Julia Bryan-Wilson

Julia Bryan-Wilson

An artist interrogates the convergence of bodies, memory,

and the Middle Passage.

Lubaina Himid, Between the Two my Heart is Balanced, 1991. Courtesy Tate. © Lubaina Himid.

Lubaina Himid, curated by Michael Wellen and Amrita Dhallu, Tate Modern, London, through July 3, 2022

• • •

Though she is best known for winning the 2017 Turner Prize—the oldest-ever awardee and the first Black woman to claim the honor—Lubaina Himid, now sixty-seven, has been making waves in the UK since helping launch the British Black Arts Movement in the early 1980s. Working as a curator at the Rochdale Art Gallery in Greater Manchester under the feminist leadership of Jill Morgan, Himid organized a number of signature exhibitions there and elsewhere, including Five Black Women at London’s Africa Centre in 1983. In these shows, she drew on her training as a theater designer to arrange gallery installations; in her artistic work as a painter and sculptor, she also evinces an exacting attunement to how bodies, objects, and materials occupy space.

Approaching both picture frame and museum exhibition as opportunities for dramatic composition, Himid puts special pressure on the poses of her painted subjects—whether observing, assembling, embracing, or conversing—to convey meaning. An opening wall text by Himid proclaims “audiences as performers,” and she emphasizes that where one decides to stand in relation to her work, and how one interacts (or not) with it, are not neutral choices. In other words, she choreographs viewers to move through scenes, taking on the thrilling tasks and bedeviling problems of spatialization that are common to both curator and dramaturg. Himid’s command of skills around sequencing is demonstrated at every turn in her magnificent retrospective at Tate Modern. Organized by Michael Wellen and Amrita Dhallu, the show includes canvases, found-object installations, wooden cut-outs, ceramics, and sonic environments (created in collaboration with Magda Stawarska-Beavan) that together make a convincing case for Himid’s centrality to contemporary art.

Lubaina Himid, installation view. Photo: © Tate (Sonal Bakrania). Pictured: Lubaina Himid, A Fashionable Marriage, 1984–86.

This centrality is everywhere on display in both form and content, from Himid’s engagement with themes of Black Atlantic loss, queer embodiment, and woman-of-color practices of care, to her disregard for the tired bifurcation of representational versus abstract. Though figuration has achieved a comeback in recent years, it is worth remembering that many artists committed to visual storytelling were swimming against the tide of market preferences throughout much of the later twentieth century. Himid has long navigated a striking and original third path out of this stifling false binary as she freely adopts a range of sources that she rightly claims as her own. Some paintings draw from textile traditions, including finely observed fashion details and the vivid meshes of woven cloth; others turn to interiors, furniture, and the architectonic structures of the built environment. Still others present art-historical nods to the white masculinist Western canon. A Fashionable Marriage (1984–86), her scathing riff on Hogarth that takes on the UK’s conservative political and art worlds in the 1980s, features a theatrical tableau with prop-like caricatures of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in a grotesque flirtation. Himid elevates the Black figures who were marginal to Hogarth’s depiction of aristocratic manners to the role of dignified protagonists who signal alternative histories and resistance—one, a woman with a basket of books at her feet, casts a knowing sidelong glance at these posturing leaders.

Lubaina Himid, Freedom and Change, 1984. Courtesy Tate. © Lubaina Himid.

In Himid’s tapestry Freedom and Change (1984), a couple of Black women (lovers? sisters? friends?) in textured dresses run together, holding hands in a gesture reminiscent of Picasso’s Two Women Running on the Beach (1922). Himid has decisively altered the mood by adding, in front of the central pair, a pack of black dogs that extends outside the frame and charges forward along the wall; and by setting, behind the couple, two white male heads, seen in profile, low near the floor. The women seem less to be caught in a moment of dancerly abandon than determined and powerful, aware of and outpacing the surveilling, rapacious men that trail them. That so many of her figures are portrayed on the shore is of great significance, for Himid returns again and again to the sea as both metaphor and lived reality, “in the wake” as Christina Sharpe notably formulates in her book of that title, of the watery traumas of the transatlantic Middle Passage.

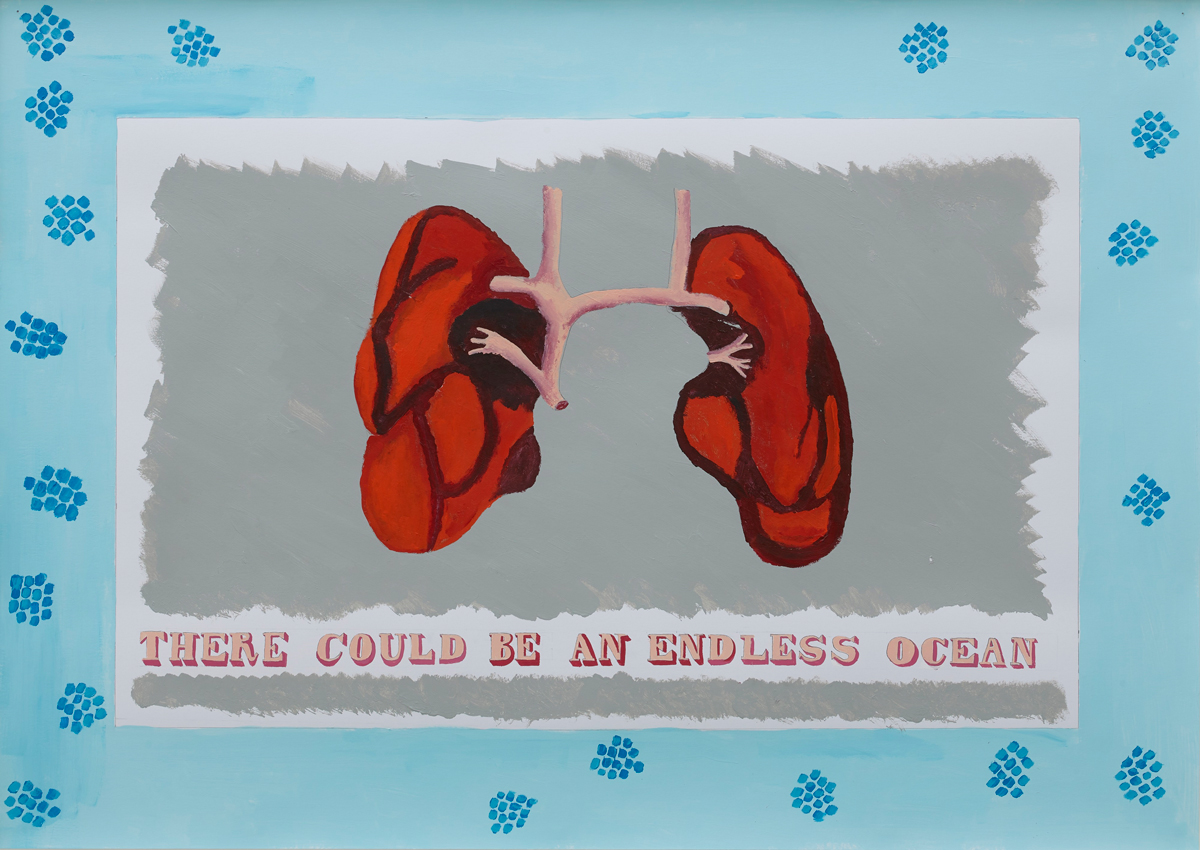

Lubaina Himid, There Could Be an Endless Ocean, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens.

In the hallway that leads audiences to the entrance of the show, banners evoking East African kanga fabrics hang from the ceiling, setting an interrogative tone with open-ended questions and evocative phrases. One places the text “THERE COULD BE AN ENDLESS OCEAN” under a pair of bright red lungs; this conjunction crystallizes the way Himid’s art proposes theories of how memories of the sea are carried within bodies as vessels of history. Waves, aquatic colors, and tides pulse and flow through the exhibition, not only as recurrent imagery but also as soundscapes, such as the lapping water and creaking wood that resonate in Old Boat/New Money (2019). The work’s sculptural component consists of an undulating crest of wooden planks; on their ends are painted designs of cowrie shells, an echo of African diasporic material cultures of trade and ornamentation. Himid’s relay between textile pattern and ocean currents is not fanciful, but rather conjures how the economics of cloth production have depended on the labors of enslaved people forced to cross the sea.

Lubaina Himid, installation view. Photo: © Tate (Sonal Bakrania). Pictured, center left: Lubaina Himid, Old Boat/New Money, 2019.

In the show-stopping installation Blue Grid Test (2020), Himid has encircled a room with an eye-level row of ordinary things—newspaper, banjo, cardboard box, headboard, wall clock, paper shopping bag—on top of which she has painted a continuous strip. Like an oceanic horizon line, the band is comprised of patterns in various shades of blue. Each of the sixty-four patterns has been sourced from decorative lineages spanning the globe, and each is a possible portal to a different past. The audio by Stawarska-Beavan takes off from Joni Mitchell’s song “Blue”—the singer calls it her “foggy lullaby”—as it weaves together observations about the color blue spoken in three languages (English, Flemish, French). Bathed in sound and overwhelmed by the social and aesthetic nuances of Himid’s careful succession of objects—some imbued with Afro-Atlantic associations, like the banjo—and her painted adornments, I wanted to spend all day in there.

Lubaina Himid, Blue Grid Test, 2020. © Lubaina Himid.

Just as the abstract-ish elements of this show are compelling, so too are the more narrative works. If in reproduction Himid’s figurative paintings can sometimes appear flat or too consciously arranged, in person they reveal that her staginess is a necessary critical strategy. It is a reminder that, as Saidiya Hartman writes in Scenes of Subjection, the violences of slavery were not only witnessed but orchestrated in a “pageantry of the trade.” In the sound work Naming the Money (2017), Himid voices an incantation of names, offering fragments of stories of one hundred Africans who moved through freedom, slavery, and servitude. The accompanying music, designed by Stawarska-Beavan, is a pastiche of genres, including Irish ballads and the jazz of John Coltrane. It reverberates within the exhibition’s final room, which is empty save for some speakers playing Himid’s recitation of names and a bike rack / smoking shelter (tobacco, like cotton, is a crop whose history intertwines with slavery). Himid has scrawled a provocation on the shelter: “Do you want an easy life?” The question circles back to the flags flying in the hallway, insisting that viewers supply their own answers.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is the Doris and Clarence Malo Professor of Art History at UC Berkeley and Adjunct Curator at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo. Her book on Louise Nevelson is forthcoming from Yale University Press.