Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

Toil and trouble: a group exhibition explores the complications of labor.

A new job to unwork at, installation view. Photo: Mark Waldhauser. Image courtesy Participant Inc.

A new job to unwork at, Participant Inc, 253 East Houston Street, New York City, through October 14, 2018

• • •

Though perhaps best known for its unique scorched-earth version of feminism, Valerie Solanas’s 1967 incendiary and inspiring SCUM Manifesto is equally a theoretical tract about labor, calling for the total destruction of “the money-work system.” For Solanas—no less than for many feminist Marxist thinkers—the oppression of women is bound up with the economic conditions of capitalism, and the only path for escape out of patriarchy is a radical reenvisioning, indeed a refusal, of the category of work. “SCUM will become members of the unwork force, the fuck-up force,” Solanas writes. “SCUM office and factory workers, in addition to fucking up their work, will secretly destroy equipment. SCUM will unwork at a job until fired, then get a new job to unwork at.”

A new job to unwork at, installation view. Photo: Mark Waldhauser. Image courtesy Participant Inc.

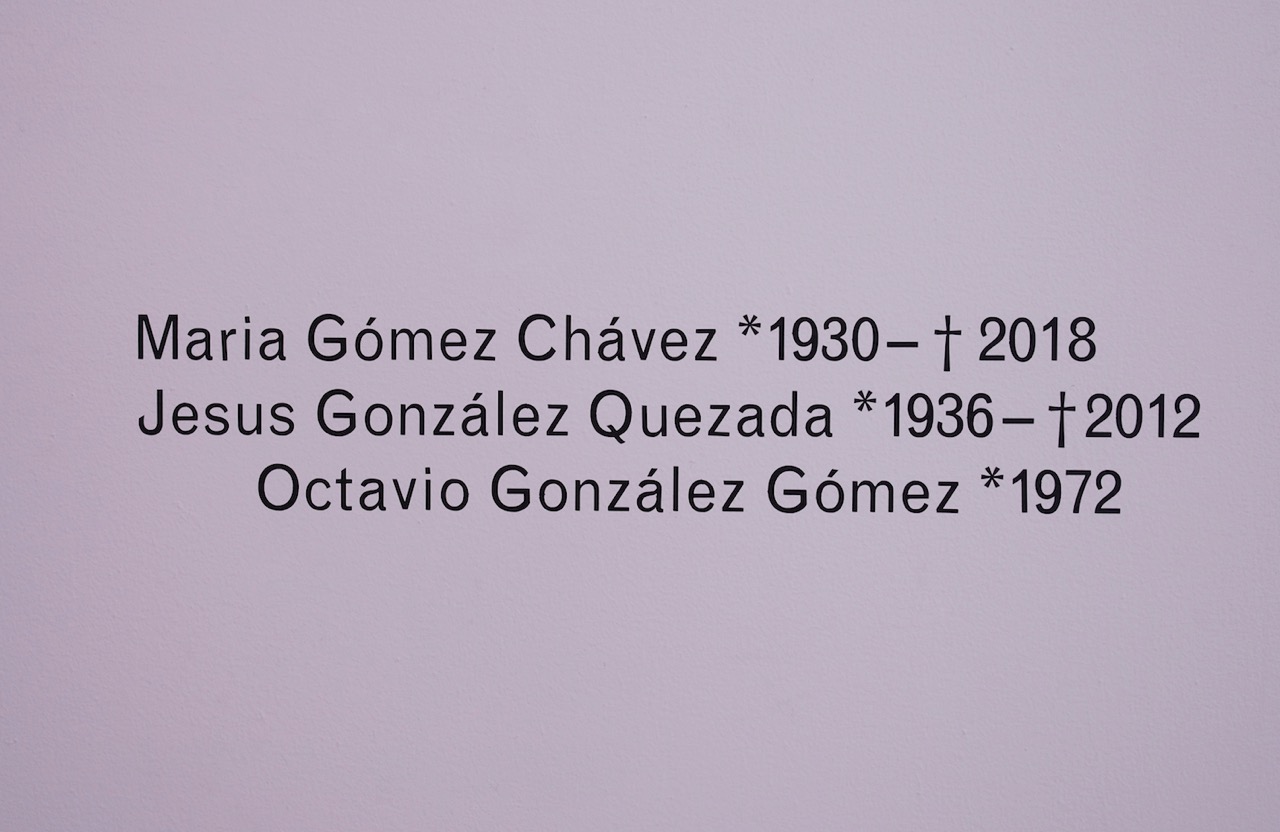

Taking its title directly from Solanas, the exhibition A new job to unwork at (curated by Andrew Kachel and Clara López Menéndez) brings together eight artists and one collective who grapple with what gender studies scholar Kathi Weeks has termed “postwork imaginaries.” The result is laudably ambitious if somewhat aesthetically uneven. A few pieces fall a little flat, such as an oversized voided check by Dylan Mira (2015), but most are poetic and open-ended, including Mira’s 7 Skin Night Repair Essence (2017), an ersatz fountain that is redolent of bodily toil and tactile ministrations. Other artists, such as Wes Larios and Karin Schneider, make thoughtful contributions that render legible normally occluded familial reproductive labor and networks of informal queer kinship. For his evocative Acknowledgements (2018), Larios installed an homage to his grandmother at the margins of the gallery (a spare list of names and dates inscribed in doorways and on the metal air duct near the ceiling). The first member of his family to immigrate to the US, she helped ensure financial stability for the clan through a series of marriages and hence laid the grounds for the conditions of possibility for Larios’s artmaking.

Wes Larios, Acknowledgements, 2018 (detail). Vinyl text. Photo: Mark Waldhauser. Image courtesy Participant Inc.

One of the most interesting aspects of the show is how pieces from the 1970s and early 1980s are deployed as counterpoints to the more contemporary work—suggesting how persistent, and persistently vexing, this topic is. An example is Create-A-Clock (1978), by Fred Lonidier, the San Diego artist and stalwart union activist who has, for several decades, explored issues around occupational safety. His project intervenes in a make-your-own-clock kit to juxtapose the regimentation of remunerated factory time with the ostensible leisure of unpaid family time—though as Solanas and organizing efforts like the 1970s Wages for Housework Campaign both realized, for women the domestic sphere is hardly free play.

A new job to unwork at, installation view. Photo: Mark Waldhauser. Image courtesy Participant Inc.

On view on low monitors in the middle of the gallery are two major additional historical touchstones: video documentation of Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance (Outdoor Piece) (1981–82) and Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s Sanman Speaks (1977–85). In Hsieh’s thirty-minute compression of his full calendar year living in a sleeping bag and attempting to never enter a building, subway, car, tent, or any other dwelling, we see many moments of the artist’s self-imposed deprivations, but also instances of tenderness and generosity on the part of those who help keep him fed. When Hsieh is arrested after an altercation, it is hard to read what motivates his genuine panic about being forced to go inside—is this fear related to his status as an undocumented immigrant, or fear that the integrity of his own strictly bounded endurance performance will be compromised? Hsieh’s piece raises productively unresolvable questions about the parallels and disjunctions between the precarities of statelessness, the insecurities of involuntary homelessness, and the desires and commitments that can accompany unwaged artistic practice.

Ukeles offers a model of solidarity between differently valued forms of labor in an hour-long video that presents her conversations with sanitation workers in New York City about the hostilities they face from the public and about their dilapidated facilities, such as barely functioning locker rooms. The artist shakes their hands and thanks them individually, and many of the sanitation workers also thank her—that this simple gesture of mutual respect is still unusually moving, some thirty years later, indicates that the bar is set tragically low for expectations about cross-class interactions, not to mention those that are cross-gender and cross-race.

A new job to unwork at, installation view. Photo: Mark Waldhauser. Image courtesy Participant Inc.

In addition to serving as centerpieces of A new job to unwork at, Hsieh and Ukeles were both featured in the influential exhibition Work Ethic, curated by Helen Molesworth at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2003, and both make appearances in the recently released Whitechapel/MIT Press volume Work, edited by Friederike Sigler, an anthology that sports a photograph of Ukeles on its cover (full disclosure: my writing appears in Molesworth’s exhibition catalog and in Sigler’s volume). There is a reason that these two figures have become vital to so many recent conversations about art and labor: both artists are at once emotionally affecting and complex in their treatment of the way privilege functions in relation to race, gender, class, and (invented or real) affinity. Or maybe they are so affecting precisely because they are so complicated; in divergent ways, Hsieh and Ukeles demonstrate that confronting the topic of work through the framework of art takes many long, hard hours. Years. A decade. A lifetime.

Indeed, the objects, texts, and videos on view in the narrow gallery space of Participant Inc are only one facet of Kachel and López Menéndez’s larger, ongoing project about unworking, one that crucially includes the racialized politics of care and the importance of pleasure. Along with organizing the exhibition, the curators also hosted a research residency, compiled a reader of source material (a different reader on offer was assembled by Kandis Williams of Cassandra Press), sponsored two workshops with Coop Fund (an experimental funding platform for artists), and launched a series of public programs that included a collaborative song-writing performance by Amelia Bande (Punching Songs Together), a dialogue between scholar Weeks and Lise Soskolne of W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy), and a film screening of two experimental documentaries (JoAnn Elam’s Everyday People, 1978–1990, and Kevin Jerome Everson’s Company Line, 2009) selected by independent curator Karl McCool.

Punching Songs Together, 2018. Musical performance by Amelia Bande with susan snooze karabush, Neyza Honore, Alice Ashton, and Constantina Zavitsanos.

The global relations generated by the unevenly compensated realm of work, and the inequities it produces, are vast, and—as the variably visually compelling objects in this show illustrate—can be resistant to imaging. In her conversation with Weeks, Soskolne called W.A.G.E.’s ongoing efforts toward a more just wage structure for artists “a demand and a refusal.” She stated that “the demand must contain within it a critique of the problem that is so searing that it renders the demand itself inadequate to the enormity of the problem.” Unworking is one possible route toward that critique, as is Solanas’s exhortation that, as a feminist and queer collective, we grab for ourselves “some thrilling living.”

Julia Bryan-Wilson is spending the 2018–19 year as the Robert Sterling Clark Visiting Professor at Williams College. Her book Fray: Art and Textile Politics won the 2018 Robert Motherwell Award, and a Korean translation of her influential Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (2009) is forthcoming from Youlhwadang Press.