Hannah Black

Hannah Black

Christina Sharpe pulls apart language to describe the indescribable aftermath of slavery.

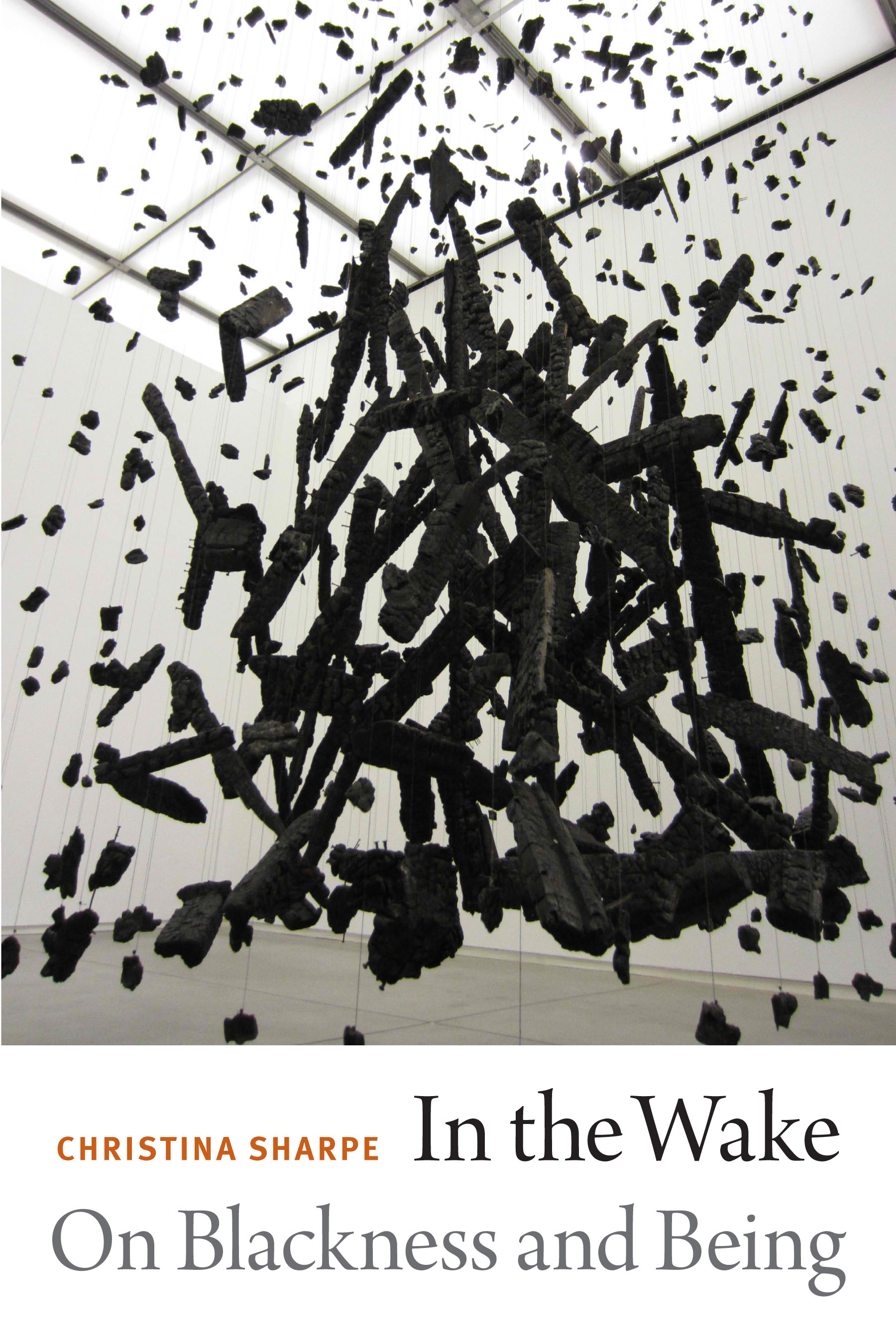

In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, by Christina Sharpe, Duke University Press, 175 pages, $22.95

• • •

Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being proceeds from an image of the long afterlife of transatlantic slavery as a wake trailing behind a ship, playing on the word’s other meaning as a watch kept over the dead and echoing the widespread use of “woke” to mean politically aware. “I am interested in ways of seeing and imagining responses to the terror visited on Black life,” writes Sharpe, “and the ways we inhabit it, are inhabited by it, and refuse it. I am interested in the ways we live in and despite that terror.”

Each of the book’s four chapters takes a single term from the history of transatlantic slavery—“The Wake,” “The Ship,” “The Hold,” “The Weather”—and makes a case for its persistence into the present day. Anti-blackness exists not because of some amorphous fear of the unknown or mysterious viral tendency toward racism, but because of this specific history of Black diaspora and white capitalist violence, and the continuing interrelationship between the two. Five hundred years of slavery scattered people of African descent all over the world, a dispersal enacted on us not as workers, adventurers, or bureaucrats, but as things. The story of how these stolen people became commodities then became Black people and survived as such is breathtaking and strange; how can this inexpressible loss be expressed in language?

On this impossible ground (not really a ground, but an ocean becoming ground), Sharpe stakes out a space between the immediacy of suffering and the mediations of language. She draws on Maurice Blanchot’s theory of disaster as an event that “wrecks language,” and accordingly the book offers a vocabulary of repurposed everyday terms in order to discuss anti-blackness. Everyday life and language maintain and reveal the patterns of violence generated by slavery. In the chapter “The Hold,” Sharpe traces this word from the belly of a ship via the cops and wardens who enforce the contemporary manifestation of the hold (in a striking observation, Sharpe describes the cellphone picture Oscar Grant took of the transit cop who later killed him as having been “shot from the angle of the hold”), to the necessity of, despite everything, holding each other: “Across time and space the languages and apparatus of the hold and its violences multiply; so, too, the languages of beholding. In what ways might we enact a beholden-ness to each other, laterally?”

The prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes racism as the “production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” This vulnerability is not only a matter of police executions: Black people as a group tend to have less access to life-sustaining resources such as healthcare, good schools, and safe housing, and are more likely to suffer from stress-related illnesses and severe mental disorders. Although many contrive to forget how Black people came to be here, and to blame this catastrophic situation on Black people themselves, we all must, as Sharpe’s work affirms, contextualize Black suffering in a long history of structural anti-blackness. The ability to forget history is a privilege, and a violence.

The story of Sharpe’s family, plagued by illness and violence despite a semblance of class mobility, bears this out. The book begins with “The Wake,” a very personal chapter on the many bereavements suffered by Sharpe, illustrated with family photographs: “This would be the second time in my life when three immediate family members died in close succession . . . we survived the deaths of my nephew Jason Phillip Sharpe; my mother, Ida Wright Sharpe; and my eldest brother, Van Buren Sharpe III. As this deathly repetition appears here, it is one instantiation of the wake.” This memoir element never returns, though the terms of this disappearance are clear: the rest of the book exists in the wake of its first chapter, just as its writer lives in the wake of the events its first chapter describes.

Moving out from there through a series of examples, in Haiti, in the USA, in France, and elsewhere, Sharpe finds Black people still extraordinarily vulnerable to harm, still disturbed by the wake of the ship. She mobilizes various examples, mostly from news stories, often involving little girls: “Mikia Hutchings . . . a Black twelve-year-old girl child, caught with her white girlfriend writing on a school wall, faced with a possible felony because her family was unable to pay the hundred-dollar restitution fine”; “a Haitian girl child, ten years old at the most . . . lying on a black stretcher”; “Dasani Coates, an eleven- and then twelve-year-old Black girl child, and her family (seven siblings and two parents), who live in one of New York City’s family shelters.” Sharpe is fully aware of the ways that the media spectacularizes Black pain for white consumption, especially through the white image of the ultra-violent Black cis man, and so her work foregrounds the everyday vulnerability of Black girl children refused childhood and girlhood from the time of slavery up to the present: “never really a girl; at least not ‘girl’ in any way that operates as a meaningful signifier in Euro-Western cultures; no such persons recognizable as ‘girl’ being inspected, sold, and purchased at auction in the ‘New World’.”

Being in the wake, Sharpe tells us, is an ethical choice as much as a condition. It’s keeping watch as much as losing ground. Among many other terms, Sharpe proposes her procedures of “wake work” as a form of “underwriting.” Evoking the shipping insurers who underwrote slave traders’ financial losses (as if they were only that), Sharpe’s underwriting pays conscious attention to the Black loss that subtends capitalism, even as it also reflects the impossibility of fully grasping this loss. In performing this underwriting, she often opts for collage over exegesis, stitching together many different examples and quotes to form an image of slavery’s persistence. The theorist Hortense Spillers’s phrase “hieroglyphics of the flesh” is supplied with an opaque definition by another theorist, Saidiya Hartman—“the gap or incommensurability between the proper name and the form of existence that it signifies”—and Sharpe glosses neither, instead “ushering here, into the gap, Black annotation together with Black redaction” . . . and it goes on like that, with no particular term ever coming into focus. All the terms expand out, wake-like, to advertise the fact of a metonymic ship. Understood literally as something less than writing, “underwriting” could be a kind of rigorous anti-rigor, determined to keep connections loose, to stay in free association.

If Sharpe’s layering of phrase upon phrase at times resembles the wordplay of post-structuralist thought, it is important to remember a couple of things. First, white critical theory has for the most part failed to even try to make itself adequate to slavery, though slavery is one of its conditions of possibility: even Blanchot had nothing to say on the subject, though he once wrote that “we surrender to sleep, but in the way that the master entrusts himself to a slave,” suggesting at best a subconscious awareness of what Sharpe terms “the everyday of Black immanent and imminent death.” In the light of theory’s disavowal of slavery, In the Wake charges itself with blackening theory as much as theorizing blackness. Second, recall that Black resistance has often taken the form of great, weird feats of language, evidenced everywhere from the still-spoken creoles invented by enslaved Africans in order to speak to each other, to the enormous global popularity of rap. Faced with the inconceivable fact of her own origin in an incomprehensible terror recorded primarily in “hieroglyphics of the flesh,” what is the conscientious writer to do but attempt to speak in tongues?

“Underwriting” also echoes Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s concept of the undercommons, but while the undercommons is a militant collectivity that is typified by but not limited to Black life, the underwriter feels closer to the undertaker, in that her concern is primarily Black death. Mourning can be and has been a politics, but it must avoid becoming only a litany of horrors. Refusing melancholy in favor of care, In the Wake understands mourning as a practice embedded in living, and vice versa. Sharpe’s beautiful book enacts this indistinctness through pulling language apart and putting it to new purposes.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer from the UK. She lives in Berlin. She has previously written for Artforum, The New Inquiry, Afterall, Texte zur Kunst, and a number of other publications. Her book Dark Pool Party was published by Dominica/Arcadia Missa in February 2016.