Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

Rebuking the racist marketplace, the singer-songwriter’s new album combines therapy and protest.

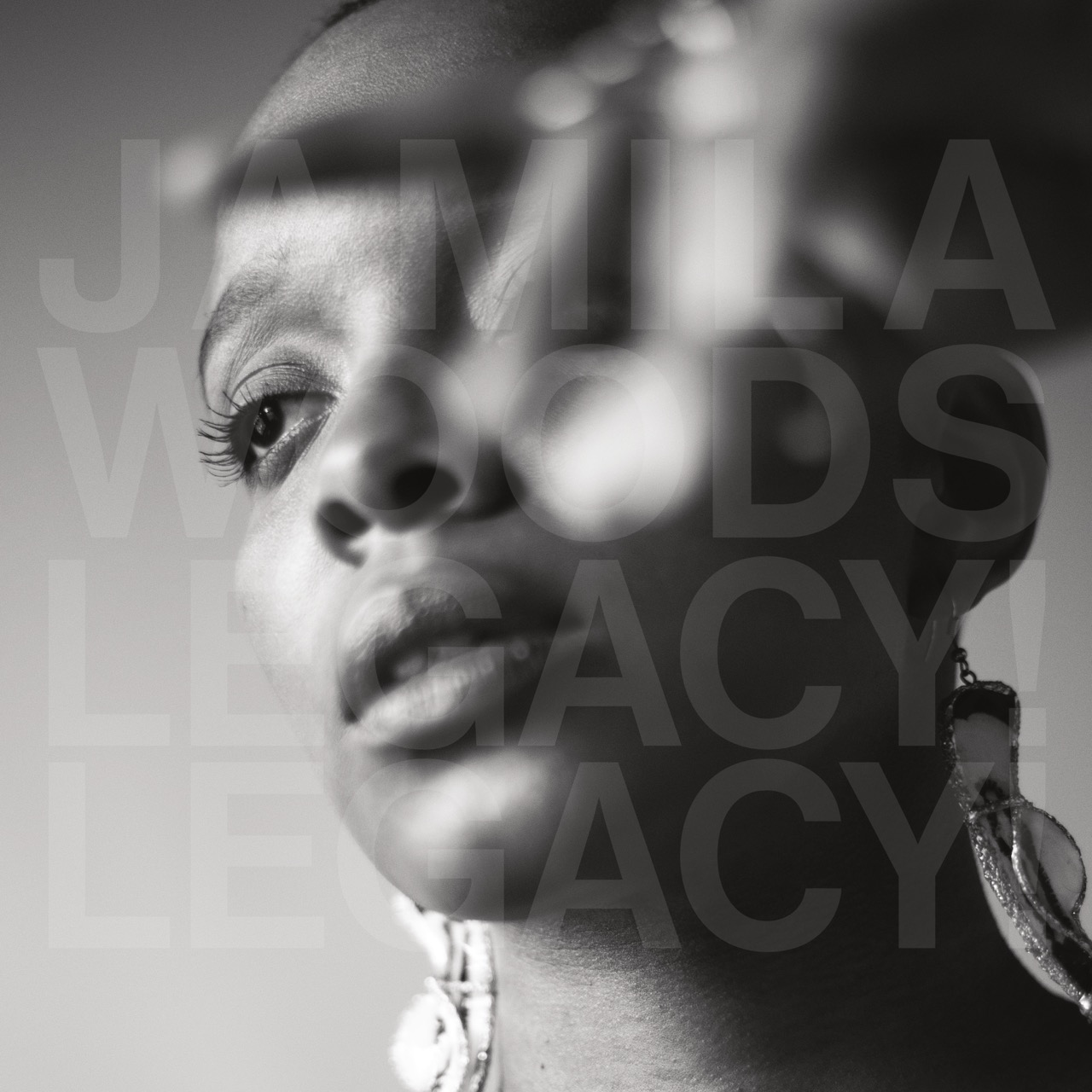

Legacy! Legacy!, by Jamila Woods, Jagjaguwar

• • •

When was the last time a musician from any pop genre tried to drum up attention for books? With her second album, Legacy! Legacy!, Chicago-based singer-songwriter Jamila Woods pays tribute to geniuses from a broad swath of creative fields, iconic figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Miles Davis, and Eartha Kitt. But even as she tips her hat to painters and performers, she repeatedly circles back to the idea of reading as a sacred act, a source of freedom and strength. On a song named after sci-fi author Octavia Butler, she advises, “Don’t ever let a textbook scare you”; later, she drives home the fact that literacy was once illegal for African Americans (“It used to be the worst crime / to write a line”). And in her spare but effective video for “Zora,” which she shared in the run-up to the album’s release, we see Woods and her band playing in a library filled with magnificent, ceiling-high bookshelves. Amid this lifetime’s supply of reading material, she intones, “You will never know everything, everything,” as if to remind her audience that even as we pursue truth, something of its essence remains elusive.

This is not a common approach in modern R & B—not even within the bohemian variety that used to get marketed as “neo-soul,” to which Woods shares an unmistakable kinship. Before Woods fully blossomed into her music career with her acclaimed debut, 2016’s Heavn, she was a published poet, and she’s kept one foot in her local literary scene by serving as the associate artistic director of Young Chicago Authors, an organization that takes hip-hop as the core of its pedagogy. Perhaps it’s her experience facilitating youth workshops on poetry and spoken word that has made her so adept at producing music that’s deeply informed by the past without ever seeming bookish. Her songs may be named after trailblazers, but the lyrics contain only glimmers of biography and are, for the most part, rooted in an urgent present tense. Without overselling its concept, Legacy! Legacy! emphasizes continuities between then and now, much as Butler did in her novels, and the message to listeners of color is clear: just as they suffered, you will suffer; just as they rose, you will rise.

Woods is traveling down a familiar path, one paved by artists like Erykah Badu and India.Arie, who infused turn-of-the-millennium black pop with a fresh, spiritualized Afrocentrism. A sizable chunk of Legacy! Legacy! centers on reclaiming the language of self-care and self-affirmation for the Black Lives Matter era, a mission fully in keeping with the songs on Heavn. This results in a few soggy love-yourself mantras (“Who gonna share my love for me with me?” she wonders on “Eartha”), but as in hip-hop—a genre that Woods occasionally invokes, with the help of the stellar young rappers Nitty Scott and Saba—it also takes the form of witty braggadocio: on the punchily cadenced “Giovanni,” a highlight inspired by the Nikki Giovanni poem “Ego Tripping,” Woods quips, “You might want to hold my comb when you find out what I’m made of.” She is at her most magnetic as an asserter of self, which may be why her discography so far has been remarkably light on odes to eros and romantic codependency, the fixations of mainstream R & B. Even when she’s hitting a more amorous note—the closest she gets on this album is the teasing “Frida”—she takes pains to contextualize black love within a history of oppression.

Combining elements of therapy and protest, Woods’s songs pivot on extended refrains that at times evoke the urgency of a rallying cry and at others induce a kind of bubble-bath calm. Her voice is the perfect bridge between these two moods; it’s hardly a virtuosic instrument, but R & B, despite being home to pop’s most Olympian singers, has always accommodated more intimate and idiosyncratic tones like hers. Woods has some of the tanginess of Badu and the sandpapery timbre of Macy Gray—sounds that lend themselves to a quirkier, more ironic delivery—and she makes plenty of room for that on Legacy! Legacy!. The album is immediately striking for its avoidance of the kind of coffee-shop earnestness that marred Heavn, and in its exhilarating second half she adopts a variety of male personas to sustain a harder-rocking, semi-psychedelic attack.

Part of that aggression stems from the subject matter. Woods has often highlighted the thrill of an insular, “for-us-by-us” mode of address; her breakout song on Heavn, “Blk Girl Soldier,” was squarely aimed at the community of women for which it’s named. But in the final stretch of Legacy! Legacy! the lyrics’ recurring addressee is the white listener, as Woods rebukes the racist marketplace in which black artists, past and present, have been forced to operate. Built on an ominous bassline, “Miles” balances anger and bravado by mixing abrasive textures with sweet melodic lines. Woods talk-sings on the sharply written verses, while on the woozy hook she points out, in the voice of the jazz legend, “I gave you the cool / I could do it in my sleep / seven days out of the week.” That formula is repeated on “Muddy,” a clash of crunching electric guitar and distorted vocals in which Woods speaks from the perspective of a musician who feels he’s been ripped off (“they can study my fingers / they can mirror my pose”), perhaps referencing Muddy Waters’s declaration that Mick Jagger stole his sound.

This half of the album must be one of the most direct and extended explorations of racial appropriation to ever make its way onto an R & B record. But while Woods uses these affronted male-genius egos as springboards for her social critiques, this is not where her arguments finally land. The penultimate song takes us back to the themes of love and literature. “Baldwin” runs through a litany of societal ills, from police brutality and gentrification to everyday microaggressions and white ignorance (“the books you ain’t read”), then raises the question of how interracial understanding can ever be achieved. “My friend James says I should love you anyway,” sings Woods to the white listener, and it’s a startling line, partly because it marks the first time the album has presented any of the singer’s cultural idols with a degree of skepticism. Where would this love come from, she seems to be asking Baldwin, and how could it be justified, given the facts at hand? Arriving at the end of such a vibrant album—one of the most satisfying in recent R & B—these questions open onto a void that Woods leaves tantalizingly unfilled.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.