Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Barthes and Brexit: a novel by Xiaolu Guo.

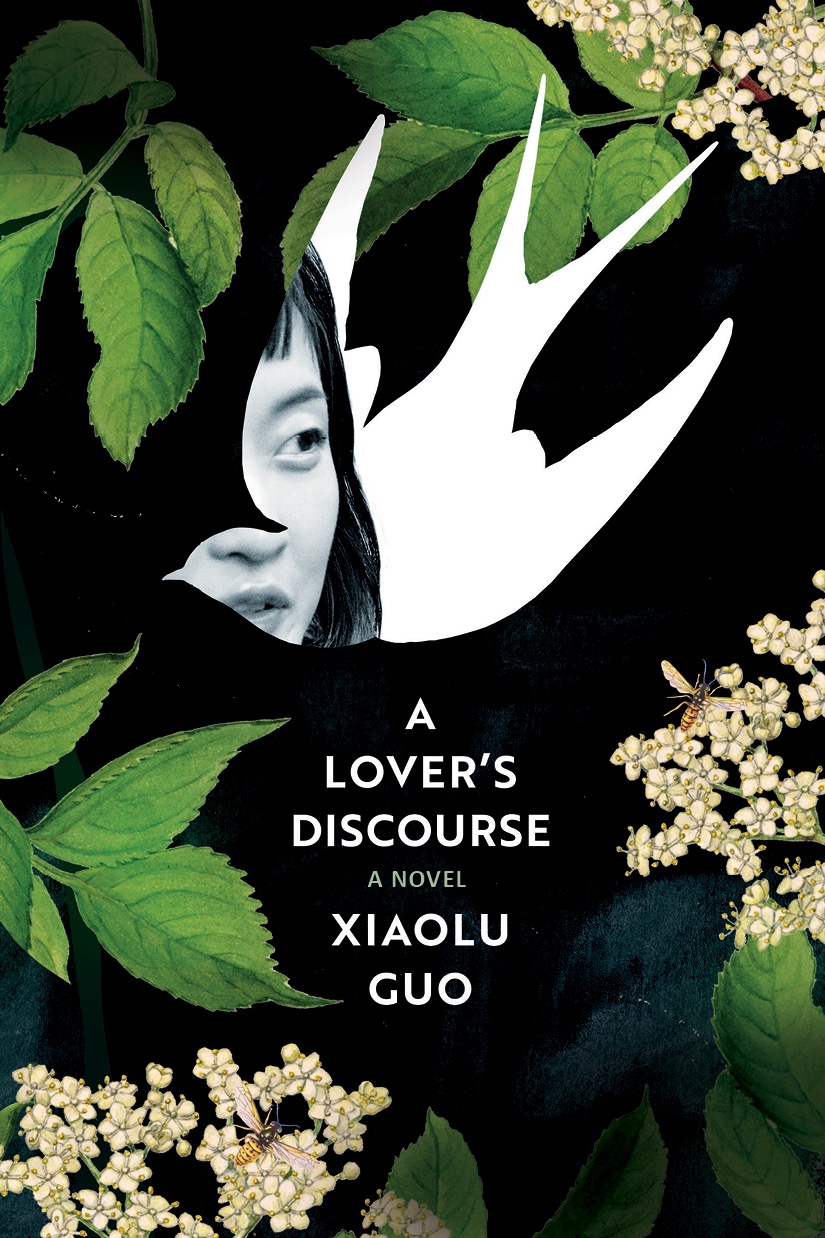

A Lover’s Discourse, by Xiaolu Guo, Grover Press, 271 pages, $26

• • •

The Chinese writer and filmmaker Xiaolu Guo moved to London in 2002, and has lived there or elsewhere in Europe ever since, producing work—both fictional and documentary—that is all about identity and exile, home and elsewhere (and maybe home as elsewhere). A Lover’s Discourse is Guo’s seventh novel, and the fifth she has written in English. It’s a witty, melancholic answer to a question that lurked and vexed until this year’s more alarming events took over: Who will write the novel of the UK’s Brexit calamity? In light of the movements of global trade, power, information, and people, it’s no surprise that one of the candidates should be a Chinese novelist whose narrator is a Chinese anthropologist, trying to make sense of this damp nostalgic corner of Europe—or not Europe. But the place won’t give up its meanings easily: A Lover’s Discourse is a fragmentary, ironic study in fragmentary, innocent experience. This novel takes its title from Roland Barthes for good reason: it’s as much about desire and fantasy as analysis or comprehension.

The nameless female protagonist arrives in London in December 2015, six months before the Brexit vote, of which she has no inkling, or much understanding when she starts to hear about it. “I had no idea there would be a referendum. I vaguely knew this word in a Chinese context. But in China we never had such an experience.” At first she is friendless, disinclined to watch soccer in rowdy pubs, confounded by the poverty that surrounds her in a supposedly well-off Western city. She wanders the banks of the Regent’s Canal, looking for bucolic refuge amid all the gray, and thinking about her parents, lately deceased. Embarking on her doctoral research, concerning a village back in China that produces most of the world’s painted replicas of Western old masters, she claims not to believe in artistic originality—a fetish of academic “old farts”—but in life she’s obsessed by authenticity, by the question of where and how to live. (“I wanted to be a woman in the world”—hence her choice of a university so far from the Chinese locus of her research.)

Guo is a savvy observer of the version of itself that London presents to the likes of her narrator. The young woman finds herself in the gentrifying district of Dalston: “For people like me from China or other countries that have only recently escaped poverty, the sight of poor people barging into each other in a chaotic market with rats running around and fish rotting on the pavement was not that ‘trendy’.” She lives among drab concrete social housing, “the kind I would not regard as nice, as the English would say.” When good things are not nice, according to middle-class Londoners, they are lovely—but gentility fails to hide the grimness of British life as the economic storm of Brexit approaches. Are things really that simple? The narrator’s view of the city, and the nation beyond, is distant, caricatured, and riven with cliché. She has no actual idea where the politics of Brexit come from, and when she travels by train to Scotland she sees only “sad little towns” on the way. Still hampered by the exile’s self-protection, she hasn’t yet grasped that there is any there there.

Meanwhile, a shadowy “you,” also unnamed, has been the addressee of this story, and now makes himself present, after a fashion. She meets him in a park, and again at a book group: a landscape architect born in Australia and raised in Germany, who in time persuades her to live with him in a boat on the canal. “I was not sure how I would feel, if the ground beneath my feet swayed a little every day.” Their relationship is consoling but fraught: they spend a good deal of time arguing about how much material comfort a life today should involve, the boyfriend (later husband) aiming for a simpler, even rural, existence, and the narrator caught between her eagerness for the city’s energy and her longing for Chinese landscape. At times, this aspect of their romance devolves into a slightly stagy, awkward faceoff between brutalist design—de rigueur reference in contemporary London—and supposedly humanist pastoral. It culminates in the Scottish trip, to the supremely kitschy Garden of Cosmic Speculation (a real-life monstrosity designed by architect and theorist Charles Jencks).

The subtler aesthetic-emotional argument in the book is about Barthes, and the versions of love his writing implies. A Lover’s Discourse (1977), Barthes’s essayistic anatomy of desire’s lexicon, is the protagonist’s favorite book. She dislikes Balzac, Dickens, and Hemingway: “Only when I found paragraphs that carried a sense of the defeated, the ignored and the dying did I feel connected.” Barthes, she says, writes like a woman who cannot stop talking—his eloquent vulnerability, especially in his late writings about his mother, sustains the displaced anthropologist, emotionally and intellectually. It informs the novel too: Guo borrows Barthes’s tentative, laconic use of short, titled chapters with enigmatic epigraphs, the narrative parcelled up in precious interludes. Still, the narrator is not exactly at home in Barthes’s work: she had thought A Lover’s Discourse was a book about men and women, and is startled when her partner reveals that Barthes was gay.

The geographical scope of the novel expands beyond fretful Britain: the woman and her (now) husband travel to Italy for their honeymoon, to Australia and Germany to meet his family. They even try to make an agricultural life on a patch of wasteland in Lower Saxony. Along with the canal-boat adventure, some of these peregrinations in search of a home seem rather too convenient for a story about exile and belonging—also, where does the money come from?—but they lead to an essential question: “So, art is gone, home is not working, what is there left for me to hang on to?” Is it possible, when it comes to countries or continents, simply to love the one you’re with? If that seems simplistic, it’s also, both in this novel and in the real Britain it describes, a pressing political dilemma for the more privileged immigrant: Can you commit to staying in, and helping improve, a country determined to say no to its neighbors?

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence was published in September by New York Review Books. In Pieces: essays on art, etc. will be published in 2021 by Sternberg Press.