Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

The sound trek: Paris to Calcutta documents a twelve thousand–mile pursuit of folk music.

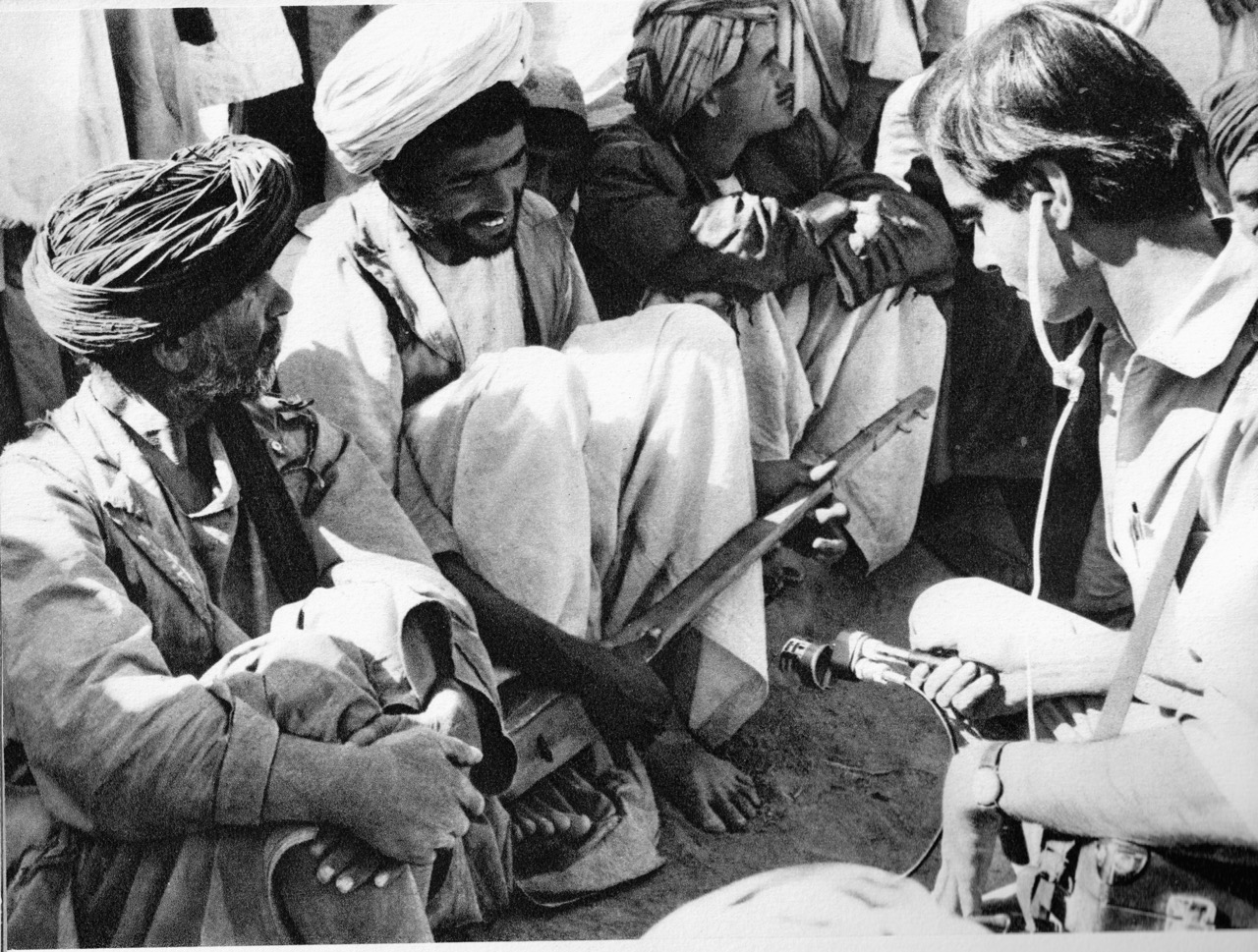

Deben Bhattacharya recording in Afghanistan, 1955. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road.

Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, by Deben Bhattacharya, Sublime Frequencies, 160 pages, $48

• • •

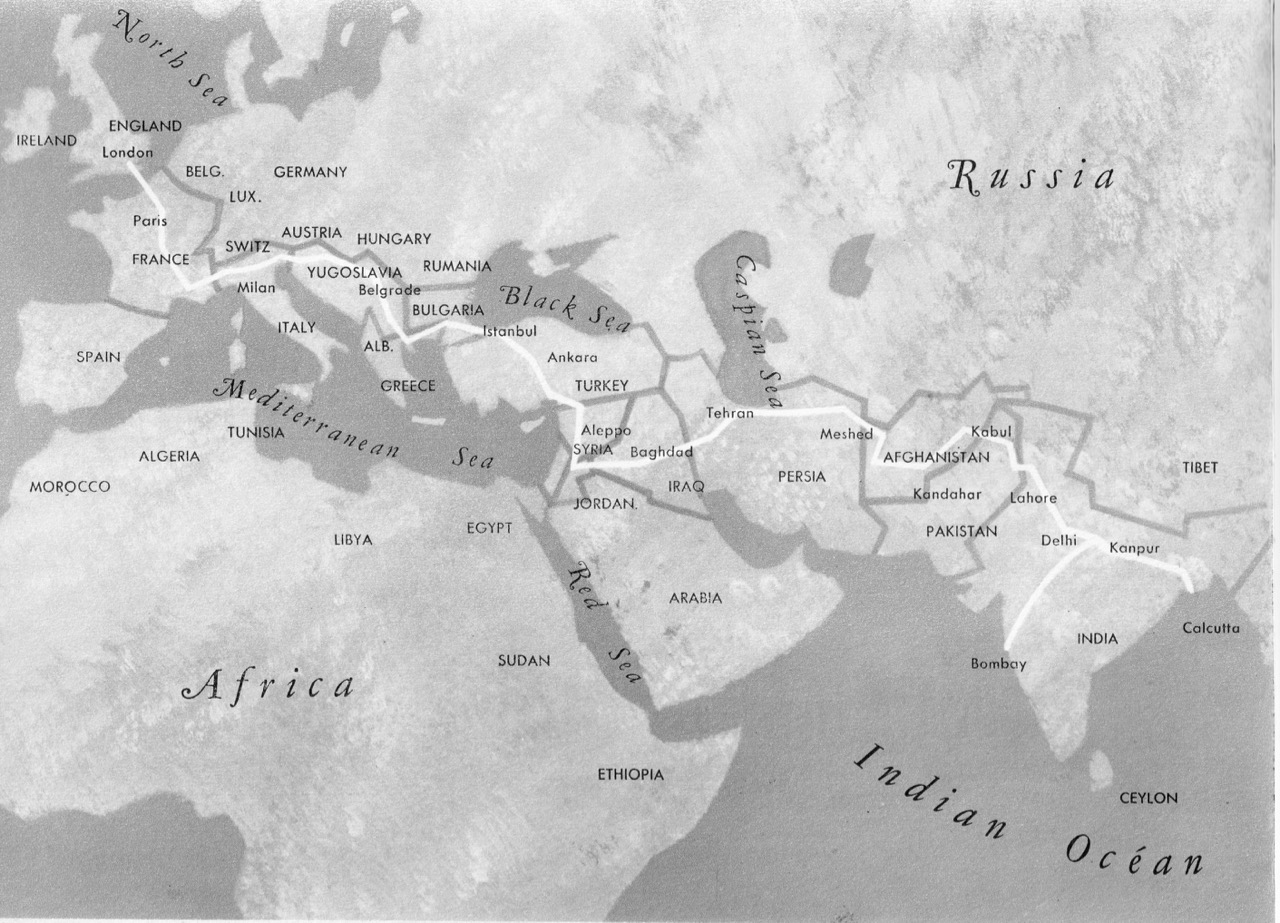

In 1955, a radio producer named Deben Bhattacharya traveled from France to India in a converted milk van with the goal of making field recordings. His friend Colin Glennie did the driving for the epic twelve thousand–mile road trip, motivated by the possibility of meeting the master architect Le Corbusier, who was then in Chandigarh. The best-known distillation of the recordings from this ambitious trek was an album called Music on the Desert Road.

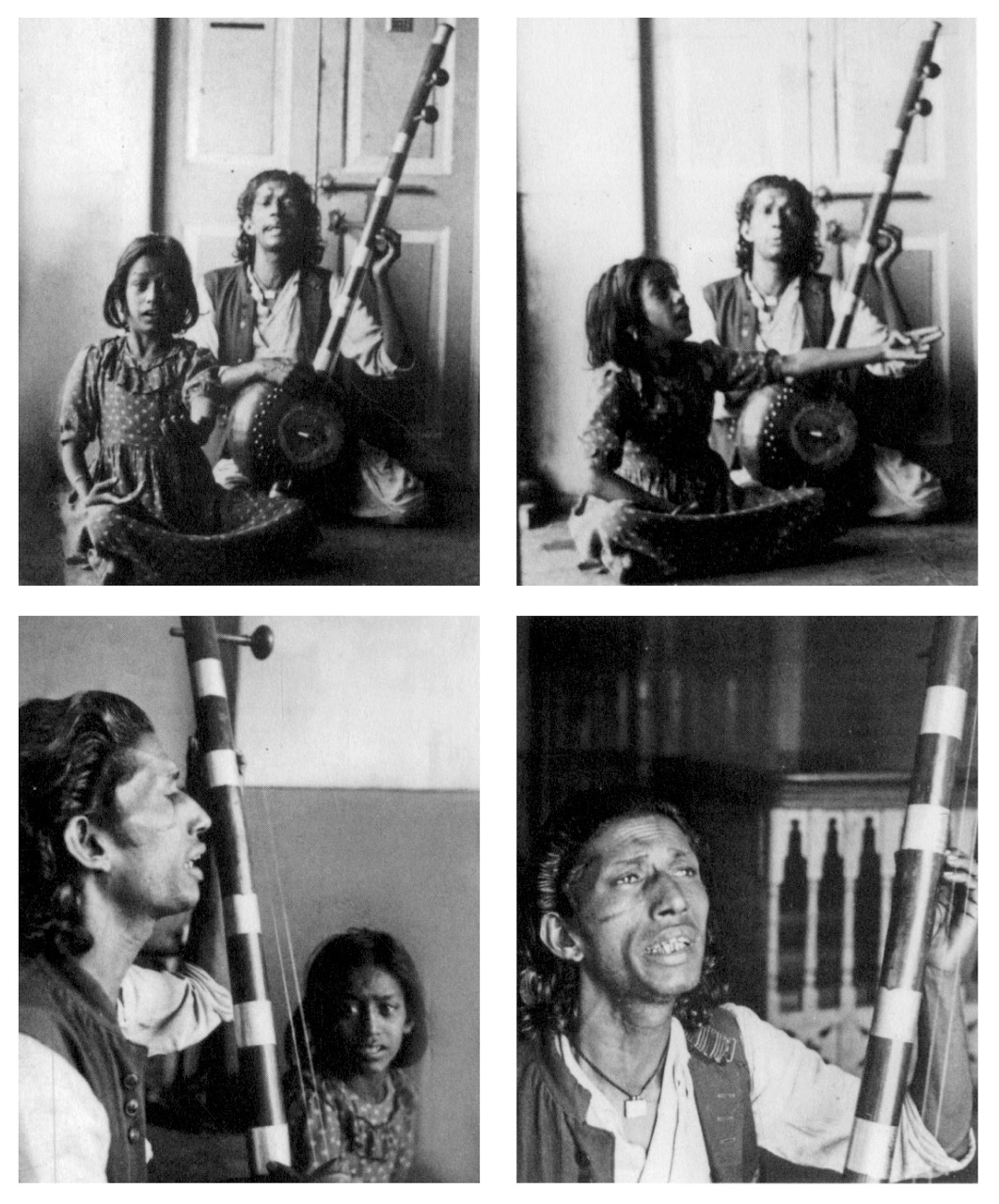

Jai Chand Bhagat and Babu, street singers, Bombay (Mumbai), India. Photo: Deben Bhattacharya. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, page 105.

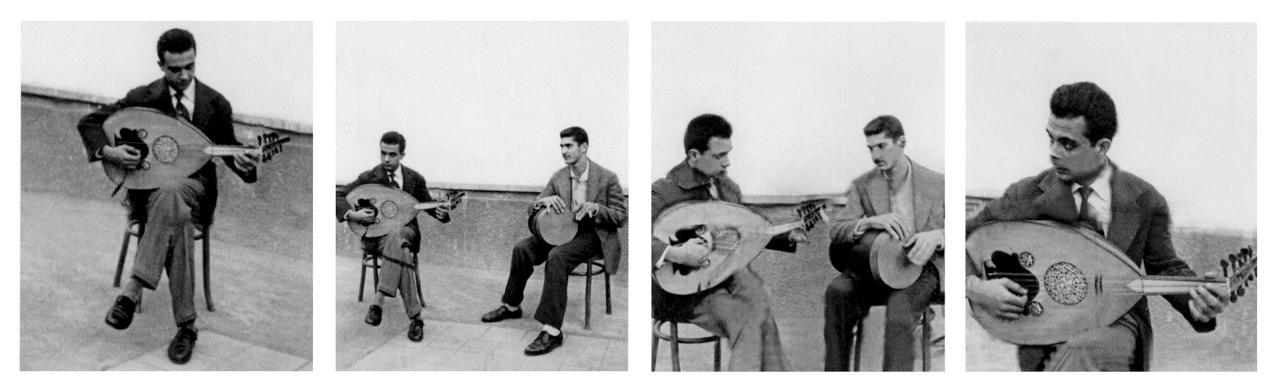

The Sublime Frequencies label has now published Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, a lavish hardcover tome documenting Bhattacharya’s journey, produced and edited by Robert Millis (author of Indian Talking Machine, a book that documented vintage record collections on the subcontinent). Paris to Calcutta includes four CDs of field recordings, along with Bhattacharya’s detailed diary of his travels and numerous scans of his elaborate typewritten notes. Dozens of his striking black-and-white photographs fill out the volume—including images of a Bedouin camp, musicians in Tehran, and street singers in Bombay.

Unidentified oud and zarb players, Tehran, Iran. Photo: Deben Bhattacharya. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, page 89.

Many famous “world music” recordings have been assembled by Western sources over the years, and released on powerhouse labels like Smithsonian Folkways in the United States and the Ocora label in France. We tend to forget figures like Bhattacharya, who was from India—he was born there in 1921 and raised in the mystical holy city of Benares, now better known as Varanasi. He moved to London in his twenties, and later to Stockholm, and did major work for the BBC, UNESCO, and several record labels, producing a huge number of albums, documentary films, and radio shows. Bhattacharya died in 2001, and should be better known for his sizable contributions in the areas of field recording and folk music.

Deben Bhattacharya, desert road trip map, 1955. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road.

During his 1955 overland adventure to India, Bhattacharya crossed through Italy, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. (He and Glennie were joined by a third explorer, who dropped out of the trip partway through.) As Italy faded into the distance, the thrill began to mount. “Suddenly for the first time since I had started this journey, I felt a strange excitement,” Bhattacharya wrote in his diary. “I felt it affect the others too. Like a bunch of schoolboys we started clapping and singing as the van tore along the autostrada, making for Trieste. . . . After midday we were across the border into Yugoslavia.”

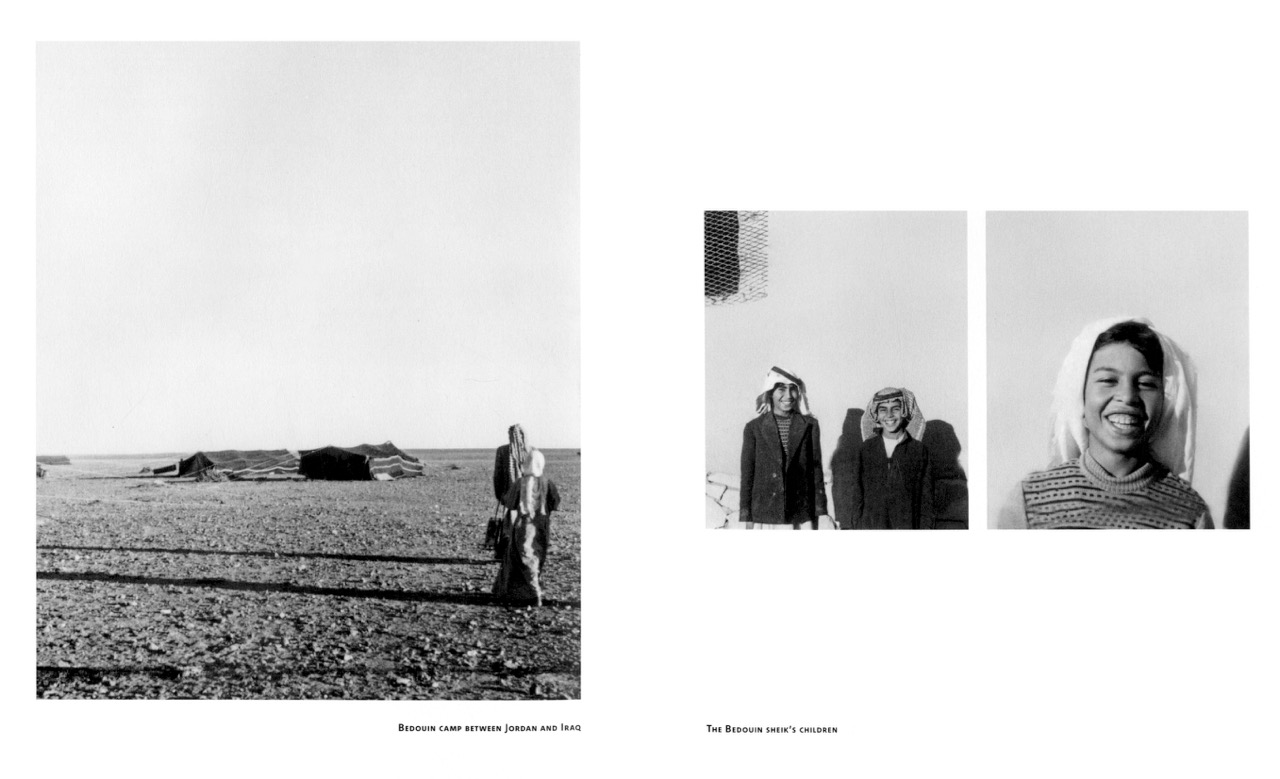

Bhattacharya began recording after he reached the Bosphorus, documenting as much music as he possibly could with a microphone and a clunky reel-to-reel tape machine powered by a car battery. “The most exciting aspect of the journey,” he wrote, “was the constant unpredictability of our human encounters. One evening we should be with the Bedouins in the middle of the Arabian desert, and the next, perhaps at a petrol pump or at a wayside rest house where pilgrims and peasants hum through the nights.”

Bedouin camp between Jordan and Iraq (left) and the Bedouin sheikh’s children (right). Photo: Deben Bhattacharya. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, pages 80–81.

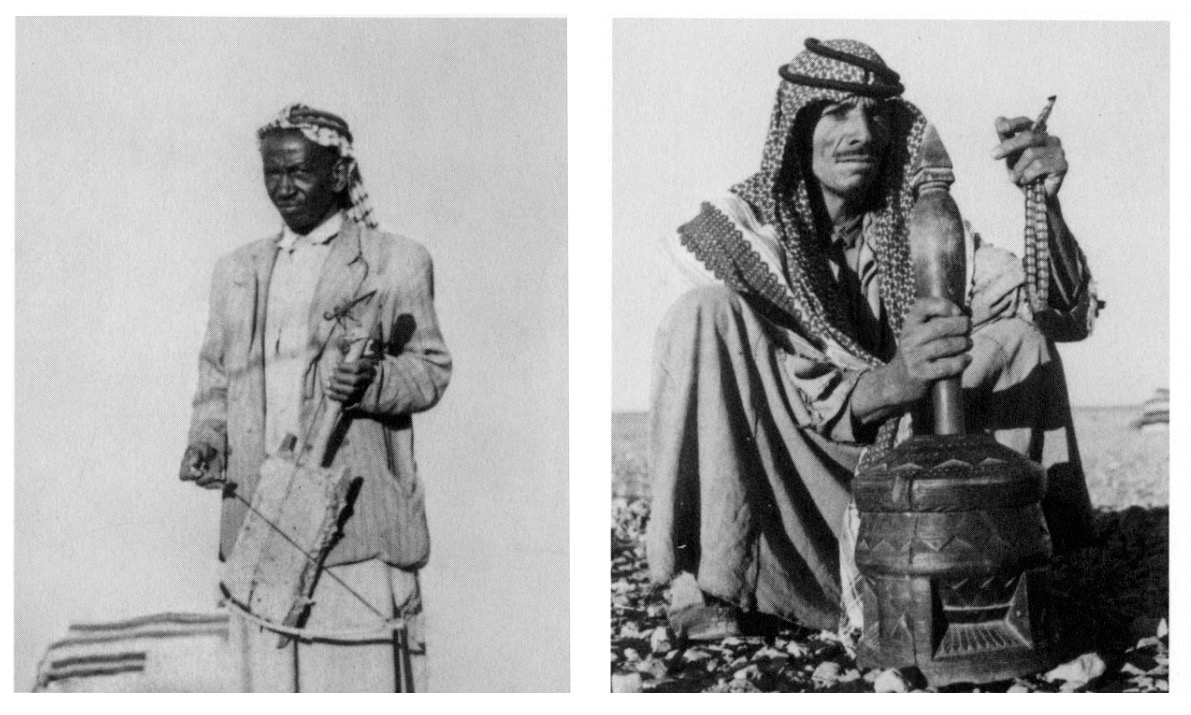

Bhattacharya’s language is richly evocative, conjuring images of glittering sands, labyrinthine cities, and winding dirt roads darkening in the desert dusk. His writing is also deeply musical—not just in the easy rhythm of his words, but in his sonic descriptions: piles of pistachios crackling in peoples’ hands in Iraq; the metallic rattling of the van on bumpy roads in Afghanistan; the croaking of frogs in the Barakar river on the edge of Bengal. He wrote about Bedouin singers outside of Amman pounding coffee beans with a mortar and pestle, and his description is so vivid that you can practically smell the air. (Bhattacharya also made an intriguing recording, included on the second CD, of two Bedouin coffee grinders working rhythmically, generating a catchy pitter-patter).

Hazim with rebab, Bedouin camp (left), and unidentified Bedouin coffee grinder with mortar and pestle (right). Photo: Deben Bhattacharya. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, page 85.

Bhattacharya mainly focused on what he considered to be the traditional folk music of the countries he visited—music he felt was untainted by the shifting trends of the West. In Turkey, he lamented: “They were all eager to show off their knowledge of Western music—the stock names of Mozart, Beethoven and Wagner—and then, of course, there was Turkish Cabaret and Jazz too! I was feeling tired and depressed . . . there was this lack of love and pride for what was their own.”

Bhattacharya seemed to have little interest in radio broadcasts or popular music, which is too bad, because it would have created a fuller picture. “I wish he had recorded the ‘noisy’ ‘blaring’ radios that ‘did not attract’ him at all: what a glimpse into that time we could have had,” writes Millis in the introduction. It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of the recordings he culled from the Middle East were of male musicians; he wrote that women were often hidden from view (the subtitle Men and Music on the Desert Road is apt).

In Damascus, Bhattacharya had a major musical revelation. “For the first time since we started touring through the Arab countries, I felt a thrill rising through my spine as I placed my microphone near the mouth of the leader of the dervish singers,” he wrote. “Here, at last, was music with life in it, music such as I had come across in India, or in the gypsy festival of Les Saintes Maries de la Mer in the South of France, or in Andalusia. It was music which was not isolated from life and religion.”

Bhattacharya’s vibrant depictions of Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan in the 1950s, countries that have been so torn by war and destruction in recent years, are a poignant read. Cities like Aleppo, Baghdad, and Kabul are mostly familiar to Westerners today from catastrophic events in the news; his exploration of these places gives a sense of their bygone grandeur. Bhattacharya recorded violin improvisations in Syria, Kurdish ballads in Iraq, and dance songs in Afghanistan (these and many other tracks are included in the book’s CDs).

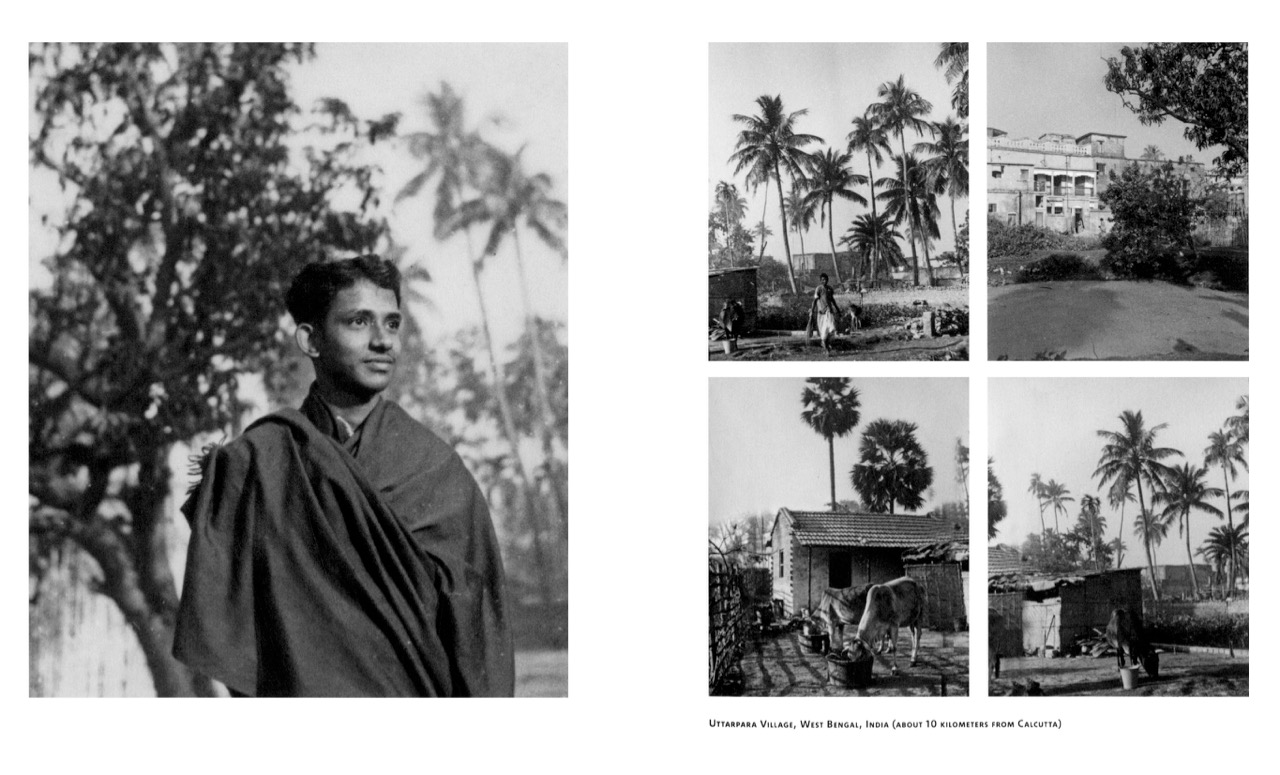

Uttarpara Village, West Bengal, India (about 10 kilometers from Calcutta). Photo: Deben Bhattacharya. From Paris to Calcutta: Men and Music on the Desert Road, pages 102–03.

Some of Bhattacharya’s best writing comes toward the end of his manuscript, as he moves into more familiar terrain—Pakistan and then India. “A dry cool breeze; and the early winter sun crisply simmers over the city of Peshawar,” he wrote. “The betel leaf and cigarette stalls, the sweet vendor, the news hawker and the tea shops with blaring radios glow in the brittle light.” When they crossed into India and reached Chandigarh, Glennie was elated to finally experience Le Corbusier’s modernist city, in the presence of the architect himself (Bhattacharya was less thrilled, writing that “all the steel and concrete of Chandigarh seemed only a costly failure.”)

Bhattacharya and Glennie made a pit stop in Benares, and Bhattacharya seemed inspired by his return to his ancient hometown. In his diary, he wrote an extended meditation on Indian classical music and the structure and lore of the raga, and his flowery phrases creatively mirror the music. But as Bhattacharya was quick to note, he didn’t think of himself as a musician. His instrument, as he once explained, was the tape recorder.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.