembering the title as “Boys to Men.” I wasn’t willing to accept the harshness of the word “among.”

Thomas Beller is the author of four books, most recently J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, which won the 2015 New York City Book Award for biography/memoir. His fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, The St. Ann’s Review, Ploughshares, and The New Yorker. A founder and editor of Open City Magazine and Books from 1990 to 2010 and the website Mrbellersneighborhood.com, he is currently an associate professor at Tulane University.