Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

The work of Chinese poet Yi Lei arrives in a problematic translation.

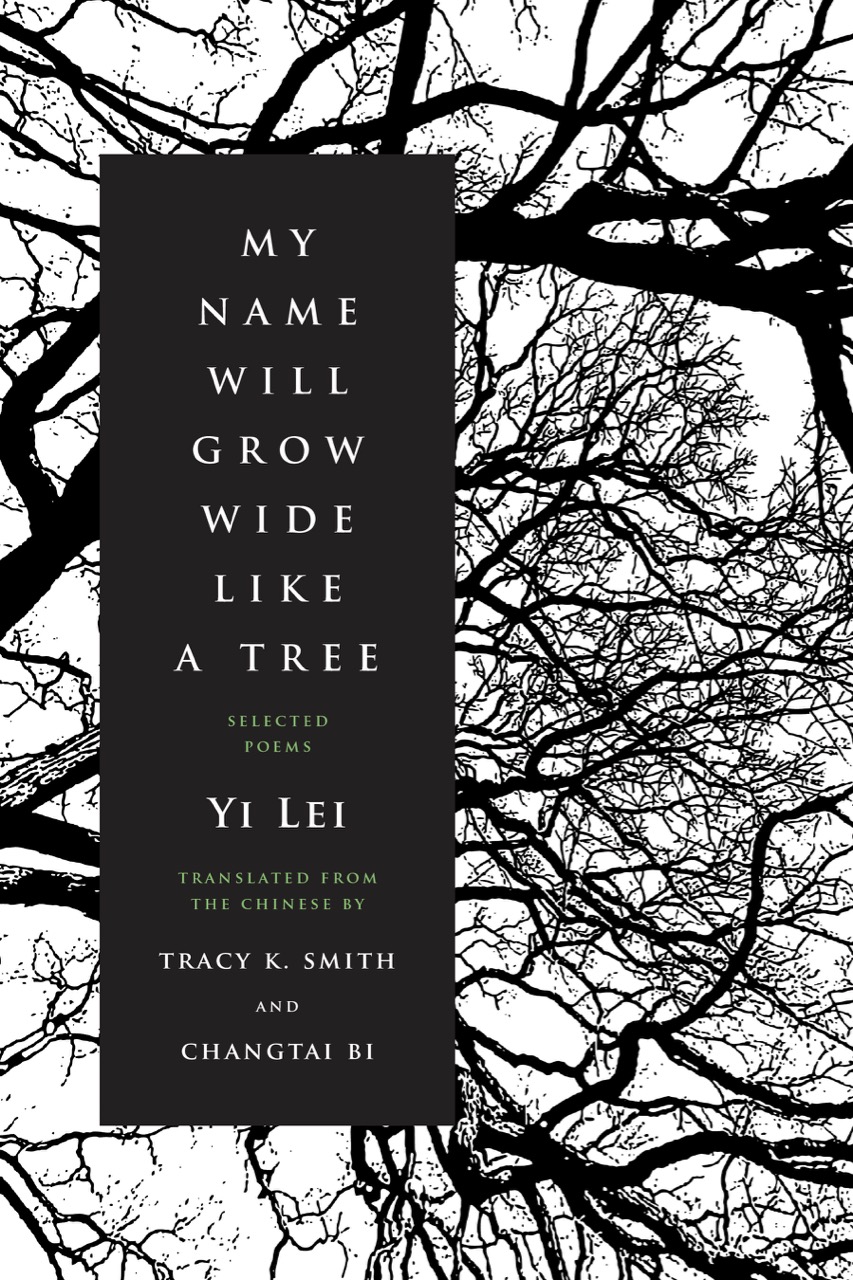

My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree: Selected Poems, by Yi Lei, translated by Tracy K. Smith and Changtai Bi, Graywolf Press, 133 pages, $17.99

• • •

For much of its millennia-long history, Chinese literature has tended to shy away from first-person disclosure. This was true even in the 1980s, a watershed decade that marked a departure from the propagandistic mandates of the Communist Party and opened up avenues for more individualistic and idiosyncratic forms of expression. For years, the most prominent poets of this period to reach a Western readership have been those associated with the Misty School, a collective of writers (including internationally celebrated ones like Bei Dao and Gu Cheng) who channeled the social turbulence of the nation with an opacity that helped them, at least initially, evade the censors. As several less widely heralded voices from this movement have made it into English translation in recent years, in no small part thanks to the extraordinary efforts of Zephyr Press, they have reinforced the idea of a literary renaissance whose output was rich in dreamlike imagery and metaphor but mostly devoid of direct autobiography. Reading these poems, you often feel like you’re seeing the speaker’s world through a deliberately fogged-up mirror.

This is the stage onto which Yi Lei—one of the few female Chinese poets to achieve notoriety in the ’80s—has belatedly arrived. She was not a Misty member, and it shows in the nakedly diaristic intimacy of her best verse. An anthology of translations by the American poet Tracy K. Smith and the Chinese-born academic Changtai Bi, presented alongside Yi Lei’s original texts, My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree reads like one long, insistent song of the self. Written after decades of suppression had discouraged Chinese artists from getting too personal, lest they be accused of bourgeois indulgence or counterrevolutionary sentiment, these merciless excavations of the poet’s soul feel like a real breakthrough.

In the most famous of her poems, the fourteen-part sequence “A Single Woman’s Bedroom” (1986), Yi Lei’s independent spirit collides with her interrogation of the very idea of personhood. Introducing herself as if she were the star of a movie or the headliner in a gossip magazine, she opens with a string of haughty boasts that serve as a caution to the reader: “She is one and many, / A multitude flashing on, then off, / Watching out from the blank / Of her face.” The poet’s gaze is so steadfastly inward that it’s surprising when, at the end of each section, she addresses a largely undescribed lover who has for whatever reason declined to come and live with her, a refrain made all the more resonant by the knowledge that cohabitation out of wedlock was illegal in China at the time.

In this and other poems, Yi Lei vacillates between a kind of gleeful self-aggrandizement and confessions of dejection and defeat. From moment to moment, as she maps the contours of her capacious identity—one adjective she repeatedly uses for herself is “boundless”—she sways from a forthright first person to a clinically observant third person, at times regarding her image reflected in mirrors as well as her own photographs and paintings. The impression is that of a self-portraitist trying out every tool at her disposal—and ending up vaguely dissatisfied with all of them. In one disarming passage in “A Single Woman’s Bedroom,” she describes her ritual of drawing a curtain on the darkness of her room, explaining that the barrier “seals in my joy” and “holds the razor out of reach.” In another part of the same poem, she imagines pure consciousness as a country unto itself, for which she hopes to be granted a visa. Poets who operate primarily in a confessional mode tend to mine and ravage their psyches; few make a virtue of treating their minds as treasure, and it’s thrilling to encounter the ferocity with which Yi Lei protects hers.

The braggadocio in “A Single Woman’s Bedroom” is characteristic of a lot of Yi Lei’s work, and yet the poem climaxes thuddingly, with the line “What I hate most is the person I’ve become.” Such admissions of self-loathing crop up again and again in the book, though the cumulative effect is far from depressing, a testament to how lovingly the poems situate the writer’s anxieties and suicidal thoughts within a paradoxical vision of sensual delight.

When Yi Lei allows herself to surrender to pleasure, the results are frequently ecstatic, and her erotic verse is among the most vivid—and genuinely sexy—in modern Chinese literature. In “The Nude,” her penchant for bragging turns carnal—“The curtain of my hair / Announces my breasts”—and the sensations of orgasm take on an absurdly cosmic power, becoming the “dexterous gold watch of the universe / On which one minute can straddle / A hundred years.” Elsewhere, Yi Lei grants herself reprieve from the tempestuousness of her insular private life, proving a sharp-eyed observer of the outside world. It seems inevitable that she would dedicate a whole poem to Walt Whitman, another bard of self-regard who also nursed a voracious hunger for nature.

These twin qualities can be found in Smith’s work, too, which would seem to make the Pulitzer Prize winner—one of the preeminent American poets of her generation—an ideal choice to shepherd Yi Lei’s legacy into English. But herein lies a problem. Saturated with Smith’s voice and propelled by her unerring ear for catchy bits of diction, these translations often feel more rewarding to read as a fresh batch of Smith’s own poems than as interpretations of pieces written on the other side of the world decades ago. Smith takes pains to be transparent about this in her introduction, explaining the years-long process by which she and Bi reenvisioned the poems, their goal of revising the work so that it would resonate more deeply with American readers, and how they obtained Yi Lei’s approval before she passed away suddenly in 2018. Smith even makes it a point to demonstrate the kinds of liberties she took by comparing a snippet of a more literal translation of one poem with her very different final version.

Still, it’s unfortunate that the always-fraught issue of translation will be distracting for any reader, like myself, who is proficient enough in both languages to recognize the glaring chasms in style, tone, and content. There exists an understandable but faulty assumption that certain languages are so distant from one another that translation requires a high degree of artistic license. But words still mean what they do. In many instances throughout the book, phrases, images, and metaphors that Smith and Bi could have brought into English with relative ease are needlessly contorted or jettisoned altogether, while elements that do not exist in the less flowery originals are allowed to proliferate like weeds. Considering how crucial and lasting first impressions can be when transporting literature across cultures, it’s a delicate matter, one that calls to mind the recent controversy ignited by Deborah Smith’s translations of the Korean novelist Han Kang, which some bilingual critics have deemed cavalierly loose. I emerged from My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree in a state of confusion, grateful for having been introduced to Yi Lei’s intoxicating voice and for Smith’s undeniably supple musicality, but concerned about the false conclusions that English-only readers will draw from these willfully unfaithful renditions.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, NPR Music, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.