Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Painting from photographs, an artist works through memory, history,

and trauma.

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery.

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, curated by Dorothy Moss, National Portrait Gallery, Eighth and G Streets NW, Washington, DC, through May 30, 2022

• • •

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, on view at the National Portrait Gallery, is the first major East Coast presentation of this Chinese-born American painter and the first-ever solo exhibition of an Asian American woman at the museum. It comes tragically late in Liu’s career; she died of pancreatic cancer less than three weeks before Portraits of Promised Lands opened at the end of August 2021. Her belated reception in this part of the country says more, it would seem, about the myopia of the East Coast art world than about her visibility or impact. She was an important and inspiring presence in California, where she arrived in 1984 to pursue graduate work at the University of California, San Diego, under the guidance of Allan Kaprow and Moira Roth; afterward, she took a position at Mills College in Oakland, where she taught for twenty-four years. She showed often on the West Coast, as well as in China, and was the subject of a significant retrospective organized by the Oakland Museum in 2013. She was respected among her artistic peers—Carrie Mae Weems, Mel Chin, Lava Thomas, and Judy Chicago—as well as younger generations of artists—Stephanie Syjuco, Liu Xiaodong, and Amy Sherald—as is made clear by the tributes from these and others included at the end of the handsome exhibition catalog.

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery.

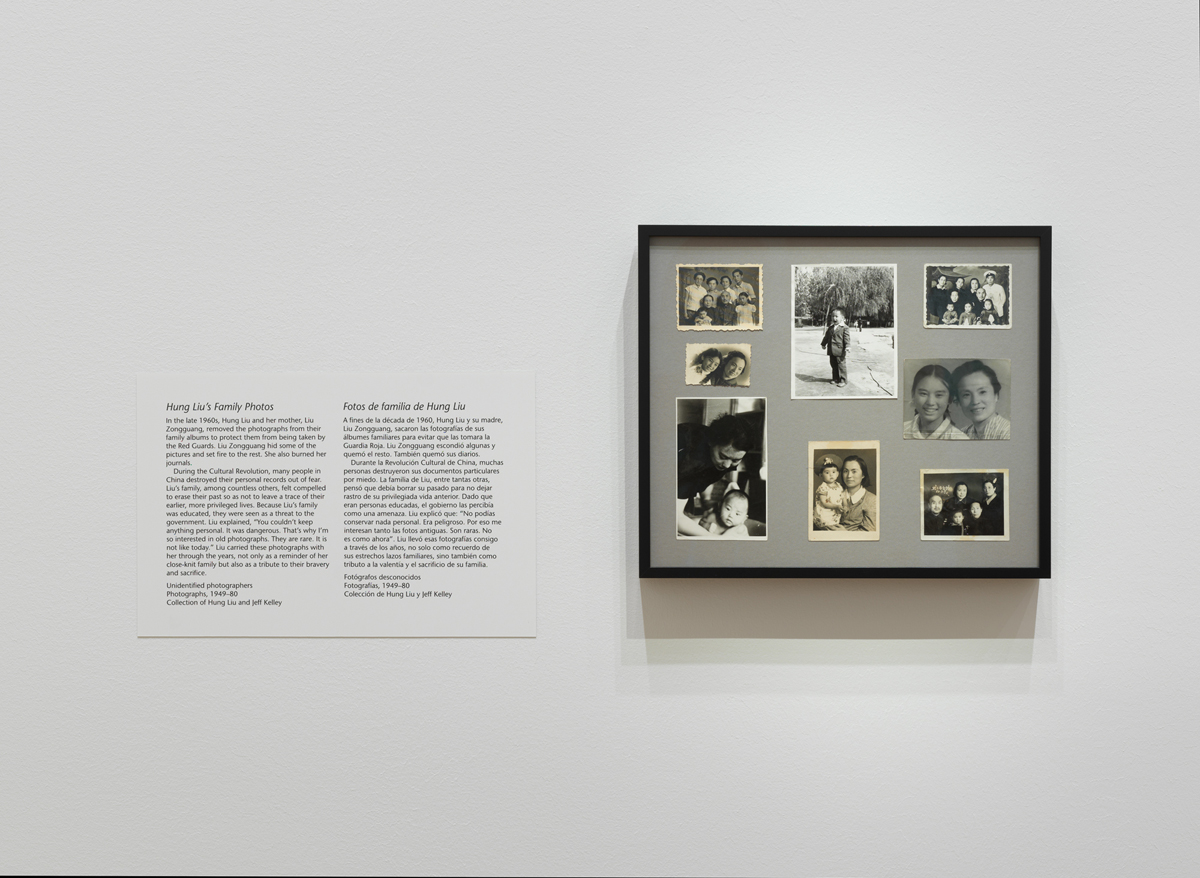

Borne of her early experience of war and famine (her father, who fought for Chiang Kai-shek’s army, was imprisoned for most of her life) and then of the Cultural Revolution (when she was relocated and forced into agrarian labor along with millions of others), Liu’s painted explorations of history, memory, and trauma convey suffering, but also the capacity for survival, and even the hope, that allow people to endure the unendurable. She does this by mining the emotional resonance of photography (the medium) and the photograph (the material object). During the Cultural Revolution, like many of those from middle-class, educated families, Liu and her mother destroyed their photo albums to erase evidence of their privilege and lineage in case they were discovered by the Red Guards, saving only a very few pictures. These treasured family artifacts, along with found images, reproductions in history books, and so on, were at the center of her work for all of her forty-odd-year career. But she was aware of photography’s limits, too—the way it lets us record and witness the lives of those who might otherwise be forgotten, but only imperfectly. Over and over in Liu’s practice we are reminded that though the camera has the capacity to confirm the existence of those it documents, its product does not adhere to the vagaries of memory or to how we recall people not in their mere appearance but via fragments and associations, as dissolving images that somehow, paradoxically, endure in our consciousness.

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery. Pictured, far left: Hung Liu, The Botanist, 2013. Pictured, far right: Hung Liu, Father’s Day, 1994.

In The Botanist (2013), Liu’s grandfather, Liu Weihua, stands just off-center of the 96-by-54-inch canvas, posing with an air of formality, wearing an elegant black robe. But while his figure has the look of being copied from an old photograph, Liu’s brushwork and handling of pigment tell a much more complete and vivid story than any photo could: she renders his face in hazy, impastoed strokes, as if she cannot quite remember what he looked like; she enhaloes him with images of plants and flowers that refer to his scholarly research but seem to hover and float and stick to the surface instead of nestling into his photographic space; she applies linseed oil onto the surface so that rivulets of pigment run down, unfixing form as they do. (These linseed drips, a signature feature of Liu’s style, take on different metaphorical meanings; in addition to evoking the effects of memory, Liu has also spoken of them as a means “to wash my subjects of their otherness and reveal them as dignified, even mythic figures . . .”) Sometimes she uses shaped canvases, as with her 1994 Father’s Day, based on a photograph taken that year during her reunion with her father at a labor camp in China, where he had been held for decades. (Liu and her family had assumed he had died sometime shortly after 1948.) The size of the canvas (54 by 72 inches), its sculptural form, and the architectural fragment that hovers on the wall to the right of Liu and her father, as if the space in which they stand has suddenly begun to materialize: all these qualities convey the monumentality of the moment.

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery. Pictured, left: Hung Liu, Refugee: Woman and Children, 2000.

The exhibition is hung thematically rather than chronologically, emphasizing recurrent ideas in her oeuvre: family, gender, refugees, and, after 2015, Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era photographs of migrants. But none of these categories are particularly distinct—and purposefully so. Her family are refugees, and, as is made abundantly clear in her paintings, refugees, no matter what the particularities of their circumstances, share a kinship that spans generations and geographies. Her predilection for seeing her own experience in others’ is apparent in her images of mothers with their children, whose situations mirror her own mother’s desperate flight from violence with two children in tow. Refugee: Woman and Children (2000) is a large-scale work based on a historical photo of a woman surrounded by two baskets, each holding a distressed baby. Liu, having heard her mother’s account of what she saw on her own journey to safety, understood the source image as depicting a woman forced to sell her children in order for all of them to survive. Liu surrounds them with symbols of protection and benediction: a crane, a series of Buddhas, a lotus flower. The painting becomes, in a sense, a shrine, a claiming of this nameless woman as an ancestor.

Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, installation view. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery. Pictured, far left: Hung Liu, Migrant Mother: Mealtime, 2016.

There is a danger in an exhibition like this of imagining the refugee-artist’s place of origin as one of unrelenting oppression, and her destination as one of uncompromised freedom—the latter an untenable idealism, given how unequally freedom is conferred in this country. Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands stops just short of falling into this trap, in part thanks to the inclusion of a series based on her research into Lange’s documentation of migratory farm workers. In speaking of the work, Liu quite pointedly refers to the poor white, Black, and Mexican subjects of Lange’s images as “peasants,” the term applied to those with whom she toiled in the fields during her ideological reeducation in Maoist China. The echo between contexts is apparent when looking at Refugee: Opera (2001)—a painting of a Chinese woman breastfeeding her child—and Migrant Mother: Mealtime (2016), after one of Lange’s iconic photos, in which it is not the empty breast but an empty plate in the foreground that signals the pathos. In both compositions, the world-weary women fill the left-hand side of the canvas, with their babies on their laps canted toward the right, and a massing (of people, in the first case, and of distant landscape features, in the second) in the upper right corner. Whatever the historical distance between them, these two women suffer together. In both theme and formal approach, the rhyming functions as an effective reminder that while for some, the US is a refuge, for others, it is and always has been an inhospitable, even impossible, place.

Aruna D’Souza is currently Edmond J. Safra Visiting Professor at the National Gallery of Art and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. A forthcoming collection of the writings of Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames & Hudson), which she edited, will be released in March 2022. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.