Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Bloody pig heads, jagged music: an exhibition revisits the performance artist’s work.

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Johanna Went: Passion Container, the Box, 805 Traction Avenue,

Los Angeles, through March 14, 2020

• • •

The radical performance artist Johanna Went is one of the true legends of the California underground, and one who deserves much wider renown. I first came across her name about two decades ago, while interviewing some punk and post-punk bands from the 1980s. Musicians would talk in awed tones about Went’s infamous shows at venues like San Francisco’s now-defunct Mabuhay Gardens and the late Hong Kong Café in Los Angeles. She was known for transfixing and sometimes gory performances, featuring fantastical costumes made of materials filched from dumpsters and strange, ritualistic improvised music. But detailed information about her work was disappointingly hard to find. When Lady Gaga debuted her meat dress in 2010, I had a flashback: it sounded like something Went would have done in 1982. In a just world, Johanna Went would be as much of a household name as Lady Gaga.

One of the best sources of information on Went is RE/Search #6/7: Industrial Culture Handbook, a 1983 bible for the industrial music landscape edited by V. Vale and Andrea Juno. The book includes interviews with well-known bands like Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire, but also with key figures in the subculture who formed the vital connective tissue of entire scenes. These were people like Mark Pauline, the wily founder of robot wrecking crew Survival Research Laboratories, and musician and provocateur Monte Cazazza, who originally coined the term “industrial music.”

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Most potently, the book includes a no-holds-barred interview with Went, who comes across as the most wildly unnerving and fascinating of them all. In her interview, she nonchalantly chats about doing a live performance with a dead cat, wandering graveyards on hot nights, and wearing a “wedding dress with bloody kotexes on it.” She talks avidly about using pigs’ heads, plastic doll parts, fake blood, and real blood, recollecting with relish a performance where she transformed into a Statue of Liberty that projectile-vomited gore onto the audience (with the help of a pump rigged by Pauline). “I cannot believe that people are disgusted by certain things,” she says in the interview. “I just can’t! Sometimes it just amazes me—the things that people are upset by. . . . I don’t understand why people don’t laugh more. I almost laugh during the whole show. And most of the things that I use in the show I think are funny.”

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

The Los Angeles gallery the Box has mounted a necessary and wide-ranging retrospective of Went’s work from the 1970s to the 2000s titled Passion Container, its name derived from a 1988 performance. Numerous soft sculptures and costumes fill the space—colorful, hilarious, and often grotesque characters, arranged dynamically as if they were attending a particularly demented party. As you look at them leering and posing, they seem almost alive. Many of these outfits were originally worn by Went in her early stage performances.

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Pictured: Shark Head.

In Shark Head (1983), a head festooned with plastic sharks is perched atop a plastic poodle sprouting out of a chest, with the front of a Tide detergent box inexplicably affixed below it, to what appears to be a kimono. More recent works, like Crone (2007)—which looks like a fully formed alien being with scraggly hair, ready to pounce at any moment—show more refined craftsmanship. The simplicity and scrappiness of earlier pieces, though, is genius, like Big Head (1988), a giant, lopsided visage complete with a third eye, a bulbous nose, and disturbingly pillowy lips.

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio. Pictured, foreground: The Traveling Suit.

Some of these pieces have long histories—started decades earlier, and augmented later. In Untitled (1986/2007), a two-headed nun sports a more recent addition: a meticulously arranged wreath of hundreds of smiling doll heads, encircling the original figure like a nightmare straight out of the movie Child’s Play. In The Traveling Suit (1982/2007), a plaster cast of Went’s youthful face from 1982 is conjoined with an older body, created much later, with a grandmotherly crocheted hat, skeins of yarn, and a heavy coat. A few of the characters seem like they could be friends with apparitions constructed by the late artist and erstwhile rapper Rammellzee, who labored at the same time on the opposite coast.

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

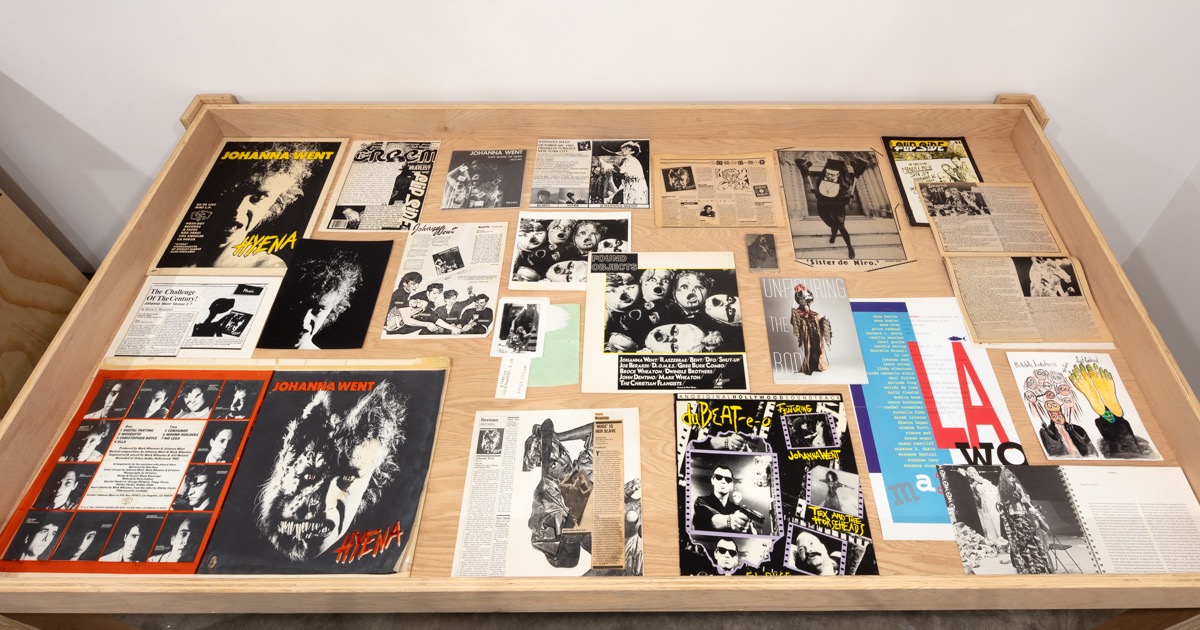

Passion Container also has several vitrines filled with documentation of Went’s performances—they display a panoply of Xeroxed and collaged punk show flyers, and rare interviews and features on Went from extinct zines like No Mag, SLASH, Velvet, and Ego (most of them sadly unreadable, being encased under glass). Videos of early performances are projected onto the bare white walls of the gallery, giving a sense of how energetic and visceral these shows were.

Johanna Went: Passion Container, installation view. Image courtesy the artist and the Box. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Went also made a lot of jagged, intense music, created both in partnership with her longtime collaborator Mark Wheaton, who began working with her in 1979, and many other musicians. Her 1982 EP Hyena has just received the deluxe-reissue treatment from Box Editions—a handsome album on “blood-red vinyl,” the stark black cover depicting half of Went’s face, and half of the animal’s. Hyena is an invigorating listen, but the thrill is partly lost in the translation to the recorded medium. Without the context of a live gig, it feels less pointed and immediate.

Passion Container is a crucial step in reviving Went’s riveting body of work. Further exhibitions globally would help to reassert her legacy as one of the most distinctive performance artists of our time—not just on the West Coast, but the world at large. But there should be more—perhaps a book, a tour, a major documentary. And this work shouldn’t just live in the visual-art world; it should be part of the history of music. The stories of punk, post-punk, and industrial music would not have been the same without her searing and original presence.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.