Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Jazz and the Black critic: a new book reproduces notoriously hard to find issues of a revolutionary ’60s magazine.

The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, 1968–69, edited by Amiri Baraka, A. B. Spellman, and Larry Neal, Blank Forms Editions, 181 pages, $35; Cricket radio show available to stream here October 2, 2022, 9 am–5 pm

• • •

In his scathing 1963 essay “Jazz and the White Critic,” Amiri Baraka—then known as LeRoi Jones—protests against the predominantly white critical establishment: “Most jazz critics have been white Americans, but most important jazz musicians have not been.” He argues that jazz criticism, as it was then presented, “served in a great many instances merely to obfuscate what has actually been happening with the music itself.” His frustration ran deep as one of the only Black writers who was publishing on jazz in the ’60s, contributing to prominent magazines like Down Beat and Jazz Review. To redress the situation, he cofounded the Cricket with his friends and fellow critics Larry Neal and A. B. Spellman in 1968. A jazz magazine written entirely by Black contributors, the Cricket’s first issue put forth an assertive editorial that reads like a manifesto: “The true voices of Black Liberation have been the Black musicians . . . we propose a cultural revolution . . . no longer will we as Black Men allow the white sensibility to dominate our lives.”

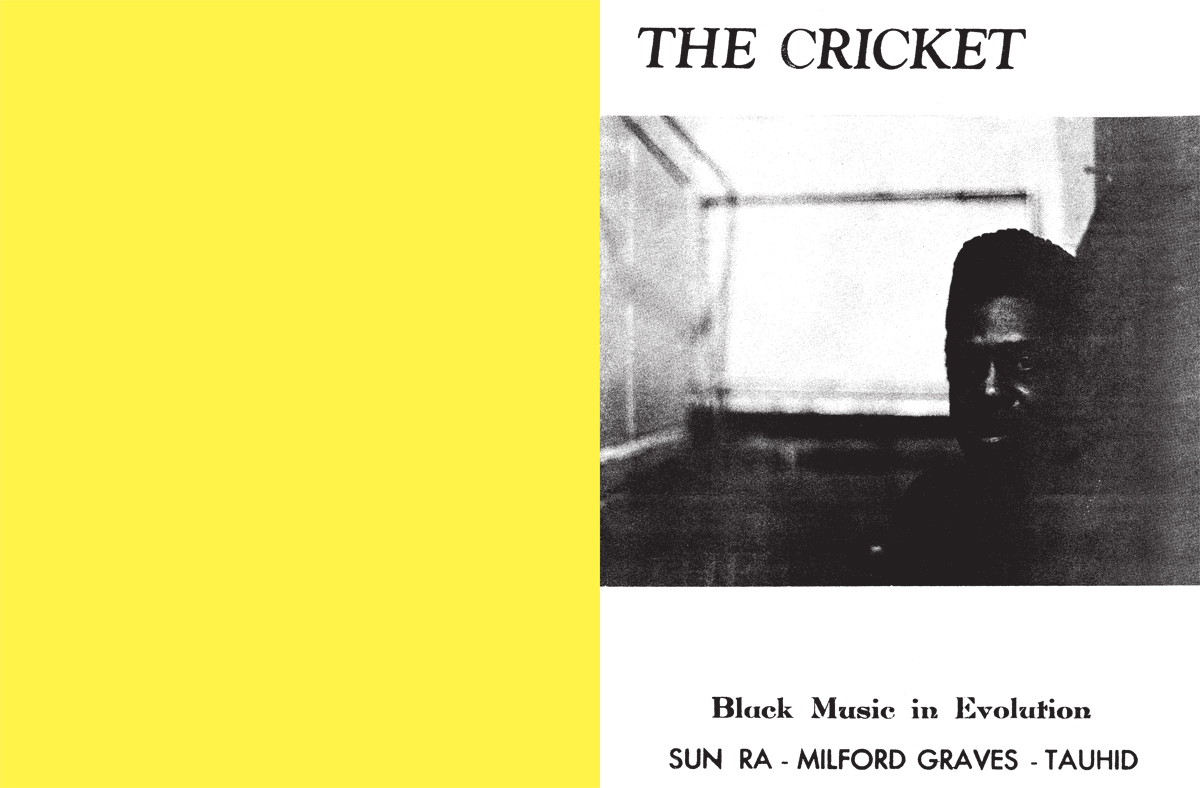

Cover spread from issue 1 of the Cricket, 1968. From The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, 1968–69, pages 20–1. Courtesy Blank Forms.

The magazine didn’t live long, publishing four times between 1968 and 1969. Notoriously difficult to track down for decades, each issue has now been reprinted in a complete facsimile published by Blank Forms Editions with an incisive preface by Spellman and a thoughtful new introduction by David Grundy.

From issue 4 of the Cricket, 1969. From The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, 1968–69, page 115. Courtesy Blank Forms.

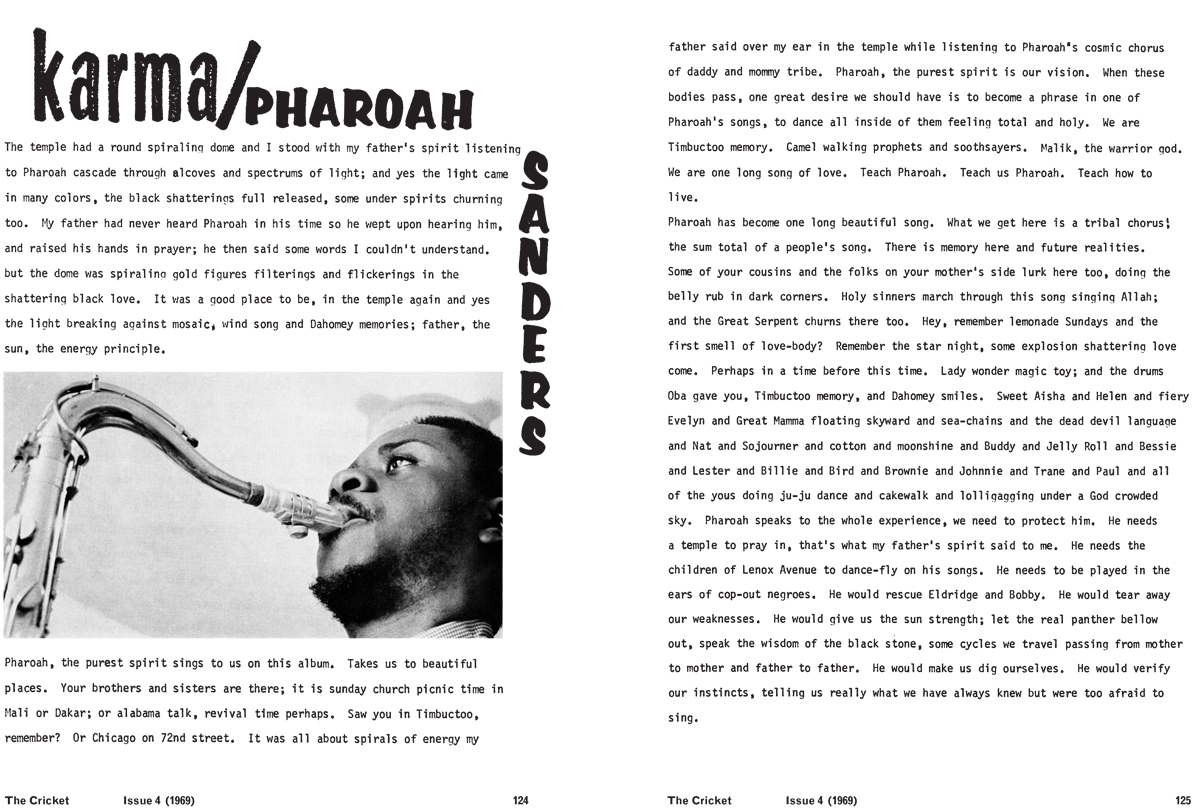

The Cricket was a product of its time. “By the late 1960s, many of the Black intellectuals and artists active in the era’s burgeoning arts scene found ourselves compelled by the Black Power movement rising in the South and the clarion that was Malcolm X . . . The cultural nationalism broadcast from the pages of The Cricket was youthful, a proto-ideology akin to but younger than the Garveyite movement and the separatism of Elijah Muhammad,” remembers Spellman. The magazine was charged with energy, featuring imaginative writing about jazz that mirrored the adventurous spirit of the music, all in a bracing and experimental style. Some of the pieces were poems, some were personal essays, some were impassioned political statements. James T. Stewart published a position paper with the title “Revolutionary Black Music in the Total Context of Black Distension.” A four-page essay by free-jazz percussionist Milford Graves was printed in all caps. Record reviews abounded, but none resembled standard music-magazine fare. One example, on a new Impulse Records album, begins: “I heard this once each side. It’s bullshit.” A dreamlike review of Pharoah Sanders’s 1969 album Karma reads in part: “Clouds passing above. A few stars. Spotlights across the sky. The sound: Shooting stars, whirling galaxies of sound. Expansion.” The tone was often conversational, dispensing with the usual formalities and faux objectivity of mainstream arts criticism.

Spread from issue 4 of the Cricket, 1969, pages 6–7, with Larry Neal’s review of Pharoah Sanders’s album Karma. From The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, 1968–69, pages 124–5. Courtesy Blank Forms. Photo of Pharoah Sanders by C. Daniel Dawson.

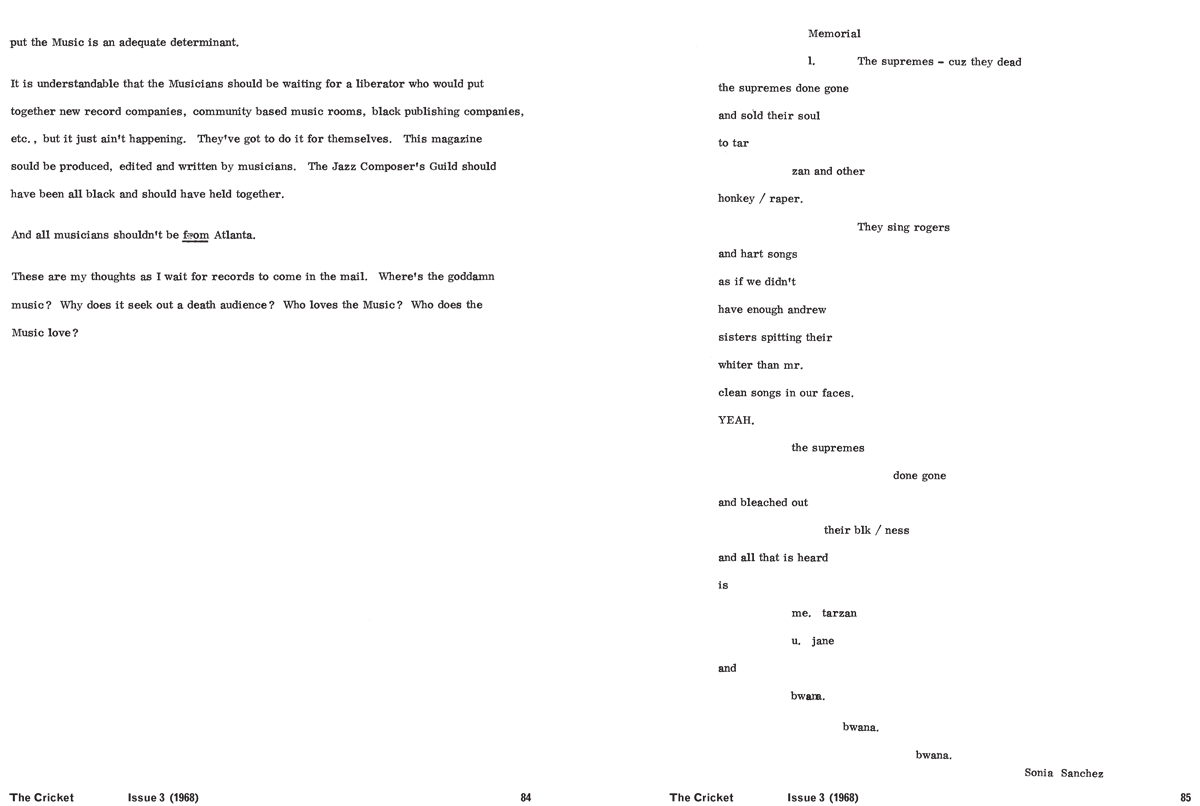

The Cricket was an underground sensation—those who read it were extremely enthusiastic, even if circulation was modest, at five hundred copies or fewer per issue. In contrast to Down Beat’s slick photography and copious advertising, it looked like a scrappy homemade zine, and in fact it was printed on a mimeograph machine at Baraka’s home base of Newark, New Jersey, on a shoestring budget. But the Cricket didn’t need conventional production values or professional slickness; it had ideas and vision in spades. The roster of contributors was impressive: several, including Spellman and Neal, were leading figures in the Black Arts Movement, while others were legendary avant-garde jazz musicians, composers, and improvisors, including Sun Ra, Milford Graves, and Albert Ayler. They were eloquent writers, with voices as unique and distinctive as their music. However, it must be noted that women were largely absent from the lineup: a poem by Sonia Sanchez is a rare exception. If the Cricket had continued beyond four issues, one would hope this situation would have been rectified.

Spread from issue 3 of the Cricket, 1968, pages 7–8, with Sonia Sanchez’s poem “Memorial” on right. From The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, 1968–69, pages 84–5. Courtesy Blank Forms.

There was tremendous geographic diversity in the Cricket, though; the magazine extended its view far beyond the East Coast scene, the traditional focus of many jazz narratives. In a long and intriguing dispatch from Los Angeles, critic Stanley Crouch, in a discussion of the pianist and bandleader Horace Tapscott and the Community Cultural Orchestra, decries the New York–centrism of mainstream media. Another issue includes an intricate letter from Atlanta examining the local music scene; there’s also a dispatch from Detroit’s east side. The final issue includes a report from apartheid South Africa detailing the many financial hardships faced by musicians there. Sun Ra expanded the Cricket’s geographic focus even further to include the entire universe. In a poetic essay titled “My Music is Words,” Ra writes on the early inspirations for his music and his hopes for a better future. “Freedom to me is the freedom to rise above the cruel planet,” he muses, before ascending to what he calls the “infinity universe.”

Cover spread from issue 3 of the Cricket, 1968. From The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, 1968–69, pages 74–5. Courtesy Blank Forms.

Could something like the Cricket exist today? As a critic myself, I felt a rush of excitement that people cared enough about music, and about criticism, to put together an entire publication responding to the problems inherent in the music magazines of their time. Flipping the pages of this fierce, mimeographed maelstrom of ideas, one feels an invigorating cultural conversation taking place—not just between the Cricket and Down Beat, but between the writers in its pages, and the past, present, and future of music.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.