Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

The work of art in the age of computerized production,

now on view at LACMA.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, installation view. Photo: Museum Associates / LACMA. Pictured, center foreground: Edward Kienholz, The Friendly Grey Computer—Star Gauge Model #54, 1965.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, curated by Leslie Jones, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Boulevard,

Los Angeles, through July 2, 2023

• • •

The first thing one notices upon stepping into Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age—a survey of art and technology from the 1950s to the early 1980s, now on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)—is what looks to be a cheerful robot, sitting squarely in the center of the room.

Technically, it’s not a robot, though it feels like it could be a character from The Jetsons or a charmingly old sci-fi film. It is Edward Kienholz’s The Friendly Grey Computer—Star Gauge Model #54 (1965), a heavy, boxy metallic construction perched on a comfy rocking chair, which gives the hulking piece a homespun touch. There are knobs, dials, and lights up top, suggesting two large electronic eyes on a chunky body. There is a telephone built into it, and a ream of index cards. Upon closer inspection, one discerns the slightly demented addition of tiny doll legs jutting out of the front.

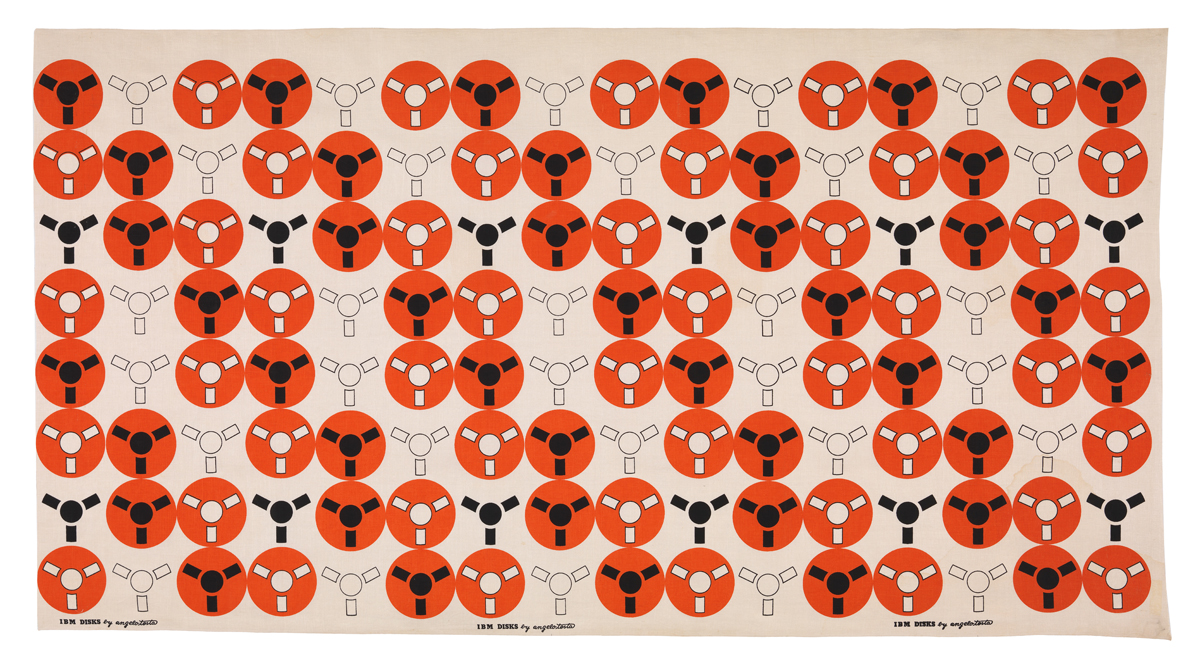

Angelo Testa, IBM Disks, 1952–56. Linen plain weave, screenprinted, 104 3/4 × 51 3/4 inches. Photo: Museum Associates / LACMA.

The sculpture is situated in a gallery devoted to the computer’s place in popular culture. None of the works in this room—which include fabric designer Angelo Testa’s linen piece IBM Disks (1952–56) and Lowell Nesbitt’s hauntingly photorealistic painting I.B.M. Disc Pack (1965)—actually involved computing in their making. That’s the purview of the other five galleries in the exhibition, which delve into art’s relationship to mathematics, computer programs created to produce (and reproduce) artworks, algorithmic approaches (with and without computers) to artmaking, data and information as artistic media, artists who expressed their politics through technologies, and “open scores” designed to allow for many idiosyncratic performances of a single work.

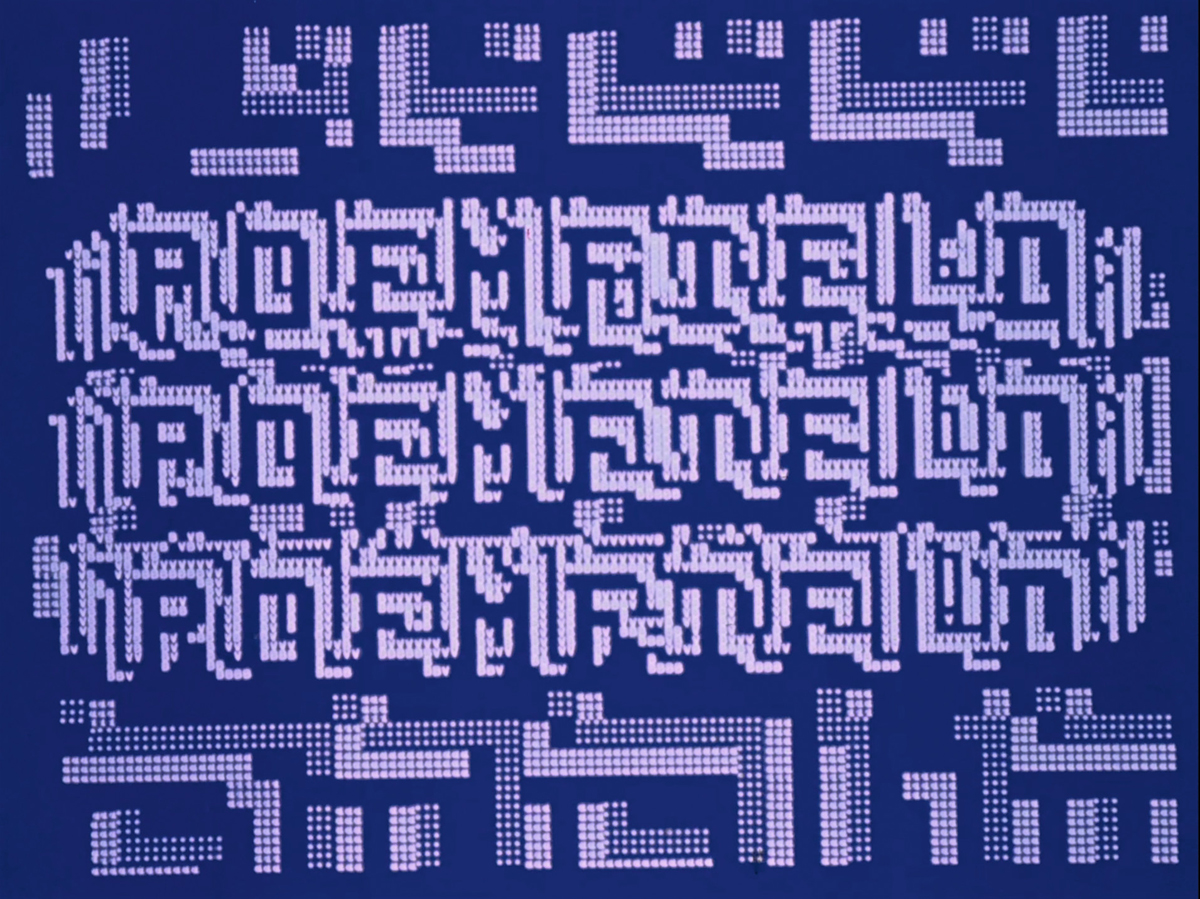

Stan VanDerBeek and Kenneth C. Knowlton, Poemfield No. 1 (Blue Version), 1967 (still). 16mm film transferred to video, 4 minutes 41 seconds. Courtesy The Box. © Estate of Stan VanDerBeek.

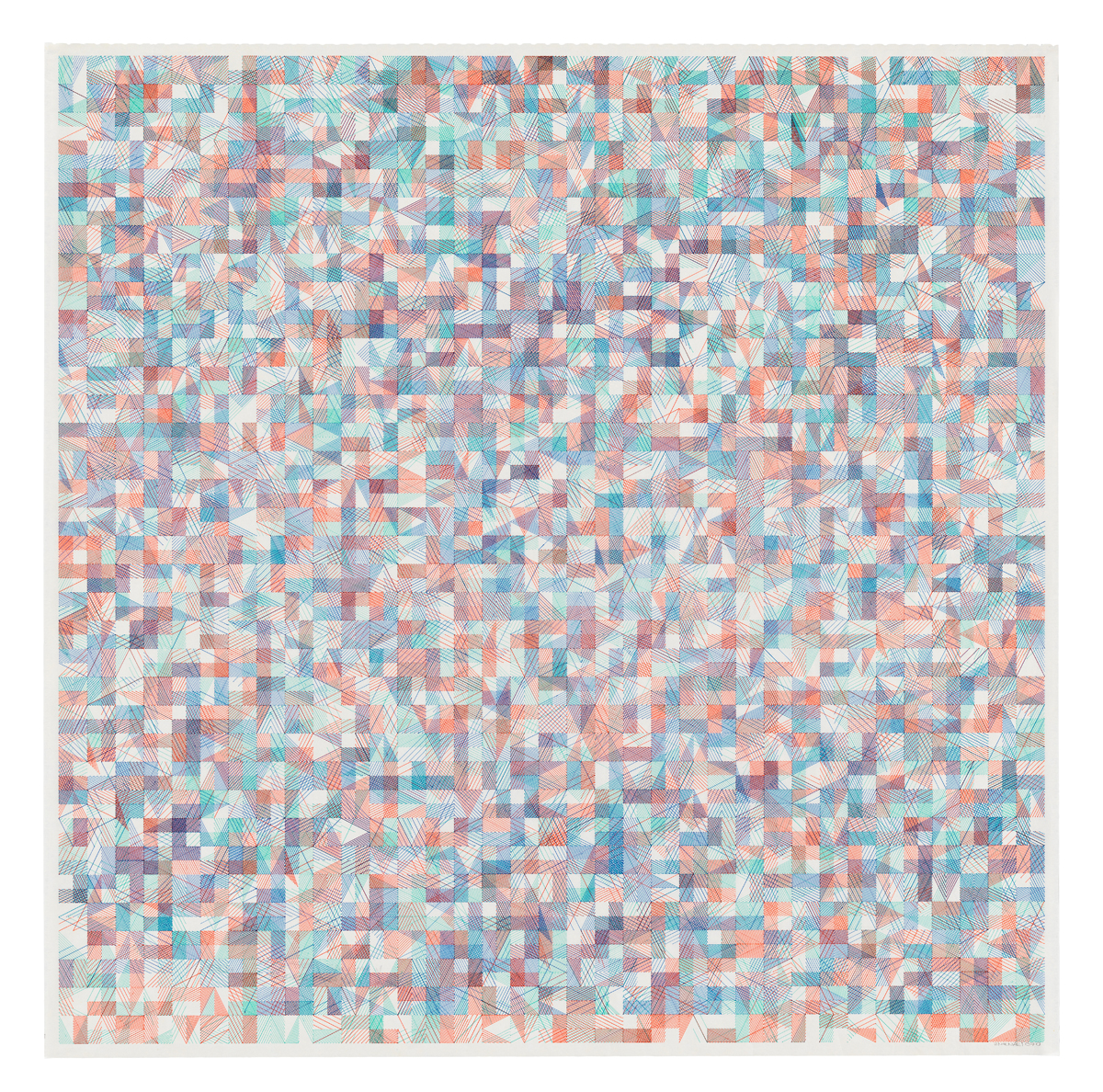

The usual suspects of early computer-art histories are to be found within: A. Michael Noll, Kenneth Knowlton, Lillian Schwartz, Stan VanDerBeek, and Manfred Mohr, to name just a few. The exhibition resembles a compilation, in a way, of the “greatest hits” of twentieth-century technology-based art, featuring pieces like Alison Knowles’s pioneering computerized poem The House of Dust (1967); VanDerBeek’s exuberant film Poemfield No. 1 (Blue Version) (1967), generated via Knowlton’s own custom coding language; and Vera Molnár’s delicate plotter drawing À la recherche de Paul Klee (1970).

Vera Molnár, À la recherche de Paul Klee, 1970. Ink plotter drawing, 29 1/8 × 29 1/8 inches. Photo: Museum Associates / LACMA. © Vera Molnár.

And yet, something vital to Coded’s history of art and technology is missing: computer music, which has only the faintest of presences here. There is an essay near the end of the exhibition catalog, along with a good playlist curated by Mark “Frosty” McNeill, but it feels like an addendum and not part of the main course. One wishes that Coded would have dared to play John Cage and Lejaren Hiller’s chaotic computer-music extravaganza HPSCHD (1969) out loud inside the exhibition instead of just showing a poster from the event, or at least given us a sense of HPSCHD’s overpowering visual experience, which involved thousands of slides. One can hear bits of audio if touring the exhibition with headphones, but few viewers appeared to be doing so when I was there, and music is not placed in a way that feels clear and connected. It would also have been nice to see representation in the galleries of Max Mathews, the father of computer music, who was connected to several of the artists here during his tenure at Bell Labs.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, installation view. Photo: Museum Associates / LACMA.

Perhaps even more problematic, though, the narrative that Coded builds can be disappointingly conventional, placing artists who were trying to develop new modes of expression using the emerging technologies of their time alongside more accepted standbys of twentieth-century art history, like Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt. “I wanted to recontextualize the material, not to remarginalize it, by looking at it again ‘in its moment’ and in relation to contemporaneous art movements such as Op and conceptual art, for example,” LACMA curator Leslie Jones explained in a Studio International interview. In a recent review of Coded published in Outland, art-and-computing scholar Lindsay Caplan judges this recontextualization harshly: “The exhibition is explicitly a recuperative project aimed at situating early computer art within mainstream art history—the terms of which, Coded presumes, are static and set.” She deems the show’s myriad comparisons “the most unimaginative art-historical terrain possible.”

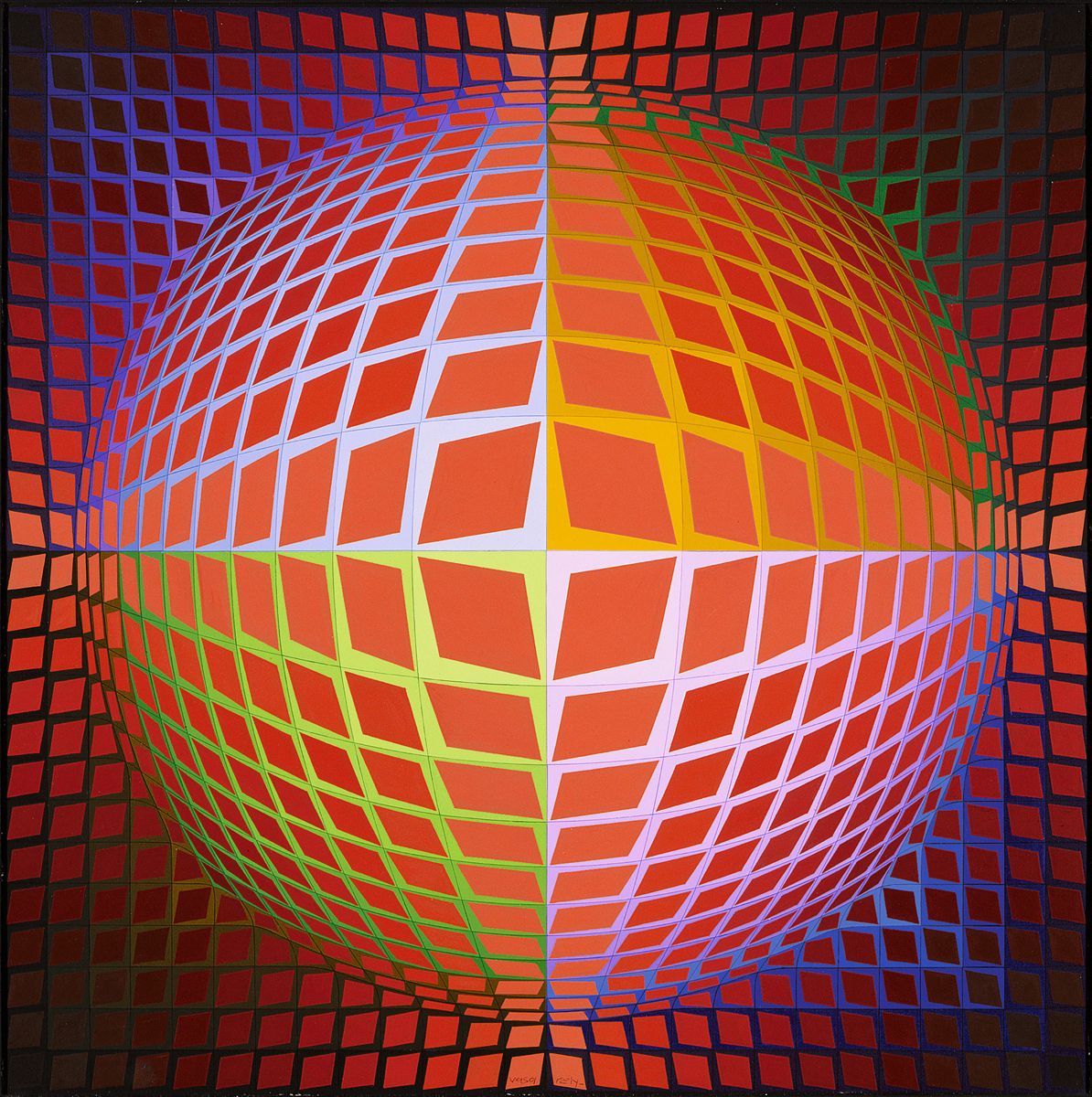

Victor Vasarely, Vega-Kontosh-Va, 1971. Tempera on panel, 25 11/16 × 25 11/16 inches. Photo: Museum Associates / LACMA. © Artists Rights Society / ADAGP.

Caplan’s scathing essay brings up many sharp and trenchant criticisms. My overall take is more charitable; despite its limitations, I largely see Coded as a fun exhibition, but occasionally too dense with curatorial and art historical references. For a viewer with a vested interest and background in the subject (I, for one, am nerdy enough to have marinated myself in vintage catalogs for computer-art exhibitions), tracing those citations can be enjoyable, to an extent, like playing a trivia game. For instance, I saw in Victor Vasarely’s luminous, pulsating, illusorily three-dimensional painting Vega-Kontosh-Va (1971) a nod to LACMA’s vaunted Art and Technology program, which ended in 1971 and counted Vasarely among its participants (though Vasarely’s fantastical and ambitious proposal was not realized). Kienholz’s quirky sculpture was displayed at MoMA’s The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age in 1968, and there are references to the watershed Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition curated by Jasia Reichardt at the ICA in London that same year. (Jones had originally planned for Coded to debut in 2018, to align with the fiftieth anniversary of Cybernetic Serendipity.)

Some of the references are baked into the works themselves—for instance, Noll’s computer-created undulating shapes (Ninety Parallel Sinusoids, 1964) were originally inspired by the soft, mesmerizing waves of Bridget Riley’s Currents; but showing works by the two artists side by side here feels too literal, leaving little to the imagination. Ultimately, the exhibition’s many “coded” references—forgive the pun—fail to build an exhibition that could resonate powerfully with a general audience.

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, installation view. Photo: Museum Associates / LACMA. Pictured, center foreground: Hans Haacke, News, 1969/2008. Center of back right wall: Calvin Sumsion and Gary Viskupic, poster for HPSCHD, 1969. Screenprint.

But part of the problem may have to do with the fact that art made with emerging technologies risks appearing obsolete to new audiences. Take Hans Haacke’s News (1969/2008), a herald from the historic 1970 Software exhibition at the Jewish Museum. Set up in a popular corner of Coded, Haacke’s teletype machine busily spews a seemingly never-ending readout of the latest news that urgently grows longer and longer. Created at the height of the Vietnam War, the work was a fiery political statement in its moment, and, in its real-time materialization of newswire feeds, technologically revolutionary. Here at LACMA, in 2023, a group of mostly young onlookers drawn to the piece seemed confused, even a bit nonplussed. “So it’s like . . . Twitter?” one said. “What a waste of paper,” said another, as the machine continued its loud churn of frenetic printouts. “Are they going to recycle that?”

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.