4 Columns

4 Columns

This week, we coax out of archival hibernation reviews that reveal the human-and-bear relationship status: it’s complicated.

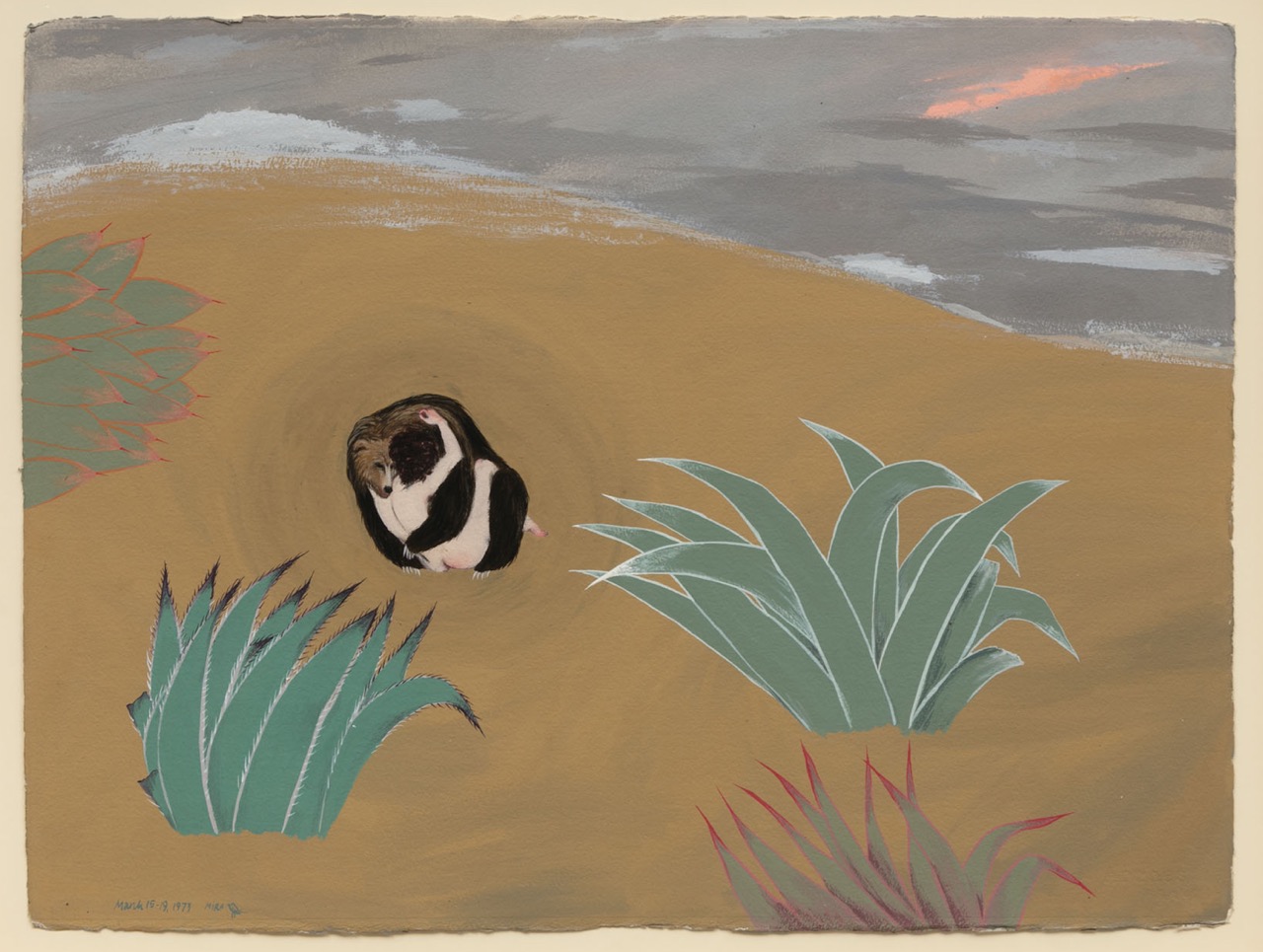

Mira Schor, Bear Triptych (Part I), 1972. Gouache on Arches paper, 22 × 30 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

What sound does a bear make?

It’s not an obvious question, depending on what language you speak; not all languages are rich in bear. Some are, though, like Romanian, in which you can advise someone to “fuck off” by telling them to “plimb ursul,” or “go walk a bear.” A Google search for bear sounds, in English, reveals these results: “huff, chomp, woof, growl, and/or bark.” In Romanian, the utterance is more specific, more poetic; in it, the bear goes moar, moar . . . which sounds something like death, death. Which is, presumably, the fate of those who get close enough to hear it.

Bears clearly possess a robust stronghold in the Romanian imaginary, as this is a nation in which bears abound and often stir trouble. But they are a universally mysterious and multivalent symbol. Even the 4Columns archives testify to an unlikely ursine influence on the contemporary cultural landscape. What is it about the bear that so fascinates, so enchants?

• • •

BEARS ARE TERRIFYING

Part of their thrall lies in the fact, of course, that bears are terrifying—despite their roly-poly appearance and dopey antics, they wield enormous destructive power. The great cultural artifact of bear-fascination bleeding into bear-terror is Werner Herzog’s 2005 film Grizzly Man, a posthumous account of terminal “bear enthusiast” Timothy Treadwell, who, along with his girlfriend Amie Huguenard, was fatally attacked by a brown bear in 2003. But we can now add to Herzog’s document a perhaps even more formidable account of Ursidae obliteration, all the more terrible because the story comes firsthand, from a victim who lived: French anthropologist Nastassja Martin. Her best-selling In the Eye of the Wild, published in English in 2021, vividly describes her encounter with a Kamchatka brown bear in Siberia who swiped away her jaw. In their review of the book for 4Columns, Megan Milks explains that even “as Martin stretches to find meaning for her ordeal, she rejects the compulsion to reduce it to symbol. In the West, she notes, the bear might represent strength and courage; wildness; love; power; retreat. Her disfigurement: sacrifice. . . . This tug-of-war around meaning-making and meaning-refusal becomes the central tension in the book.”

• • •

AND SO WE HUNT THEM . . .

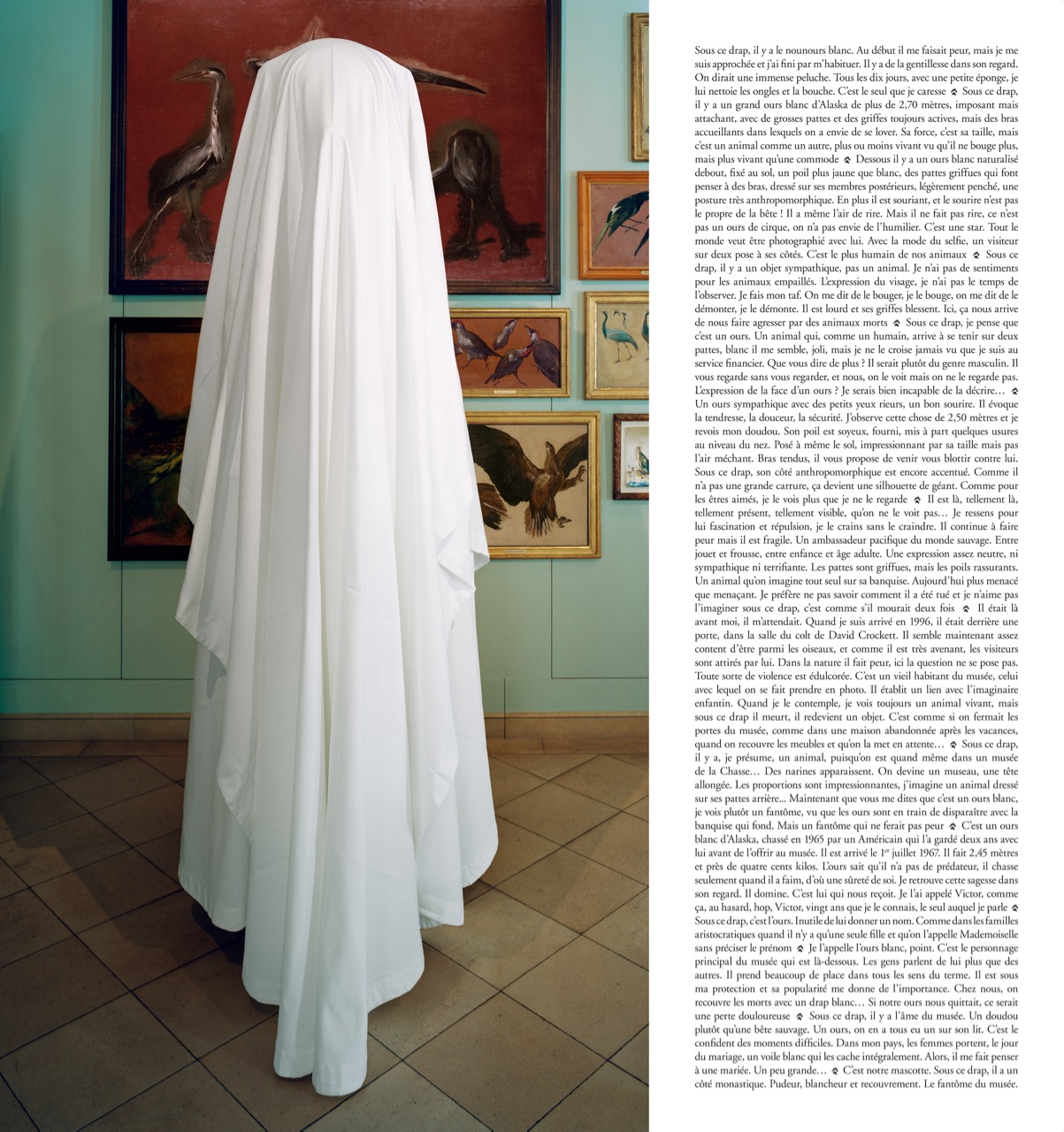

Indeed, bears resist easy symbolic reduction throughout our archives, even when it comes to the stuffed bear–as-trophy—one of the more ubiquitous ursine icons in Western culture. Artist Sophie Calle knew that human fear gives rise to bloody attempts at natural dominion when she covered a taxidermized polar bear with a sheet, turning him into a child’s vision of a ghost, in her 2018 exhibition at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris, reviewed by Nico Israel; artist Nicholas Galanin knew it when he attached a polar bear rug to a pole in his exhibition earlier this summer at Peter Blum Gallery in New York City, reviewed by Aruna D’Souza.

Sophie Calle, L’ours (The Bear), 2017. Diptych. © Sophie Calle / ADAGP.

Just like Martin refused obvious meaning-making, so too do these two contemporary artists. Calle’s installation was accompanied by a long text (available in French in Israel’s review) in which she describes how her fear of the great white bear transferred into love and longing, in which she describes how this ferocious beast was transformed, through the hunt and through museological exhibition, into a ridiculous mascot (but of what?): “He is there, so there, so present, so visible, that you don’t see him . . . I feel for him fascination and repulsion, I fear him without fear . . .”

Nicholas Galanin, White Flag, 2022. Trimmed polar bear rug and wood. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery.

Nor is Galanin’s bear an uncomplicated token of Man’s triumph over Nature. “The hide, a trophy of an early twentieth-century white sport hunter, clings to its wooden mast, grasping it by tooth and claw as its body stretches out, as if whipped by a strong wind,” D’Souza writes. “The bear—what is left of it—looks either like it is desperately hanging on for dear life or determinedly seizing its prey. It is at once an image of vulnerability and precarity and of tenacity and strength—an apt description of the condition of both polar bears and Indigenous peoples whose ties to the land are central to their cultures and survival in this era of rapid and devastating climate change. Ecocide is also genocide. But even though the title of the piece refers to a battlefield symbol of surrender, the fierceness of the polar bear’s expression belies quiet capitulation.”

• • •

. . . OR WE MAKE THEM DANCE . . .

Man doesn’t only try to quell his fears by killing them (bear being, among other things, the embodiment of fears as existential as they are literal), but also by domesticating them, making them dance according to his whims, making them cute. Polish journalist Witold Szabłowski provides a heartrending account of the keepers and trainers of dancing bears in Eastern Europe, especially Bulgaria, in his 2018 Dancing Bears: True Stories of People Nostalgic for Life Under Tyranny. And he notes what happened to the captive animals when the EU prohibited their exhibition in 2007 and sentenced them to “freedom” in a sanctuary—the bears, pained and confused by their new circumstances, desperately tried to keep on dancing. One such dancing bear is the central figure of Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear, published in Susan Bernofsky’s English translation in 2016, reviewed for 4Columns also by Milks, our chief critic of bear literature. The novel imagines a prehistory to the story of Knut, “the young polar bear rejected by his mother and raised by a human surrogate in the Berlin Zoo” who suddenly died in 2011 of a human-borne neurological disease. “Each of the book’s three chapters chronicles the life of one polar bear . . . We begin with Knut’s grandmother, a former USSR circus performer turned memoirist whose chronicling of her past quickly gets disrupted by her present. We then move to Knut’s mother, Tosca, a dancing bear who takes on the even more unusual authorial task of writing her trainer’s life story in what becomes a joint autobiography. The final portion of the book, Knut’s chapter, begins as biography.”

• • •

. . . WHILE WE ALSO MOURN THEM . . . AND DESIRE THEM

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 (installation view). Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Knut’s tragic fate at the Berlin Zoo brings us to another major ursine theme evinced in the archives of 4Columns: the polar bear as a lamentable symbol of loss, of precarity, of human-authored wreckage upon the natural world in our quest to conquer it. A trapped polar bear dolefully figures in John Akomfrah’s three-channel video installation Vertigo Sea (2015), reviewed by Sukhdev Sandhu; the young protagonist of Lisa Hsiao Chen’s debut novel, Activities of Daily Living (2022), also reviewed by Sandhu, is haunted throughout the book by a video clip of a starving polar bear she forces herself to watch over and over again on her laptop.

But fear and mourning can also give rise to a very different type of feeling: desire, an ache for touch, for togetherness. We fear the bear, we want to kill the bear, we lament the bear, we want to lie with the bear. Szabłowski gives an account from a Bulgarian bear keeper about how his audiences “wanted the bear to massage and heal them.” In this vein, we mustn’t forget the lasting popularity of bear-shifter smutty romances, or especially Marian Engel’s 1976 erotic novel Bear, which resurfaced into virality last summer. Mira Schor’s 1972 paintings Bear Triptych, extolled in Johanna Fateman’s 2019 review of an exhibition of the artist’s early work at Lyles & King, unsettle with their images of tender (yet menacing) bear-human coitus. They perhaps prefigure Engel’s own fantasy of sex with a bear, complete with descriptions of the bear’s “fat, freckled, pink and black tongue . . . It licked. It rasped, to a degree. It probed. It felt very warm and good and strange.”

Mira Schor, Bear Triptych (Part III), 1973. Gouache on Arches paper, 22 × 30 inches. Image courtesy the artist and Lyles & King.

• • •

BUT WHAT DOES THE BEAR FEEL?

Courtesy US National Park Service.

Amid everything we have projected upon the bear in this affect-laden reading list, what of the bear himself? What is he thinking, or feeling, or desiring? It’s difficult to know—bear sentience is, perhaps for obvious reasons, woefully understudied compared to the animal’s less-fearsome mammalian counterparts. But let us close with a remembrance of how scientists have observed how bears in the wild often have a habit of sitting still for hours on the grass, staring out at a vista or a river, leading to a popular notion that bears may have an abiding appreciation for natural beauty. They are caught up in their own love affair—not with us, but with the sublime. While we humans are so frantically vesting them with all sorts of meanings and desires, the bears themselves want nothing more than to be left alone to admire the sunset.