Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller

Dog soldiers and literary collisions: a biography of novelist Robert Stone.

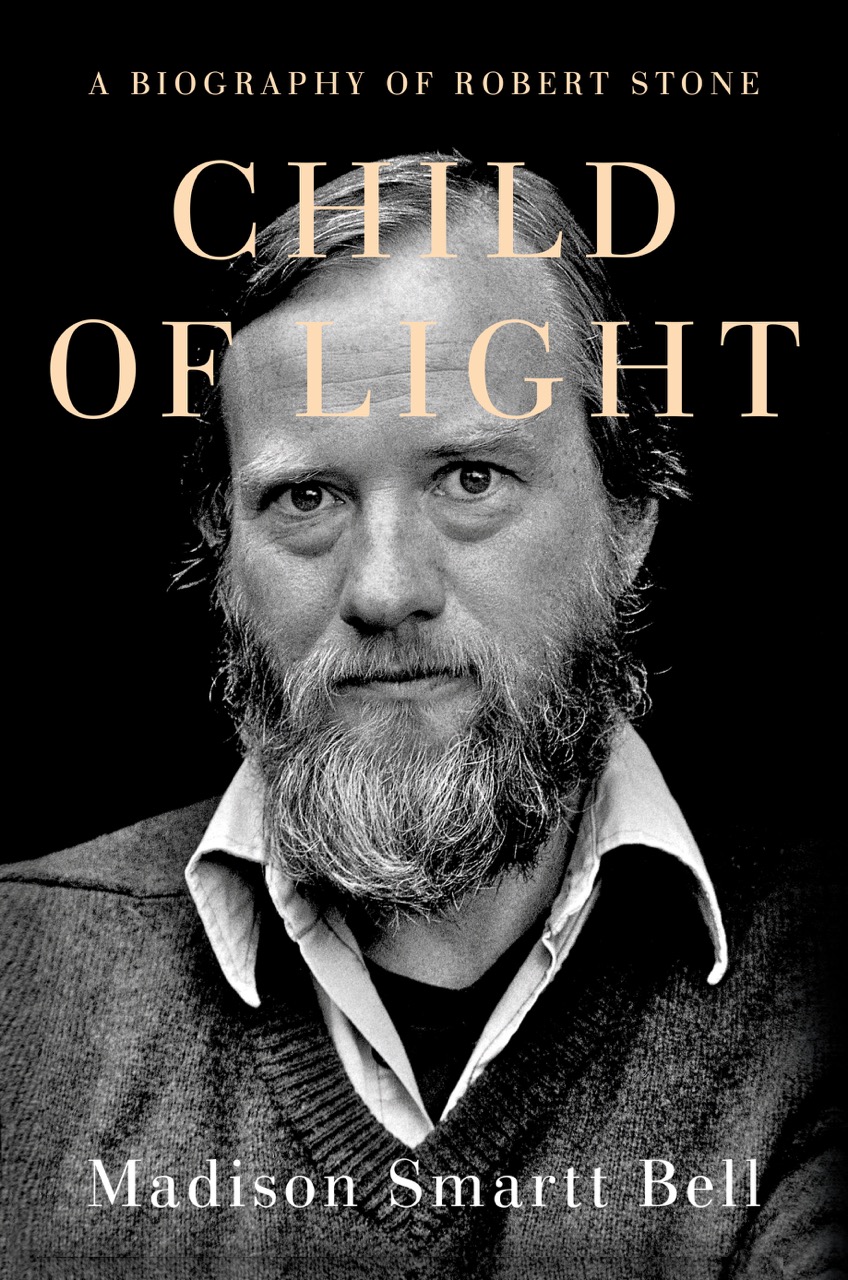

Child of Light: A Biography of Robert Stone, by Madison Smartt Bell, Doubleday, 588 pages, $35

• • •

About two-thirds of the way through Child of Light, an essential and much anticipated (by me) biography of Robert Stone, its author, the novelist Madison Smartt Bell, appears as a character in the narrative. He was friends with his subject, it turns out, or friendly enough to have arranged for them to travel together to Haiti, where Bell was researching one of his novels, in 1999.

“I was one of those readers who waited impatiently for Robert Stone novels to appear” is how Bell introduces this fact. “I burned some midnight oil in Baltimore when Damascus Gate was published in 1998,” before going on to describe their burgeoning friendship and plans to travel together.

The news that he knew his subject comes as something of a shock, even though, I later saw, he mentions it in the preface. By page 391, I had forgotten: Bell’s tone throughout is so scrupulous and matter-of-fact, the pitch of emotion rarely rising much above a police report as he unfurls the great writer’s life—the childhood, the education, the navy years, the early publications, and so on—that I had given up on something more urgent, incredulous, and self-dramatizing. In some ways, the even-keeled tone is as much an homage as the facts he has accumulated—Stone’s method was similarly clear-eyed, unflinching, and measured.

The opening of Bell’s first chapter is indicative of his method of quoting Stone and adding comment:

“I was born in Brooklyn on President Street, the border of Park Slope and South Brooklyn,” Robert Stone recalled in midlife, for a book of essays on Catholicism. The day of his birth was August 21, 1937. “My mother was a schoolteacher in the New York public school system. My father worked for the old New Haven Railroad. . . . When I was still small, my parents separated.”

Stone’s passage goes on to say that he lived on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and in Yorkville with his mother, who “was schizophrenic.” She was committed when he was five years old, after which he went to St. Ann’s at Lexington and Seventy-Seventh Street, described as “somewhere between a boarding school and an orphanage.” He was nine when he rejoined his mother.

“This account exaggerates the stability of Stone’s early years somewhat,” Bell writes, and now, revisiting just this one passage, I start to understand the self-reserving rationale for Bell’s measured tone, and maybe even for Stone’s cool rendering of characters in states of extreme duress—there is a lot in Stone’s life to feel amazed at. True of his books, too.

Bell juxtaposes the above summary with an interview Stone gave to Ann Greif, a scholar with a psychoanalytic approach, in the late 1970s: “My mother didn’t have an honest bone in her body, God bless her,” Stone said. “She was a real outsider. . . . She really didn’t give a shit about anybody except me and her. But she did care about me.”

The Greif interview is one of many sources Bell weaves together. The most important is Stone’s wife, Janice. They married young and stayed together for the duration. In some ways, Child of Light is as much a biography of a marriage as it is of a writer, and toward the end Stone’s books come to seem almost like collaborations with Janice, just as Bell’s biography is buttressed by her work as an archivist, interlocutor, and writer. (She is working on a memoir of her own, as is her daughter, Deidre.)

Child of Light proceeds chronologically and is organized around the novels. For the Stone aficionado such as myself, it is strewn with gifts. I had always marveled at the strange voice that was the underpinning of his writing and which was manifest in the speech of the man himself—a curious mix of a plummy upper-class accent out of Katharine Hepburn movies, and an old-school New York accent of the sort that was probably last heard coming from the front of a Checker cab. The explanation can be found in his classy, crazy mother, and perhaps also in that school that was “somewhere between a boarding school and an orphanage.” I was always amazed at the opaque role of autobiography in his novels—wondering at the overlaps between Stone and the most Stone-like characters—and Child of Light helps clarify his technique of splitting parts of himself up and doling them out to the many central characters in his collision-course plots. You could call it the schizophrenic style, or you could just call it fiction.

The passages in which Bell is present mostly take place in Haiti. At the Cap Haïtien airport, “a cobble of tin-roofed, mostly open-air buildings,” at the end of their second visit together, Bell asks his companion “if he knew where that pink slip was” handed to him by immigration authorities upon his arrival. Stone did not. What follows is a suspenseful set piece whose finale is a desperate scene in which Bell lobs lie after lie at an impassive customs official, trying to get Stone out of the country in the absence of the pink slip.

“He never received the pink slip in the first place. A maid in the hotel must have thrown it away. A crow flew in the window and carried the pink slip off to its nest.”

Nothing works. “The tin roof had hit a temperature to melt brass.”

It’s the truth that sets them free: “Okay. He is a negligent man. He lost it,” Bell states.

The customs official relents, sending them off with the admonition, “You may go, but you must not tell lies.”

On first reading, I enjoyed this scene for its drama, color, and comedy, not to mention the sense of relief upon learning that one’s literary heroes can be as disorganized and self-defeating in their travels as oneself. (It was a huge gift to discover, elsewhere in the book, that Stone, a man of adventure and daring in life and writing, tended to have panic attacks before he set off on his most outlandish expeditions, and almost bailed on the trip to Vietnam that became the basis for his most celebrated and probably best novel, 1974’s Dog Soldiers.) Looking at the airport episode again, I can better appreciate the subtle ironies of this admonition being made to a pair of novelists/authors.

In 1986, speaking at a literary conference in Sicily sponsored by PEN American Center, Stone remarked: “Life in collision with language produces the necessity of interpretation. We cannot take things whole all at once; we would be swept away.”

Collisions play an important role in the novels of Robert Stone. He tended to develop plots in which several discrete characters move through time like figures lost in a maze. A reader can see each one of them, but much of the narrative tension involves anticipating, and slowly perceiving, the ways these different characters will crash into one another. Once, at a reading, I heard an audience member posit that Stone’s first three novels, A Hall of Mirrors (1967), Dog Soldiers, and A Flag for Sunrise (1981), were as strong an opening trio of novels as any written by an American. I would agree with that assessment.

The second half of the quote, about not being able to “take things whole all at once,” feels ironic in a biography as sweeping and meticulous as this. Bell gives us all the many pieces of Stone’s life and the composition of his writings, and some analysis, as well. It’s an illuminating appendix to a master’s body of work.

Thomas Beller is the author of four books, most recently J. D. Salinger: The Escape Artist, which won the 2015 New York City Book Award for biography/memoir. His fiction has appeared in the St. Ann’s Review, Ploughshares, the New Yorker, and Best American Short Stories 1992, edited by Robert Stone. A founder and editor of Open City Magazine and Books from 1990 to 2010 and the website Mrbellersneighborhood.com, he is currently an associate professor at Tulane University.