Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

In a new album, the legendary composers capture their half-century-long love story.

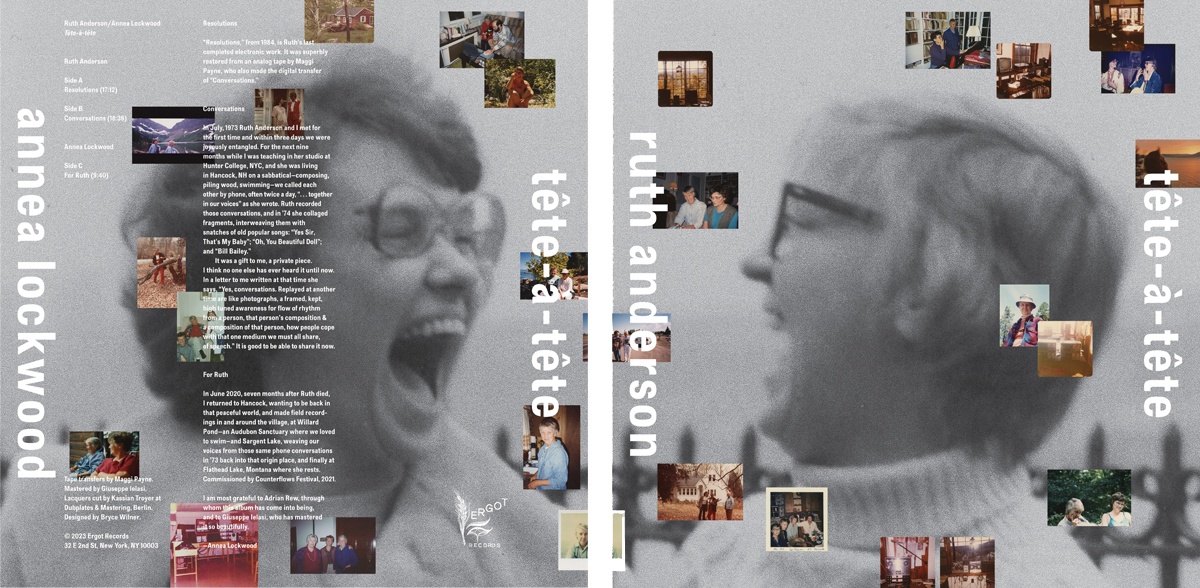

Tête-à-tête, by Ruth Anderson and Annea Lockwood, Ergot Records

• • •

One might not readily associate the early history of electronic music with uproarious laughter and whirlwind romance. Looking back at the black-and-white photos of powerhouse institutions of those years, like the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in 1950s New York, one sees imposing racks of equipment and stern-looking people, mostly men, in sharp suits and horn-rimmed glasses. Listen to their recordings, and the sounds seem just as serious. While the music could certainly be fun (in some sense of the word), fun was not generally the end goal.

Ruth Anderson giving a flute performance, probably early ’50s. Courtesy Annea Lockwood.

A few composers, though, broke the ivory tower wide open, bringing in popular culture and a sense of humor. One such artist was Ruth Anderson, who began her career as a flautist for orchestras, went on to gain renown as an accomplished arranger for television and theater, and ultimately became a devoted educator. In the 1960s, after spending some time at Columbia-Princeton, she was one of the only women in the world to lead an electronic music studio, which she founded at Hunter College in New York. She created riotous tape collages like DUMP (1970) and SUM (State of the Union Message) (1973)—which mixed otherworldly noises with raucous samples of contemporary media—as well as tranquil, elegant works like “Points” (1974), which was based on a series of sine-wave tones. Her recorded output, if relatively small compared to the large discographies of more famous contemporaries like Pauline Oliveros, is revelatory and forward-thinking.

Annea Lockwood and Ruth Anderson looking over a score in Crompond, NY, early 1980s. Courtesy Annea Lockwood.

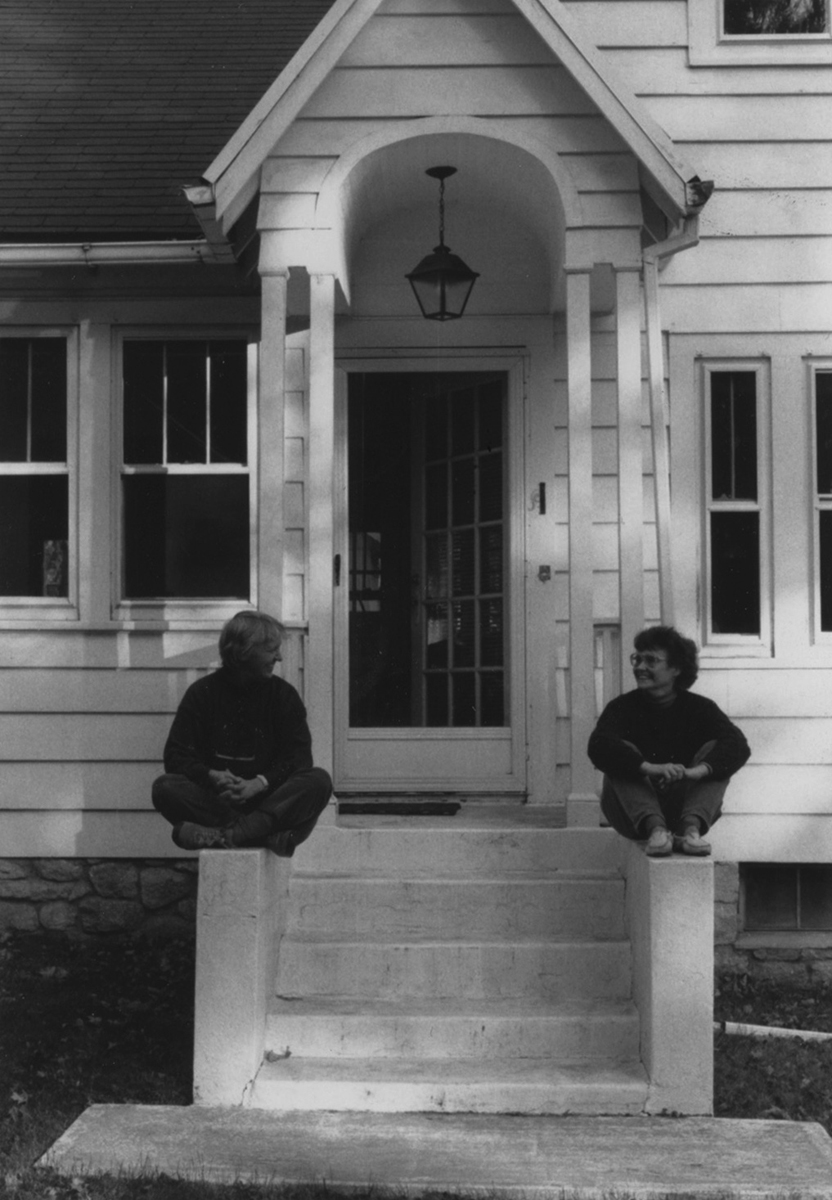

Anderson was also half of one of the most legendary power couples in experimental music; her longtime partner, Annea Lockwood, has been forging groundbreaking works for nearly six decades that involve everything from burning pianos and broken glass to sound maps of rivers. The recently released album Tête-à-tête combines posthumous work by Anderson, who passed away in 2019, at the age of ninety-one, and recent music from Lockwood, who is now eighty-three. It is a remarkable record—a dialogue between two composers falling in love with each other and a tribute to their relationship, which spanned close to fifty years.

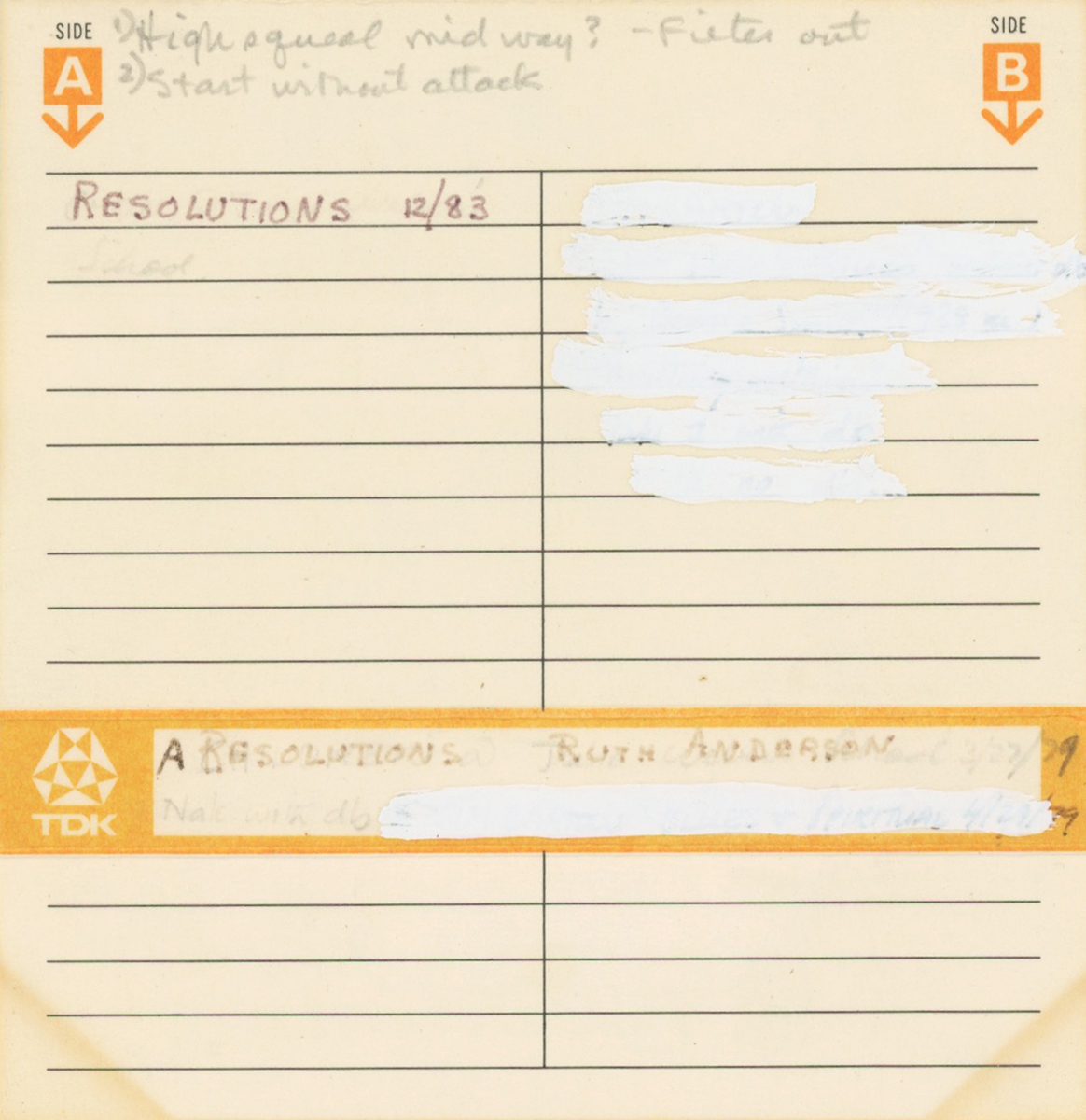

J-card for 1983 cassette sub master of Ruth Anderson’s “Resolutions.” Courtesy Annea Lockwood.

Tête-à-tête begins with “Resolutions,” Anderson’s last fully realized electronic composition, from 1984, a minimal seventeen-minute sine-wave meditation that gradually builds in intensity. The second and third tracks, “Conversations” and “For Ruth,” are among the strangest and most profound pieces of music I have ever heard. Anderson made “Conversations” for Lockwood in 1974, soon after the two first met, and it was never publicly released. It is a sample collage, much like SUM and DUMP, but the samples are culled from phone conversations between the new couple. Laughs, giggles, and breathy oohs and aahs are mixed with bits of old-timey tunes, like the 1925 hit “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” and the vintage ragtime song “Oh, You Beautiful Doll.” The first time I played “Conversations,” it felt slightly uncomfortable, like reading someone else’s private diary. You are quite literally eavesdropping on intimate snippets of other peoples’ personal lives. But after multiple listens, the mélange started to reveal its inner workings, showing the impetuous, headlong rush of love in its first bloom. There are thousands, probably millions of songs about love, but few of them have the crisply photographic quality of “Conversations,” documenting a nascent romance as it unfolds.

Annea Lockwood and Ruth Anderson in Glacier National Park, MT, 1990s. Courtesy Annea Lockwood.

The final piece, “For Ruth,” is Lockwood’s poignant homage to her late partner. In 2020, Lockwood made field recordings of sites that had held significance in their lives: Willard Pond and Sargent Lake in New Hampshire and Flathead Lake in Montana. The piece follows a chronology through its sounds of the outdoors: New Hampshire was where Anderson was living in the early days of their relationship; Flathead Lake was where they built a home, and is the location of Anderson’s final resting place. The piece gently travels through a geographical timeline of their life story.

Ruth Anderson and Annea Lockwood at their home in Crompond, NY, 1970s. Photo: Judith Rosen.

These aural captures of nature are peaceful, filled with the burbling sounds of water, wind, birds chirping, and insects humming. My cat, who is wise enough to tell the difference between a real bird and one on YouTube, perked up his ears in excitement when he heard this track, with its hyperrealistic, incredibly recorded menagerie of wildlife. Lockwood has, in the past, made intricate “sound maps” of the Danube, Hudson, and Housatonic rivers, and the sonic immersion of “For Ruth” is spectacular. You feel, as a listener, that you have been transported to those locations—not as a mere spectator but as an active participant. “There’s something I started writing about, about a year ago, listening ‘with’ as opposed to listening ‘to,’ ” the composer told filmmaker Sam Green, who made the 2021 documentary Annea Lockwood / A Film About Listening. “And it’s my sense that if I’m standing here, I’m just one of many organisms that are listening with one another within this environment . . . we’re within it, and we’re all listening together, as it were.”

Ruth Anderson’s studio in Hancock, NH, 1973. Photo: Ruth Anderson.

Interspersed throughout the rich ecological soundscapes are the occasional haunting metallic echoes of church bells and extracts from those heart-to-heart talks between Lockwood and Anderson. In a way, “For Ruth” is a conversation with “Conversations,” using fragments of telephone calls from the same time period. But now that Anderson has passed away, Lockwood, through sampling, communicates with her memory and her spirit.

Annea Lockwood and Ruth Anderson in Montana, early 1980s. Courtesy Annea Lockwood.

The most moving segment of “For Ruth” is the slow, drawn-out ending. Near its close, there are sounds from Flathead Lake, then dialogue from a 1973 recording. One can faintly hear Lockwood tell Anderson over the phone that it is time to go to sleep. “Good night,” Lockwood says. “I love you.” “Bye bye, darling,” Anderson replies. Through their unique shared musical language, Lockwood bids farewell.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.