Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The painter’s lush oil portraits explore the work of empathy.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Under-Song for a Cipher, installation view. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio. Image courtesy New Museum.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Under-Song for a Cipher, the New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through September 3, 2017

• • •

His early twentieth-century admirers used to praise Cézanne for being able to paint his wife like he painted an apple—for turning her into a pure pretext for his formal and optical investigations. What underpinned this assessment was the idea that for less radical artists, portraiture (at least in its Western, post-Renaissance incarnations) is an act of empathy—that the sitter’s humanity is an essential component of the depiction, as essential as the canvas and paint that give it physical presence. Cézanne’s monstrous genius, as described by his most ardent fans, was that he rejected this convention of the genre: his devotion to questions of form (color, shape, line, composition—purely pictorial things) was such that he was willing to empty out his sitter’s very being, and turn existence into mere thingness.

British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s brilliance—and I use that word advisedly, for this show is indeed brilliant—is that she is able to do exactly the reverse: to draw the viewer into an emotional connection with a someone who isn’t a someone at all, to coax us to feel empathy for a non-being, an illusion, a mere representation produced by a few strokes of goop on cloth. To take those purely pictorial things and conjure humanity out of them.

The seventeen canvases that make up Under-Song for a Cipher, the 2013 Turner Prize finalist’s installation at the New Museum, are unmistakably portraits. All but one created in the first months of 2017, these lush oils on linen, the most traditional of media, are painted in bravura brushstrokes and stick to a relatively somber palette. They mine the history of their genre in myriad ways, and evoke intense, affective reactions, at least for this viewer. This is painting that leaves a lump in your throat.

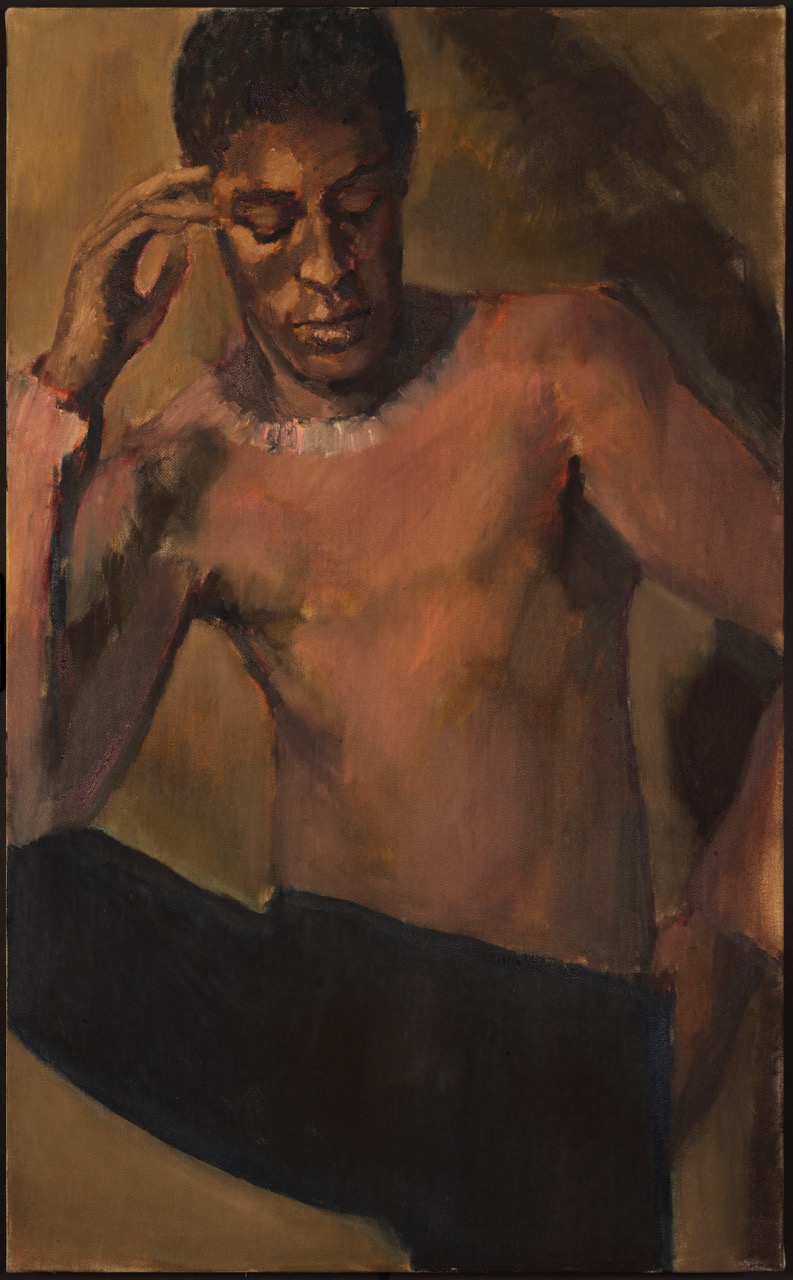

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, An Amber Cluster, 2017. Oil on linen, 51 ⅛ × 31 ½ inches. Image courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, and Jack Shainman Gallery.

Each of them recalls—glancingly, allusively—some of the most iconic images in art history. An Amber Cluster—the image of a man, cropped close, one leg on a chair and arms angled out from his side, his shirt stretched so tight across his torso as to be mistaken, almost, for flesh, save its pink tone and a vague indication of a neckline—channels a Picasso rose-period acrobat; the herringbone-weave canvas on which it is painted hearkens back to Titian. The pair of women in Ever the Women Watchful—one seated in an ornate, wrought-iron chair and the other standing, peering through a looking glass, has a whiff of Édouard Manet, of Gustave Caillebotte, of Mary Cassatt—an impressionist mélange. Vigil for a Horseman, a work made up of three canvases showing a man posed languorously on a couch from three different points of view, has an air of a deconstructed Harlequin, his commedia dell’arte ancestry called forth not in his spandex costume but in the diamond-patterned upholstery and striped drapery that surround him. I could go on. That her subjects are dark-skinned underlines the whiteness of the Western canon, yes, but what could be more natural than a black artist painting bodies that reflect her own? (“They’re all black because . . . I’m not white,” she said in a recent interview.)

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Ever the Women Watchful, 2017. Oil on linen, 78 ¾ × 51 ⅜ inches. Image courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, and Jack Shainman Gallery.

These subtle art historical intimations result in characters who seem oddly familiar despite their anonymity. In this sense, they remind me of Cindy Sherman’s Film Stills, in which the signifiers of classic Hollywood cinema—lighting, composition, costume, pose, hairstyles, makeup, settings—are so cannily deployed that it’s hard to believe there’s no actual film to which the photos correspond. But unlike Sherman’s heroines, which are silver-screen “types,” Yiadom-Boakye’s figures, who all seem to hold themselves, even in repose, with the taut readiness of dancers, have an almost preternatural specificity about them. The touch of fingers to a forehead, the splay of feet, the arch of a back, the furrow of a brow: these are not generic gestures, but ones that bespeak a distinctive being-in-the-body that seems, for lack of a better word, real.

And yet, they are emphatically not real—there is no one, living or dead, that they are meant to reference or call to mind. (The point is made clearly in the wall text that opens the installation.) What should we say instead? “Imaginary” doesn’t quite get at the complexity of their genesis, as they are not invented purely in the mind but rather via magazine cuttings that Yiadom-Boakye gathers in notebooks to use as source materials, grouped in a rough taxonomy of “nudes, different body parts, different sorts of gazes,” per Elena Filipovic, writing in the slim catalogue for the exhibition. Perhaps “fictional” comes closest—not least because the artist has a parallel practice as a writer of short stories, but also because of the pregnancy of each image, the sense that all of these figures hanging on the walls have a biography, an entire life to account for.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Under-Song for a Cipher, installation view. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio. Image courtesy New Museum.

Yiadom-Boakye hangs her canvases low to the ground, so that we can more easily project ourselves into her subjects’ spaces, as bare and undefined as they are. But there are other ways in which our approach—and, as a consequence, our imagined connection with these figures—is impeded. Their faces—the feature that we most associate with a person’s individuality—are, to put it plainly, hard to see. The gallery is quite dark, and the wine-red paint that covers the walls absorbs what light there is. Add to this the fact that the visages are heavily worked in a patchy, impastoed, and scumbled way that lends them a sheen not apparent over the rest of the surface. At first I blamed the lighting, and then my eyes, until I realized—I think—that this effect is wholly deliberate. An encounter with these figures requires work—the viewer must adjust herself, move slightly this way and that, to accommodate them. To grasp them completely, that is to say. Which is what empathy, too, forces us to do: to transform ourselves, in big and small ways, in order to understand other beings in the world—to treat them as fully human, no matter how abstract they might first seem.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and The Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson, and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.