Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Look at me, I don’t see you: an artist plays with the black female gaze.

Simone Leigh, installation view. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

Simone Leigh, Luhring Augustine, 531 West Twenty-Fourth Street, New York City, through October 20, 2018

• • •

The black woman’s body is, in the racist culture of the US and beyond, a site of many conflicting projections, a vessel of white fears and fantasies. The works that Simone Leigh puts on display in her first solo exhibition at Luhring Augustine—a show that comes on the heels of a year and a half of major awards and accolades and a commission to create a monumental public sculpture for the High Line—do not at all shy away from that fact, not least because they are literal vessels at the same time as being figurative objects.

Simone Leigh, No Face (Bronze), 2018. From an edition of 10 and 2 artist’s proofs. Bronze, 17 ½ × 7 × 6 inches. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

Of the thirteen pieces on view, ten are female busts and bodies, and all but two are ceramic, a material appropriate for their jug- or vase- or container-like forms. No Face (Bronze), placed near the entrance of the first room, is one of the material exceptions. As its title suggests, this smooth ovoid resting on a dark, burnished, columnar neck is made of bronze and has no face. Peer into its hollow head and you will find only a velvety, seductive blackness. A few steps over is No Face (Pannier), the top half of a woman sitting upon a raffia-covered steel armature that functions as the lower half of her body and plinth simultaneously. The woman’s torso, arms akimbo, made from terra-cotta and rubbed to a dull sheen with graphite, is the inverse of No Face (Bronze), in that it replaces the latter’s abstracted, stylized minimalism with a poignant specificity. Cast from a live model, and showing the telltale signs of fingers working clay, the figure communicates both vulnerability and strength—with sagging breasts and wrinkled abdomen and the effects of gravity’s pull around the navel, all arranged in a superhero’s power stance. This resilient body is crowned by a head festooned with small, stylized, porcelain rosebuds in shades of cream, ecru, pale gray, and pale orange. But as with its bronze counterpart, it lacks a face—the chasm of its head contains more blossoms, clinging to the interior like the most enchanting barnacles, or like the crystalline shards that reveal themselves upon cracking open a geode.

Simone Leigh, No Face (Pannier), 2018. Terracotta, graphite, salt-fired porcelain, steel, raffia, 72 ⅝ × 75 × 58 inches. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

Among the sculptures here (all from 2018) are a number of glazed, salt-fired stoneware “face jugs,” objects that trace their lineage to early African American pottery traditions, and even further back to West African and Greek and Roman classical sculpture. In an interview from 2015, Leigh said that the face jugs of the black diaspora were “made to look ugly to ward off evil spirits,” but if there is ugliness in her versions of the form it is of the most jolie laide variety. Head with Cobalt comprises a head set on a thick neck, with a footed base, a curved handle emerging from the back of its skull, and a flared opening at the top—the latter element turns this object into a vessel, while at the same time functioning as a crown. Its features—the two that it has—are unmistakably African: wide, flat nose and full lips, marks of beauty for some and derision for others. There are no eyes for this face to see, no ears to hear. The pot is glazed black, for the most part, but examine the flared opening and you will notice that the edge and the interior are dappled in milky white and cobalt blue (the result of Leigh’s labor-intensive salt-firing technique); that same white and cobalt is finely spattered over the side of the head and along the edge of the lips. The effect is cosmic—a metaphor, perhaps, for the realms of knowledge and imagination, as plentiful as the stars, that black women have carried with them over generations and across oceans in order to persist and survive, to maintain cultural traditions and ensure community.

Simone Leigh, Head with Cobalt, 2018. Salt-fired porcelain, 15 × 7 × 11 ¾ inches. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

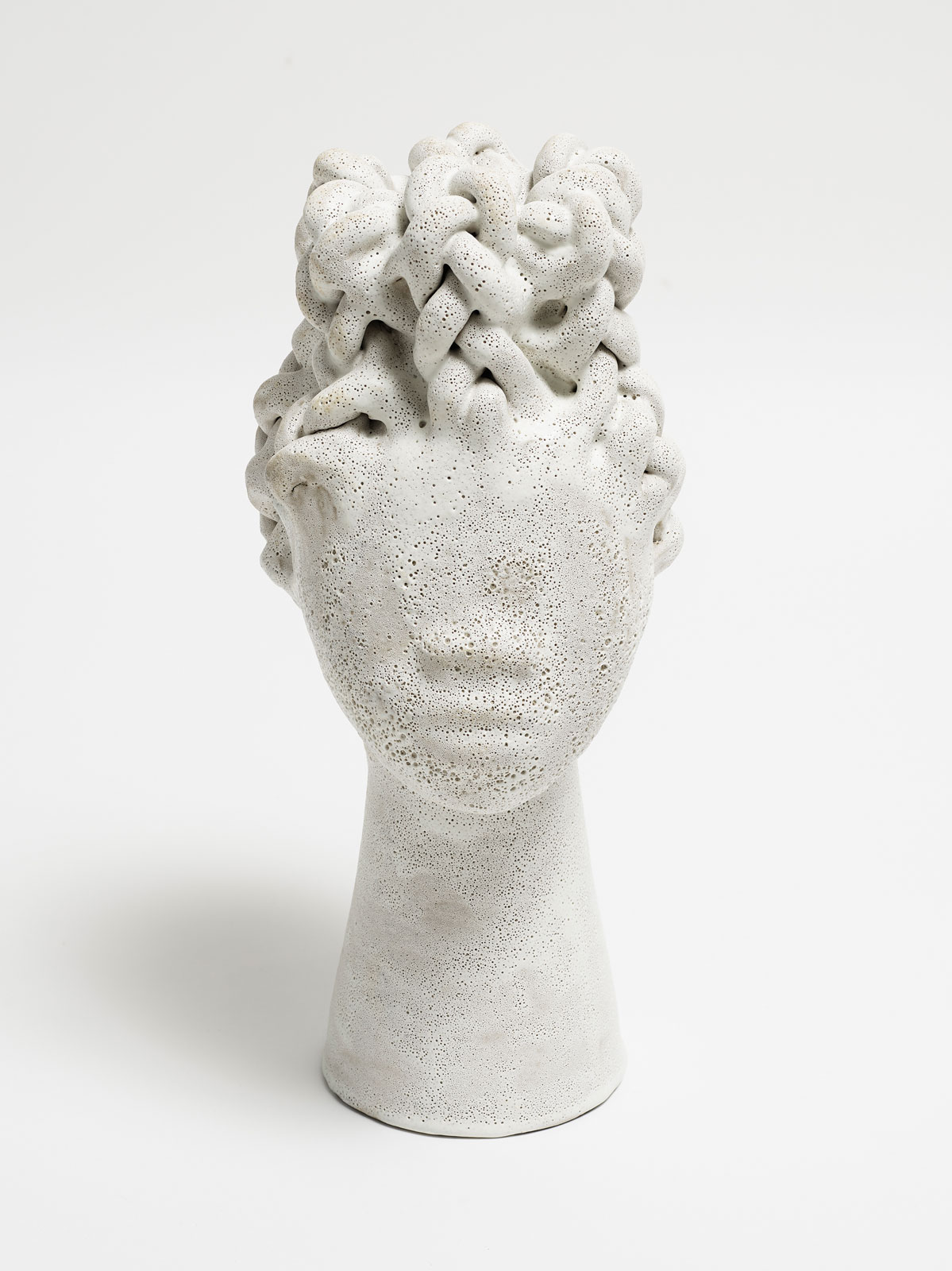

The Village Series #4 is a smallish bust, not quite eighteen inches high, sitting on a wood-veneered cylindrical column in the back room of the show: head on columnar neck, with the same mouth and nose as Head with Cobalt but now softened. It is the work that has haunted me most in the days since my visit. As with many of the salt-fired pieces here, the glazing is the real story: the slightly matte, creamy white surface is covered with holes, ranging from tiny pinpricks to smallish perforations, in an irregular pattern. Reading at once as freckles, pockmarks, and the Milky Way, the pitting is repulsive and gorgeous, the very definition of sublimity.

Simone Leigh, The Village Series #4, 2018. Stoneware, 17 ¾ × 8 ¼ × 10 inches. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

A crown of ropy braids tops this head. This braiding appears in four nonrepresentational works sitting directly on the floor in the front room, too—bell-shaped cloches seamed with plaits, ranging from sixteen to twenty-five inches high, also part of The Village Series. The slippage between bodies and architecture alluded to in the title of a series comprising both figurative and abstract forms—is a village a collection of people or an accumulation of dwellings?—is reiterated throughout the show, most strikingly in the ten-and-a-half-foot-tall Cupboard VIII, which adopts the raffia-over-steel structure familiar in Leigh’s oeuvre. The work’s appearance and title point to, among a number of things, an actual restaurant in Natchez, Mississippi, built in the shape of a giant, grotesque mammy; you enter it by penetrating her sculpted skirt. Leigh removes the entrance; her version of this edifice is impenetrable. Here, it is surmounted with a stoneware torso whose head takes the form of a tipped-over water jug, and whose hands are glazed to a glossy shine as they make a gesture of offering.

Simone Leigh, Cupboard VIII, 2018. Stoneware, steel, raffia, Albany slip, 125 × 120 inches. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

Although vessels, the figures who populate Leigh’s show cannot be filled with the imaginings of whiteness, because they are already replete: faceless or eyeless, in declining to return the viewer’s gaze they resist being cast in others’ terms. The result is a singular beauty, one that is nakedly and poignantly exposed, but that insists at the same time on maintaining its own boundaries, guarding its right not to speak or answer, existing independent of others’ expectations or requirements.

Simone Leigh, installation view. © Simone Leigh. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

The artist has said more than once that her work is for black women—a statement that I read as a commitment to holding space for people who have been marginalized in myriad ways by the art world. But at the same time she operates quite fully in that art world, especially now, when she is being celebrated after a career spent working away from the limelight, having achieved the extraordinary feat of inserting ceramics—still mostly understood as a “craft”—quite seamlessly into the realm of contemporary sculpture. Leigh, an artist who is at the height of her powers and in full control of her medium, is creating work about and for black women that is, at the same time, more than enough to satisfy the rest of us, even as it withholds its secrets; her sculptures embody an act of refusal that is at once defiant and generous. They will not see us, and will not allow us to see them in their completeness, these anonymous, sightless beings, but they still allow us to experience their intense, visceral beauty. A fair trade, it seems to me.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.