Andy Beta

Andy Beta

Cloudward and onward: the musician finds a newfound steadiness in her latest album.

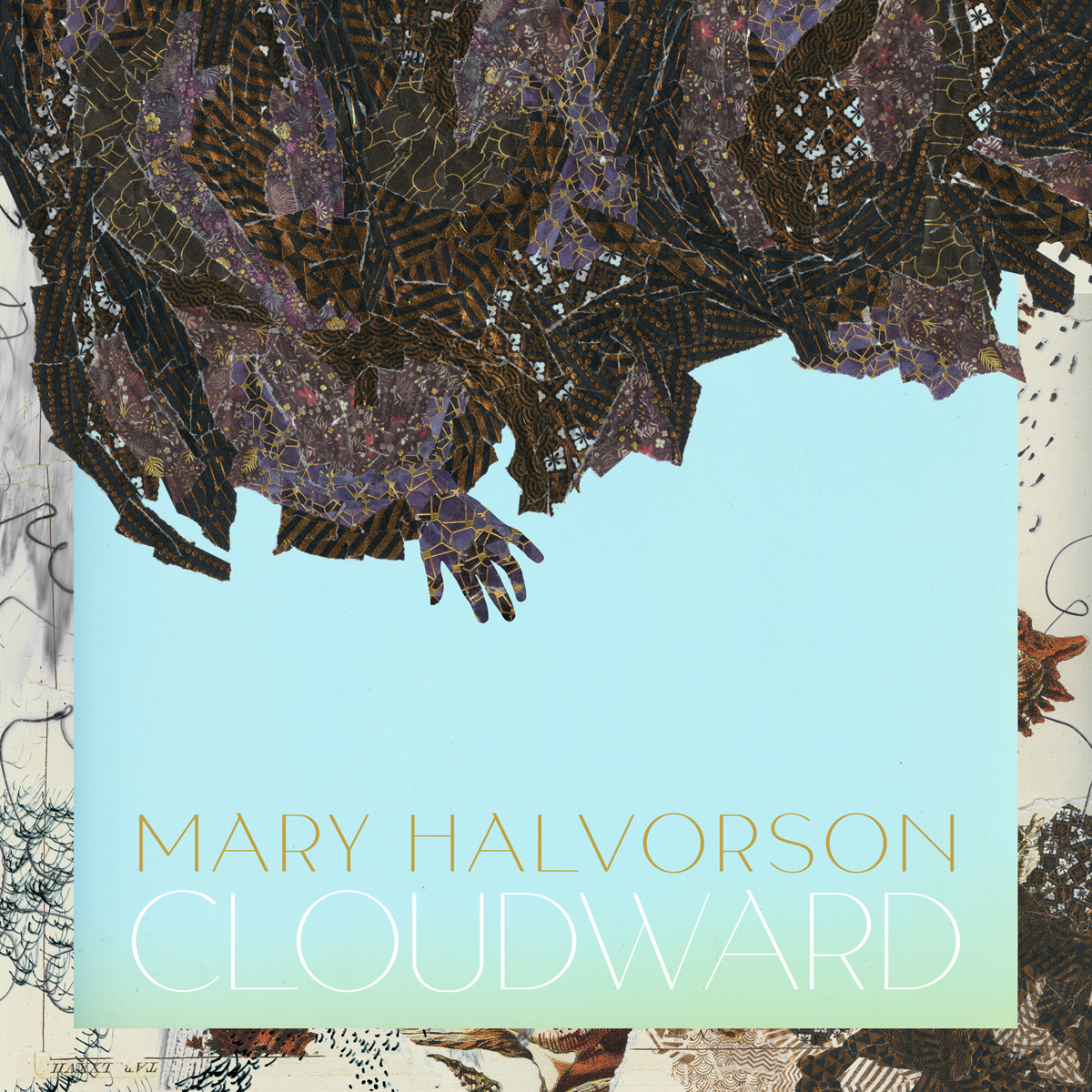

Cloudward, by Mary Halvorson, Nonesuch Records

• • •

Mary Halvorson’s Class of 2019 MacArthur Fellowship bio lists her as a guitarist and composer, but her real instrument is rupture. A generational talent on guitar, the forty-three-year-old has worked with jazz legends like Anthony Braxton; Tom Waits’s guitarist, Marc Ribot; Deerhoof’s John Dieterich; Xiu Xiu drummer Ches Smith; and fellow MacArthur grantee, cellist Tomeka Reid. If you hear her in a group setting, Halvorson’s sound is recognizable in an instant: combustive, guttural, surrealistic in its instant warpage of everything around it. With her reliable Line 6 DL4 pedal, she can be in-flight turbulence, a rend in the space-time fabric, a quiet evening at home interrupted by a cat hair ball.

Rupture is there in her 2015 solo debut, Meltframe, in which Halvorson ripped open standards and splintered the demarcations between jazz, indie, and noise, pushing beyond boundaries into something disruptive and thrilling. In her other long-running groups, like Thumbscrew and Mary Halvorson Quintet, she continually finds new wrinkles, like slotting pedal-steel player Susan Alcorn into her octet (on 2016’s Away With You). But what to do when the world itself offered up the largest rupture of all—the COVID-19 pandemic that brought society to a grinding halt?

It became a blessing for Halvorson. “Part of what was so great about the pandemic was having all this time and not being like, ‘Oh, I only have two hours to work on this today,’ ” she told writer Peter Margasak about those few disjointed years. So while some might have gone insane from sheltering in place, Halvorson was finally off the hamster wheel that is reality for a professional musician perpetually racing around for gigs, tours, and recording dates. Suddenly she had all the freedom in the world to write. This yielded two books of interconnected music: 2022’s dense, gemlike double release on the Nonesuch label, Amaryllis and Belladonna. Amaryllis was scored for her sextet, with the Mivos Quartet joining for half the pieces, while Belladonna found her amplified guitar in conversation with the quartet’s classical strings. Taken together, Amaryllis and Belladonna was her grandest statement to date, engendered by “one of the more bizarre time periods I’ve experienced in my life,” as Halvorson writes in the press release for her latest, Cloudward.

Mary Halvorson. Photo: Michael Wilson.

Her Nonesuch follow-up, released this month, spends more time in the worlds imagined on Amaryllis. When the pandemic turned from disruption to new normal, routine lurched back “like a creaky machine starting up again,” she says. Cloudward was conceived after she had gladly returned to her hectic schedule of performances and hauling out to JFK with a “renewed sense of gratitude,” if one can maintain such a feeling amid the purgatorial drudgery that is commercial air travel. The band is tight and focused on bustling opener “The Gate,” following a zagging, wobbling melody that suggests Thelonious Monk racing through a crowded terminal to catch a flight.

Cloudward’s eight compositions reveal an artist moving beyond rupture toward something steadier and more stable. To start, the Amaryllis sextet remains wholly intact, a rare instance of Halvorson not adding or swapping out instruments and players between albums. The frontline of trumpeter Adam O’Farrill and trombonist Jacob Garchik brightens and furthers the themes, bassist Nick Dunston and her longtime drummer Tomas Fujiwara keep everything streamlined, and Patricia Brennan’s vibraphone work provides an X factor much like Halvorson’s own guitar once did.

Mary Halvorson. Photo: Michael Wilson.

Trusting her ensemble, Halvorson often recedes into the background, so that when she does step to the fore for an ear-warping solo, it feels all the more effective. Take the opening minute of “The Tower,” where her strings fidget, scratch, then scramble like a fast-forwarded tape, making everything decidedly off-kilter before the introduction of Brennan’s vibraphone leads us to the sublime lift of the piece. Brennan’s presence most readily harkens back to fellow vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson and his work on Blue Note sessions throughout the ’60s, when hard bop gave way to avant-garde experimentation (before everything melted into fusion). By turns grounding and weightless, the metallic shimmer of the vibraphone imparted an ethereal atmosphere to the tight matrices of sessions like Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch, Andrew Hill’s Andrew!!!, and Grachan Moncur’s Evolution. Brennan’s vibes similarly put you up in the clouds, making for one of the dreamiest compositions in Halvorson’s catalog to date, as gorgeous as the hovering strings of Belladonna’s “Moonburn.” Such serenity carries over to “Collapsing Mouth” and “Unscrolling,” O’Farrill’s solo on the former a standout of the album, while the latter accentuates Fujiwara’s near-subliminal rhythmic presence.

If I hadn’t looked at the credits, I might not have realized that “Incarnadine” features a string exchange between Halvorson and lone album guest (and fellow labelmate) Laurie Anderson on violin. Both players are attuned to each other’s movements, and what might have combusted into fretwork fireworks just a few years ago is now finespun, deftly interwoven into the group dynamic. Only at the midpoint of the record—on “Desiderata”—does one of Halvorson’s distorted solos finally break through to provide that disrupting visceral thrill of yore, feeling dramatic—and cathartic—when it hits. It’s the type of midair turbulence that makes the smooth ascent of Cloudward startling in hindsight.

In a recent New York Times appreciation of Monk, Halvorson’s observations of the legendarily idiosyncratic pianist-composer seem to reflect her own newfound sensibilities: “You can feel Monk isn’t trying to do anything tricky; he’s just being himself. Underneath the wonderfully twisted logic, it’s still a melody you can sing along to.” Halvorson’s older works accentuated the skewering of clarity and noise, but you can almost hum along with everything here, including the crystalline vibraphone line that runs through closer “Ultramarine.” Previously, Halvorson’s guitar might have burst in to jolt the proceedings, but now she cagily nudges it toward a giddy high. Rather than relying on rupture, Cloudward finds Halvorson adding something new to her tool kit: a refinement born of consistency, group cohesion, and restraint, and the music is all the more breathtaking for it.

Andy Beta has been writing about music for twenty years. He is working on a book about Alice Coltrane.