Mark Dery

Mark Dery

In Jeff Sharlet’s new book, a heartbreaking narrative of the disintegration of the US through frontline reportage on far-right extremism.

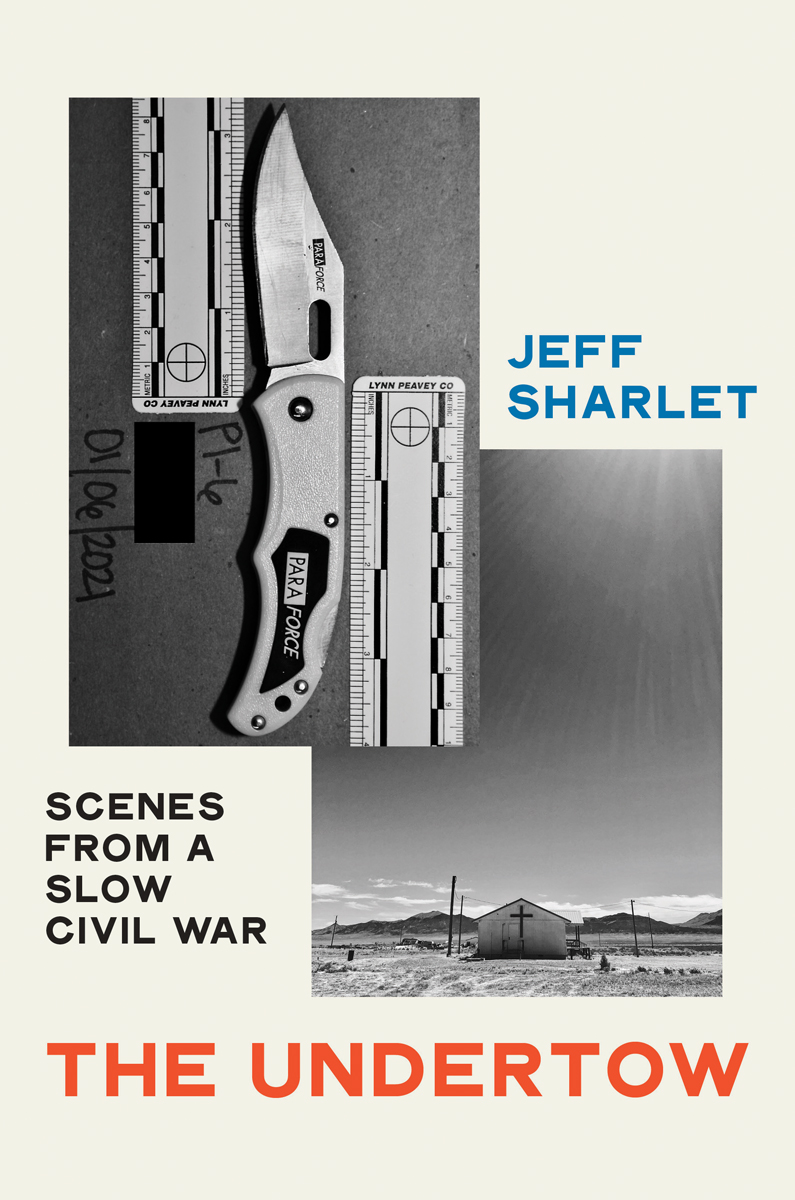

The Undertow: Scenes from a Slow Civil War, by Jeff Sharlet,

W. W. Norton, 337 pages, $28.95

• • •

In 2007, Jeff Sharlet was alone in a cabin in the woods—horror fans know this won’t end well—reading Jonathan Edwards’s A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton (1737). Edwards, the Puritan divine best known for his hellfire eloquence in Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God (1741), was a firm believer in the “preaching of terror.” Sharlet, an agnostic Jew known for his immersion reporting on the Religious Right, was duly terrified.

In The Family (2008), his investigative thriller about an elite cabal of Christofascists that counts Mike Pence and Senator Chuck Grassley among its members, Sharlet reads A Faithful Narrative as Puritan Gothic. In his telling, Edwards’s God is a monster of moral depravity who commands a pure-hearted parishioner named Abigail Hutchinson to starve herself to death, her sinful flesh an offering to religious mania. “God is my friend,” she whispers through parched lips as she dies, her face taut-stretched across her skull, a living death’s head.

Fatefully, even Edwards was “ill prepared for what the new believers—fiercer in their faith than ever Puritans had been—would build,” writes Sharlet. The Great Awakening whose flames he whipped up was only the first of many revivals that would give American Christianity its evangelical cast. That fundamentalist fervor would make our New Jerusalem, where beginning anew is synonymous with being born again, congenial to the madness of crowds and the schemes of powerful men. America is and always has been an “imaginary place,” says Sharlet, yet one that’s “so real in the minds of those for whom religion, politics, and the mythologies of America are one singular story.”

In his latest book, he fishes where those cultural rapids run together. The Undertow: Scenes from a Slow Civil War is a collection of frontline dispatches from what Pat Buchanan, the Jonathan Edwards of Nixonland, once called the “war . . . for the soul of America,” a “religious war,” he thundered, but a cultural one, too. Empty and aching, like the narrator of Paul Simon’s “America,” Sharlet drives cross-country, from a Sacramento rally for the insurrectionist martyr Ashli Babbitt to his home in Vermont, searching for the answer to Trump’s American carnage but equally for indelible images, pungent phrases—the stuff of myth—that will give shape to his own grief as well as “the grief that is in us all now,” a heartsickness born of “the passing of certain possibilities—democratic, ecological— . . . which we still speak of in the present tense, as if they’re not already gone.”

At the Justice for Ashli Babbitt rally, he listens to a former TV host named Jamie Allman, for whom the sacking of the Capitol on January 6 was “one of the most beautiful days I’ve seen in America,” extol what Sharlet calls “the mythical victimhood of a White woman, killed by a Black man.”

In the ironically named Church of Glad Tidings in nearby Yuba City, he hearkens to Pastor Dave Bryan—Trump disciple, COVID truther, subscriber to the conspiracy theory that Biden stole the election, superfan of the kickass Jesus of Muscular Christianity—preaching from a pulpit made of swords, right out of Game of Thrones.

At a Trump rally in Sunrise, Florida, he talks to Diane G., a true believer with “ice-blue eyes . . . so large she seemed to sparkle when she smiled.” “Trump is not my God,” she insists. Nonetheless, “God put him there,” using him as an instrument of divine wrath in the “spiritual war” against the wickedness of an America that has lost its way, led astray by evildoers like the Clintons. “It was too terrible to speak of,” Sharlet tells us, channeling Diane. “ ‘The truth and the lies,’ she said. I didn’t know what she meant. . . . ‘I’m going to say it,’ she decided. But she couldn’t. She walked off. Her friends were worried. She came back. ‘They eat the children.’ The Clintons, she meant. She shook with tears. Her friends nodded.”

Sharlet once told an interviewer that the recording angel in the Book of Malachi had his “dream job.” In The Undertow, he records the stories of white supremacists, Christian nationalists, red-pilled men’s-rights misogynists “joking around about rape with a young woman they’d never met before in a hotel room after midnight,” conspiracists who see in Trump’s invisible-accordion gestures “the air Q” (for QAnon) and who use “the kabbalistic discipline of alphanumeric codes known as gematria” to unriddle Trump’s tweets by converting their emphatic capital letters into numbers.

In Trump’s America, narratology times demonology equals eschatology, the violent rapture of the civil war so many of them are eagerly prepping for. “We need to separate by red states and blue states,” Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene just tweeted, as I write this. “From the sick and disgusting woke culture issues shoved down our throats to the [sic] Democrat’s traitorous America Last policies, we are done.”

Sharlet, who teaches creative nonfiction at Dartmouth, surely knows, as every journalism prof does, the Didion quote from The White Album (1979): “We tell ourselves stories in order to live . . . We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five.” Trouble is, suicides don’t lend themselves to homilies, and few homicides, in this murderously violent land, hold moral lessons.

Maybe that’s the problem. The Undertow feels at once urgently important and inconclusive. Perhaps we’ve realized, at long last, that sermons and parables, from Edwards to Trump, won’t save us. In fact, they just might be the death of us.

Didion begins her essay collection Slouching Toward Bethlehem (1968) by saying that she’d “been paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act” at a historical moment when everything was flying apart and the center seemed as if it couldn’t hold. Now, over a half-century later, the chaos is the center: “the politics of the fringe may not be rational, but they’re cunning,” writes Sharlet, “surrounding the center and moving inward, until suddenly there they are, at the heart of things.”

He quotes David Straight, a guest speaker at the Church of Glad Tidings, who, “like adherents of the QAnon conspiracy theory and its spin-offs, called what was happening now a ‘Great Awakening.’ ” Straight “was no [Jonathan] Edwards,” says Sharlet, “but the revival of which he and the martyr Ashli were part—‘#TheGreatAwakening,’ as Ashli tweeted—was not so much aberration as the continuity of feverish dreams twisting through the American mind since the beginning.”

Equal parts Hawthorne and Poe, Edwards’s vision of a theocracy cleansed by the fires of revival looks, in retrospect, like an augury of MAGA Nation, mad for God and hell-bent on moral renewal, preferably at the business end of an AR-15. Judgment Day is coming, Brother Straight assures the faithful. He exults at the thought of mass executions, a reckoning for all who refuse to “stand up” for God. Soon enough, we’ll know “who was standing, and who was not,” he prophesies, “and who, in the coming freedom, would dangle.”

Sharlet tells Straight’s story and others like it, tells them with a poet’s gift for synesthesia (“her voice was like old silver”), a wit so understated it’s barely there (“Pastor Rich . . . attended to the soul, such as it may be, of Justin Bieber”), a hangman’s knack for giving his subjects just enough rope. Harrowing, heartbreaking, scary, but also bleakly funny in a theater-of-the-absurd way, The Undertow is a Wisconsin Death Trip for the Trumpocene, a graveside elegy on the edge of the burn pit that used to be—if only aspirationally—a democracy.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and the author of four books, most recently, the biography Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. He has taught journalism at NYU and “dark aesthetics” at the Yale School of Art; been a Chancellor’s Distinguished Fellow at UC Irvine and a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy in Rome; and published in a wide range of publications, from the New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, and Wired to Cabinet, Hyperallergic, and the LA Review of Books.