4 Columns

4 Columns

In this week’s missive, we consider states of insomnia and drugged unconsciousness, the magnificence of dreams, and what it means to sleep through a revolution.

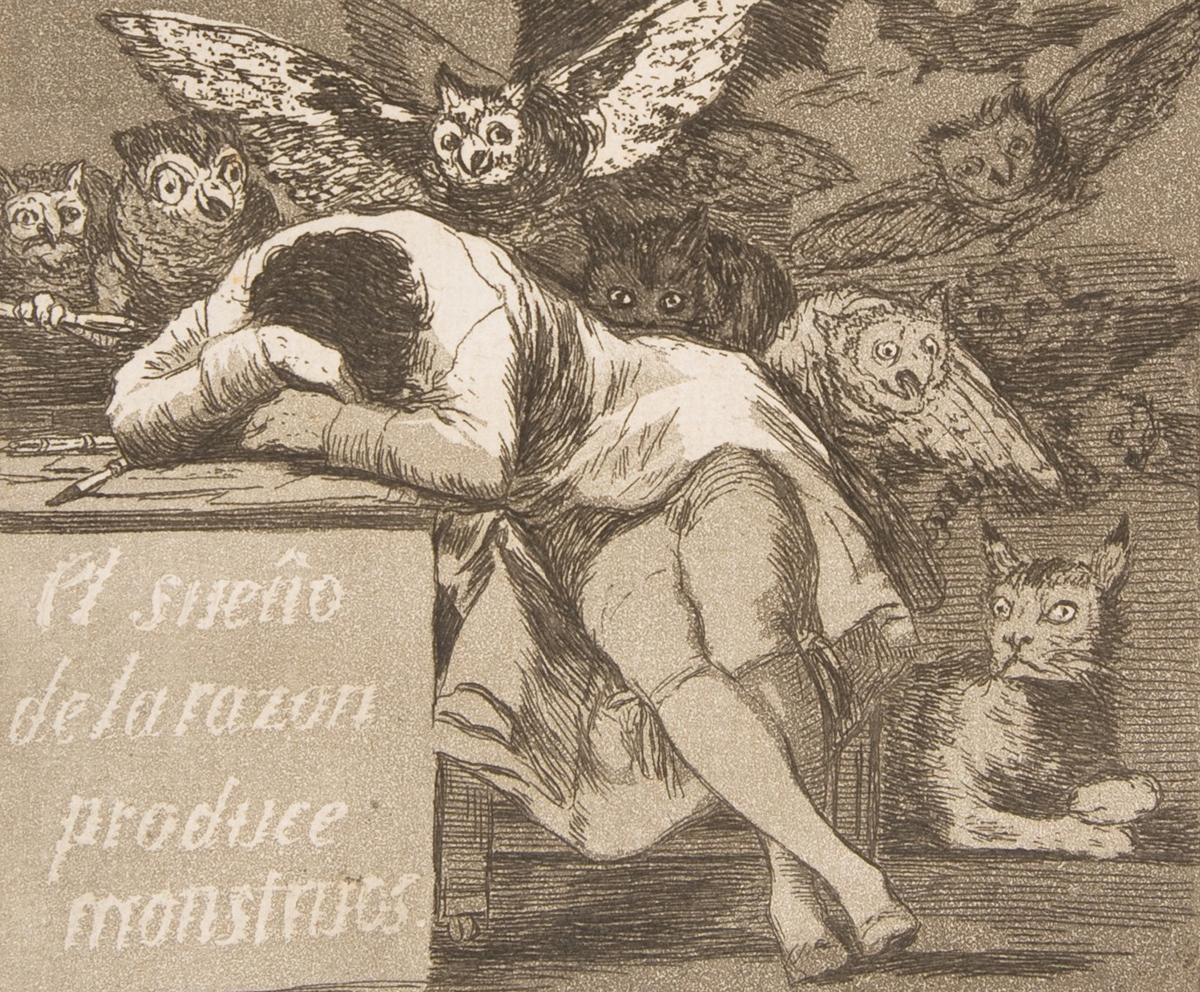

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, The sleep of reason produces monsters, plate 43 from “Los Caprichos.” Etching, aquatint, 8 3/8 × 5 15/16 inches. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the event of a heat wave, public health workers recommend abstaining from napping. In the heat of the night, it can feel impossible to sleep, so it’s best to starve the body of rest, in hope of forcing it to fall asleep later, helplessly, out of desperation.

But it’s not so easy to trick sleep in this way. It’s so hard to resist, especially when it feels imperative to pull yourself out of its fall; and it’s so hard to conjure, especially when you most desire it. The heat makes you delirious, the heat keeps you from sleeping, the lack of sleep stretches on and on, the lack of sleep catalyzes the delirium, and the cycle repeats. The world is overheating, it’s becoming hotter and hotter—the afternoons are so heavy-lidded, the nights so frantic for lack of air—what will happen to our sleep? Will the next plague be insomnia, blanketing a world “sinking irrevocably into the quicksand of forgetfulness,” as Gabriel García Márquez wrote of another sleep-deprived world?

For explication, and for solace, let us turn to a special vein of criticism that has recurred throughout the pages of 4Columns: a criticism obsessed with the nocturnal hours when we should be sleeping and that seeks to discover what happens there.

Insomnia, by Marina Benjamin

Reviewed by Brian Dillon

The hellish (if, sometimes, manically seductive) phenomenon of insomnia has been carefully considered in the pages of 4Columns by critics like Brian Dillon, in his review of the aptly and simply titled Insomnia (2018). Author Marina Benjamin offers no self-help solutions, though, like so many recent nonfiction titles dedicated to the topic. “Benjamin’s approach to her subject is deliberately at odds with the current popular literature on sleep and its discontents,” Dillon says. Rather, she “is more interested in the experience of sleeplessness than she is in reasons or remedies . . . She describes that experience with a strange precision that verges at times on the hallucinatory; in fact, stranded between these two poles, between clarity and chimera, is where we may find the insomniac.” Benjamin proves fascinated by her own sleeplessness; she strives to validate it as a site of peculiar, electric knowledge inaccessible to the rested. For her, “the night brain is akin to a jellyfish: ‘luminescent, awake, alive.’ ”

The Shapeless Unease, by Samantha Harvey

Reviewed by David O’Neill

No such consolation is offered in Samantha Harvey’s memoir of insomnia, The Shapeless Unease (2020), reviewed for 4Columns by David O’Neill. For Harvey, sleeplessness is not mythically inspiring, but a torturous state that she feels transforms her into a wild animal trapped in a cage: “she goes ‘feral’ many nights,” O’Neill describes, “pulling out her hair, pacing, screaming, and smashing her head against the wall. In the morning, she emerges feeling not tired, but ‘assaulted.’ ” Like Benjamin’s Insomnia, though, Harvey’s book offers no solutions, no guidance—for nothing has worked for this author, not the sanitized practices of “sleep hygiene,” not drugs, nothing. The sleeplessness perpetuates itself, insatiable: “a fear of insomnia is a symptom of insomnia that soon becomes its cause.”

Charlize Theron as Marlo in Tully. Courtesy Focus Features.

Tully, by Jason Reitman and Diablo Cody

Reviewed by Michelle Orange

Derangement from lack of sleep is also captured in Jason Reitman and Diablo Cody’s 2018 film Tully, reviewed by Michelle Orange. Tully is the story of an overwhelmed mother, Marlo (played by Charlize Theron): “a woman whom motherhood seems to have placed beside herself,” Orange writes. The film suggests Marlo “is miserable because she is tired”; pregnant with a third, unplanned baby, she is “a figure of suffering and isolation,” not least because, especially once her new child is born, she is plunged into that universal state of motherhood: sleeplessness. A night nurse is called in to her aid, and through her, Marlo finally has access to sleep again—or so it seems. The relieved mother’s world becomes filled with rainbow hues—but are these cheery colors granted by good rest? Or do they hint at the untrustworthiness of the insomnia-addled mind?

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh

Reviewed by Brian Dillon

Escaping the pains of unremitting wakefulness described above (or maybe just the disappointments of consciousness, in general) is what motivates Ottessa Moshfegh’s popular 2018 novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation. In advance of its publication, the author described it as “a book about putting yourself to sleep in an effort to heal”—in this case, with synthetic drugs, which Moshfegh’s anonymous protagonist leans on heavily to stop being awake. Dillon also wrote about this book, which is perhaps diametrically opposed to Benjamin’s Insomnia: “This is certainly a book about sleep,” he writes, “if that is the word for the narcotized void into which Moshfegh’s anonymous protagonist slips on almost every other page. Rarely has a novel’s narrator felt less alive, less alert, less present in her own tale even as it spins. She’s not a narcoleptic, but the elective opposite of an insomniac—‘I was more of a somniac. A somnophile.’ ” The inert protagonist is “convinced . . . that if she can burrow even further into the void, she will emerge on the other side, if not brightened then at least, and at last, able to feel.”

Clockwise, left to right: Gwendoline Christie as Titania, David Moorst as Puck, Oliver Chris as Oberon, Hammed Animashaun as Bottom, and Ryan Bawa in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Courtesy National Theatre. Photo: Perou.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Nicholas Hytner

for Bridge Theatre

Reviewed by David Cote

Insomnia and drug-induced slumber have in common a lack of dreams, the most thrilling part of being asleep. Approximately one-third of our lives is spent dreaming—such an enormous portion of our time on Earth is experienced as nocturnal hallucination. The great artwork of such phantasmata, of course, is Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a fantasy in which “night is the kingdom of the fairies”; the characters are all unified in their sleep, repeatedly entering and exiting slumber, each time finding themselves changed, confused. During last year’s COVID shutdown orders, when theaters were darkened, David Cote reviewed a Bridge Theatre production of the play that streamed online for sheltering-at-home viewing. “The play asks whether anyone—a sprite, a mortal, a theatergoer—can believe what they see, not sure if they’re awake or dreaming,” Cote writes. “This Dream makes for a charming, elevating escape as we wait for the world to awaken.”

Betty Boop: Snow White.

Betty Boop: Snow White, directed by Dave Fleischer

Reviewed by Emily LaBarge

Emily LaBarge’s deep dive into Dave Fleischer’s 1933 animated short Betty Boop: Snow White also dissolves into dreams of delirium. The film itself hinges on the titular’s character own deep sleep: Betty Boop has been cursed by the evil witch to take the most profound of siestas while frozen in a block of ice. In her explication of the film, LaBarge turns to that noted philosopher of sleep, Walter Benjamin, for whom “creations like Mickey Mouse, or Betty Boop, are figures, emanations of ‘the collective dream,’ ” she writes. LaBarge thus encounters a sort of utopian solace in this dreamy Betty Boop: “in the present moment of fatigue, like the weary population Benjamin speaks of in ‘Experience and Poverty’—written the year Betty Boop: Snow White was made—‘to whom the purpose of existence seems to have been reduced to the most distant vanishing point of an endless horizon,’ I like to think of how we might all live and sleep and dream together, finally not as apart or indifferent as we imagine.”

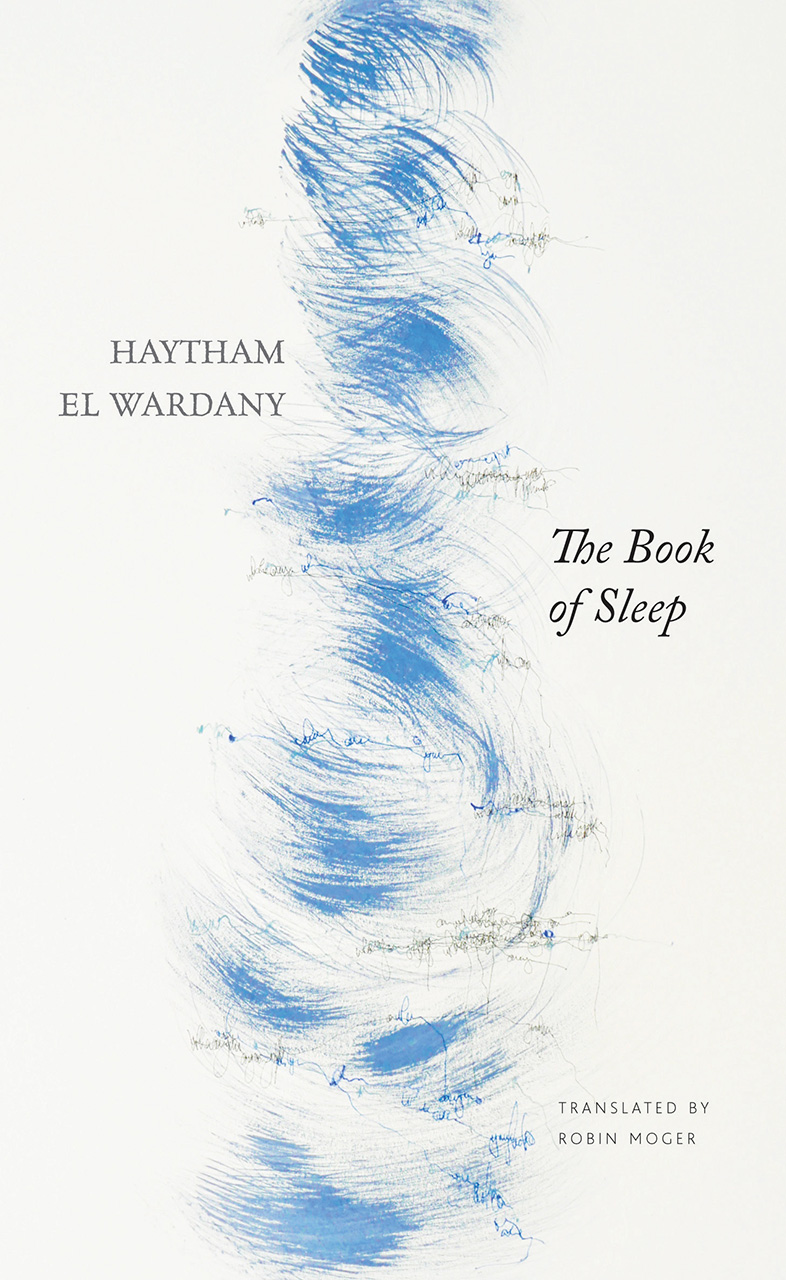

The Book of Sleep, by Haytham El Wardany

Reviewed by Ania Szremski

The idea of the collective dream—made possible, of course, only in the fact of collective sleep—also appears in Egyptian author Haytham El Wardany’s 2020 The Book of Sleep, reviewed by Ania Szremski. El Wardany’s hallucinatory, genre-fluid text is perhaps the most resounding argument for sleep and its many potentials that can be plucked from the 4Columns archives. “But isn’t sleep the antithesis to the vigilance that protest demands? A cowardly withdrawal from courageous action?” Szremski wonders. “No! The Book of Sleep is the clearest rebuke (that the rebuke can be so clear while the text is so slippery is one of its drowsy mysteries) against the disdain for rest. ‘The self which does not sleep is a neurotic self, plagued by itself. The group that does not sleep is willful and proud, unable to alter reality because it exists cut off from it.’ It is only in sleep, El Wardany argues, that an arrangement with reality can be rebrokered. And if we do not sleep, the hopeful awakening will never come.”