Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In an Indigenous artist’s unsparing work, powerful indictments of

settler-colonial violence.

Nicholas Galanin: It Flows Through, installation view. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery. Pictured, left: Nicholas Galanin, World Clock, 2022. Monotype on paper and accumulating stacks of the New York Times.

Nicholas Galanin: It Flows Through, Peter Blum Gallery,

176 Grand Street, New York City, through July 22, 2022

• • •

The most striking piece in Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist Nicholas Galanin’s show It Flows Through—an exhibition filled with indelible imagery—is White Flag (2022). The sculpture consists of a polar bear rug attached to a wooden pole leaning against the wall. “Attached” is not quite the right word: the hide, a trophy of an early twentieth-century white sport hunter, clings to its wooden mast, grasping it by tooth and claw as its body stretches out, as if whipped by a strong wind. The bear—what is left of it—looks either like it is desperately hanging on for dear life or determinedly seizing its prey. It is at once an image of vulnerability and precarity and of tenacity and strength—an apt description of the condition of both polar bears and Indigenous peoples whose ties to the land are central to their cultures and survival in this era of rapid and devastating climate change. Ecocide is also genocide. But even though the title of the piece refers to a battlefield symbol of surrender, the fierceness of the polar bear’s expression belies quiet capitulation.

Nicholas Galanin, White Flag, 2022. Trimmed polar bear rug and wood. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery.

Galanin’s show includes sculptures, videos, prints, and photographs (most from 2022). Throughout, the work engages the theme of persistence, survival, and power in the face of settler colonialism and its correlates and mechanisms—including capitalism, fossil fuel dependence, suppression of language and ritual, and so many other ills. An eight-foot-tall, totem-like form, Loom is made of stacked, children’s school desks; kid-size chairs broken down to their component parts form two outstretched wings near the top. The reference is unmistakable: starting in the 1830s, settler-colonial governments in North America stole as yet untold numbers of Native children from their homes and placed them in what were benignly called “residential schools” in Canada and “boarding schools” in the US. Their purpose was not so much to educate these children—these hostages, to tell the truth—as to force them to assimilate into the language and culture of their occupiers and to destroy their ties to family and traditions, following the horrible adage “kill the Indian, save the man.” (Lest one mistake this for ancient history, the last of these institutions in Canada was closed in 1997; in the US, as of 2020, at least seven were still in operation.) With the recent discovery of mass graves at Canadian sites, it is clear that thousands of kids died, separated from their parents, who often were never even informed of their loved ones’ fates.

Nicholas Galanin, Loom, 2022. Prefab children’s school desks and chairs with graphite and pencil carving. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery.

Bearing the weight of this history, the visual impact of Loom’s diminutive furniture hits you like a punch in the gut. But look closely at the surfaces and you will see something remarkable, even hopeful and defiant: the desks’ sides and hinged tops are covered with formlines—curvilinear shapes familiar in Northwest Coast Indian art—that trace out simplified animal heads and hands and eyes, like bored doodles of generations of students. The existence of these marks is proof that despite their best, most evil efforts, despite the deplorable loss of life, residential schools failed in their ultimate purpose: there continue to be artists like Galanin, trained in the methods and techniques of their ancestors, who have their cultures flowing through them.

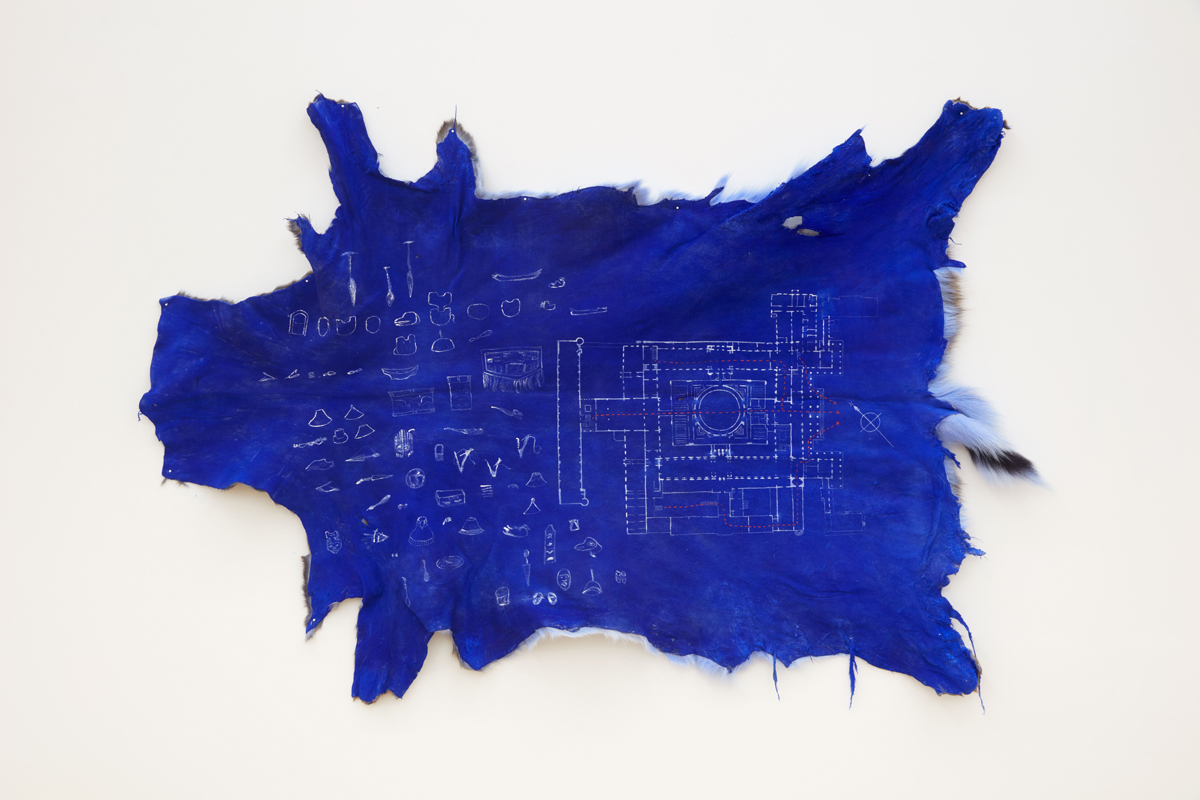

Nicholas Galanin, Architecture of return, escape (The British Museum), 2022. Pigment and acrylic on deer hide. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery.

There is a formal and material virtuosity to Galanin’s practice that underlines its conceptual and historical heft. Take, for instance, Architecture of return, escape (The British Museum) and Purchase, both of which refer to museums’ thievery of Native American cultural productions over centuries. The former consists of a blue-dyed deer hide painted with the floor plan of the British Museum and small, simply drawn representations of the kind of contested objects held in its collection: masks, woven hats, weapons and tools, a blanket. Traditionally, deer-hide paintings were a form of historical communication between generations; what is being transmitted here, it seems, is not only the story of what was stolen, but also something besides. Many Indigenous groups in the Americas consider certain of their cultural objects to be ancestors, living beings. To be held in a museum, away from the life of their people, is a form of incarceration. With orange dotted arrows indicating escape routes, Galanin’s hide is as much a plan for a prison break as anything else. Nearby, Purchase consists of handmade copper lockpicks ensconced in a leather pouch. Each of the tools is incised with a phrase from labels Galanin saw when he visited the Museum of Natural History in New York: “Collected by Emmons from a grave,” “Oldest blanket, handed down,” “Collected” (this last in scare quotes), “From shaman’s grave,” and so on. The picks, in other words, are both records of crimes not often enough seen as such and an invitation to members of the artist’s generation to take the law into their own hands to rectify such past injustices.

Nicholas Galanin, Purchase, 2022. Hand-engraved copper and leather tool bag. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery.

While I might not be the person called to action by Purchase, I am still positioned in relation to the devastating and violent histories and present situations to which it and other works refer as a perpetrator, abettor, passive bystander, or privileged ignoramus. This, to me, is the power of Galanin’s approach—his art makes me squirm. World Clock is composed of a framed monoprint of the front cover of the New York Times bearing an image of Manhattan Island and a blaring, imagined headline—“MANHATTAN RETURNED TO LENAPE”—below which, on the floor, sit piles of the actual paper of record. The piece records an endless wait (the stacked issues mark the passing of time) for an utterly improbable event, and simultaneously manifests such a wish for the land’s return to its original caretakers by speaking it out loud. That speech act seems a pointed rejoinder to the now-familiar land acknowledgements recited at the beginning of every art-world gathering and other liberal lip service to the Land Back movement. World Clock kneecaps such performative gestures by confronting viewers with an actual, concrete form of repair, and forcing them to sit with the question of what such a future might look like.

Aruna D’Souza is currently Edmond J. Safra Visiting Professor at the National Gallery of Art and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She is the editor of the newly released book on Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames & Hudson, 2022). She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.