Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

A new reissue of Claude Cahun’s 1930 “anti-memoir,” accompanied by photomontages made with their partner Marcel Moore.

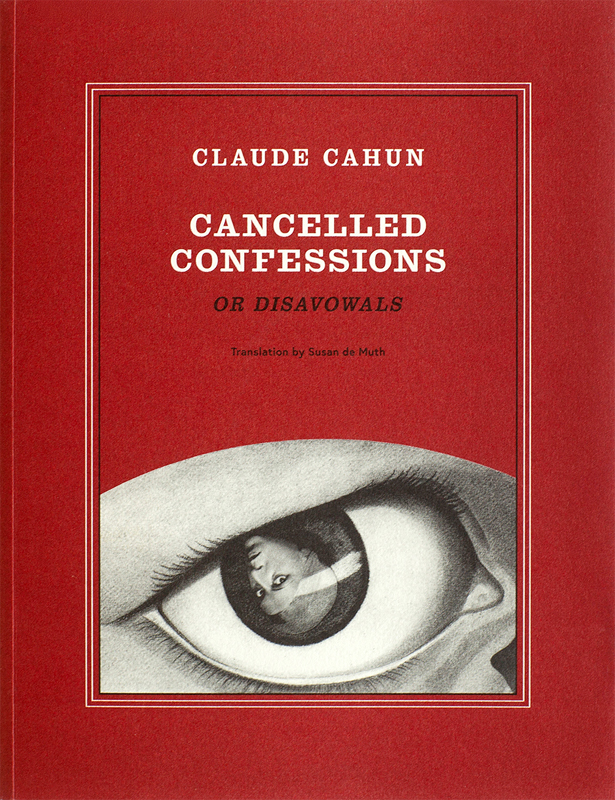

Cancelled Confessions (or Disavowals), by Claude Cahun, translated by Susan de Muth, Siglio, 254 pages, $36

• • •

With the serial self-inventor born Lucy Renée Mathilde Schwob in 1894, there is first of all the matter of pronouns. From 1913 until the French artist-writer’s death in 1954, the always-alliterative Claude Cahun contrived a photographic and prose (or is it poetic?) body of work treating gender as travesty, sham, private theater, and futuristic vision that could only be fulfilled later in the century, with collective will and imagination. Cahun self-identified as “Uranian,” a sexological term for homosexual that was already old-fashioned, redolent of the decadent 1890s. In Cahun’s early photographic works, there are versions of prior fashions in sexual ambiguity: self-portraits seemingly in the guise of fin-de-siècle male dandies, as austerely costumed avatars of Beau Brummell and Charles Baudelaire. Also, got up like a shaven-headed cousin to the sharp-suited Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. In life, Cahun did not adopt a nonbinary identity, but there are good reasons to do as critic Amelia Groom does in her afterword to Cancelled Confessions (Aveux non avenus)—Cahun’s 1930 “anti-memoir,” newly reissued by Siglio Press—and say they/them. Everything is further complicated by the fact that Cahun’s artistic work was made with their partner, Marcel Moore—who was also their stepsister, née Suzanne Malherbe. Nowadays we might say: two artists and one practice, they were a third-sex double act of giddying equivocality.

By 1930, Cahun was a face, or many faces, in Paris among the brilliant sorority of lesbian modernists. They and Moore were friends with Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company, and Gertrude Stein in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas mentions having met Cahun. With their Expressionist suits, their monocles, and their cropped hair, sometimes dyed pink or gold, Moore and Cahun were sufficiently outré that they could drive the prudish Surrealist kingpin André Breton out of a café simply by showing up. Cahun, having studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne, was writing for cultural magazines and philosophical journals; an earlier book, Héroïnes, was completed in 1925, consisting of proto-feminist monologues by famous women of legend and fiction, from Eve and Penelope to Cinderella and Beauty from La belle et la bête. The autobiographical Cancelled Confessions was solicited first by writer and publisher Adrienne Monnier, who was also Beach’s lover and bookselling competitor across the street on rue de l’Odéon. In a 1926 letter, Cahun promised a confession “without deceit of any sort,” and two years later delivered a manuscript (partly collated from things already in print) that even Monnier, apostle and patron of the avant-garde, balked at publishing. Eventually, five-hundred copies were issued by the left-wing publisher Éditions du Carrefour.

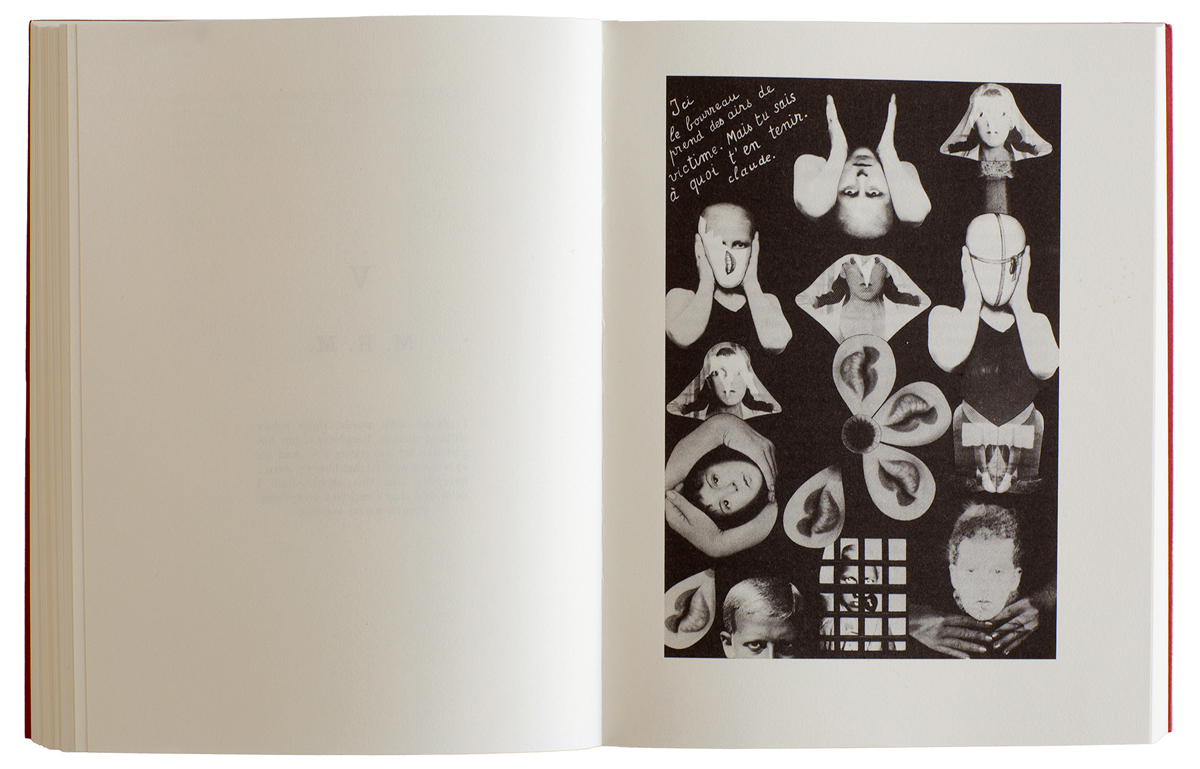

Spread from Cancelled Confessions (or Disavowals), Siglio, 2025. Photomontage by Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, originally published in Aveux non avenus by Éditions du Carrefour, 1930. Courtesy Siglio.

From the title onward, it’s a hard work to fix in genre, style, or memoiristic import. Susan de Muth’s translation first appeared in 2007, when Aveux non avenus was rendered as Disavowals. In the translator’s note of this retitled edition, de Muth describes “Cahun’s liberal use of colloquialisms, aphorisms, puns and wordplay.” All of which starts on the title page—“Cancelled Confessions” maintains at least some of the author’s love of alliteration, assonance, textual doublings that mimic in turn the mirror world of Cahun’s (and Moore’s) life and imagination. The opening pages already suggest a fun-house text, “the most ludicrous merry-go-round.” If this is to be an autobiography, it will be a life and language of dizzy lure and omission: “Should I then burden myself with all the paraphernalia of facts, stones, cords delicately cut, precipices . . . It doesn’t interest me at all. Guess, recover. Vertigo is implied, ascension or the fall.” As in some of their art, there’s a will from the outset to abstract the self, disappear into the ether, disavow the body—a textual urge not unrelated, it seems, to Cahun’s anorexia. “I’ll trace the wake of vessels in the air, the pathway over the water’s, the pupils’ mirage.”

Spread from Cancelled Confessions (or Disavowals), Siglio, 2025. Courtesy Siglio.

Form, Groom writes, is “all over the place” in Cancelled Confessions. True, the book moves with delirious energy from one mode to another—stories, essays, dialogues, portraits, spiritual or metaphysical disquisitions. There are shards of sense, almost sentences: “Fast and Good. Short but sweet. . . . Anxious dawn. . . . Guillotine window.” Aphorisms that seem to be spoken by Cahun, or from a variety of named and nameless avatars. “There are people who would make you sick with their ugliness.” “It’s infuriating that one can only offer what one has, what one is.” “The great question is not: Does it have a purpose?—but: Does it add anything?” You could put this last query to Cahun’s text itself, in lieu of looking for sense, and say: it adds (to their oeuvre, to experimental prose in the era of Surrealism, to the sabotage of gender) an extraordinary collection of images. There is the “imprisoned wasp which knocks at the walls of my breast.” The mirror as symbol of capture and release. And the book’s most comical conceit: “Human body. It should be stuck upside down in a vase so that it arranges itself elegantly, so that it blooms, so that it has four branches, four flowers and the bulb is hidden.”

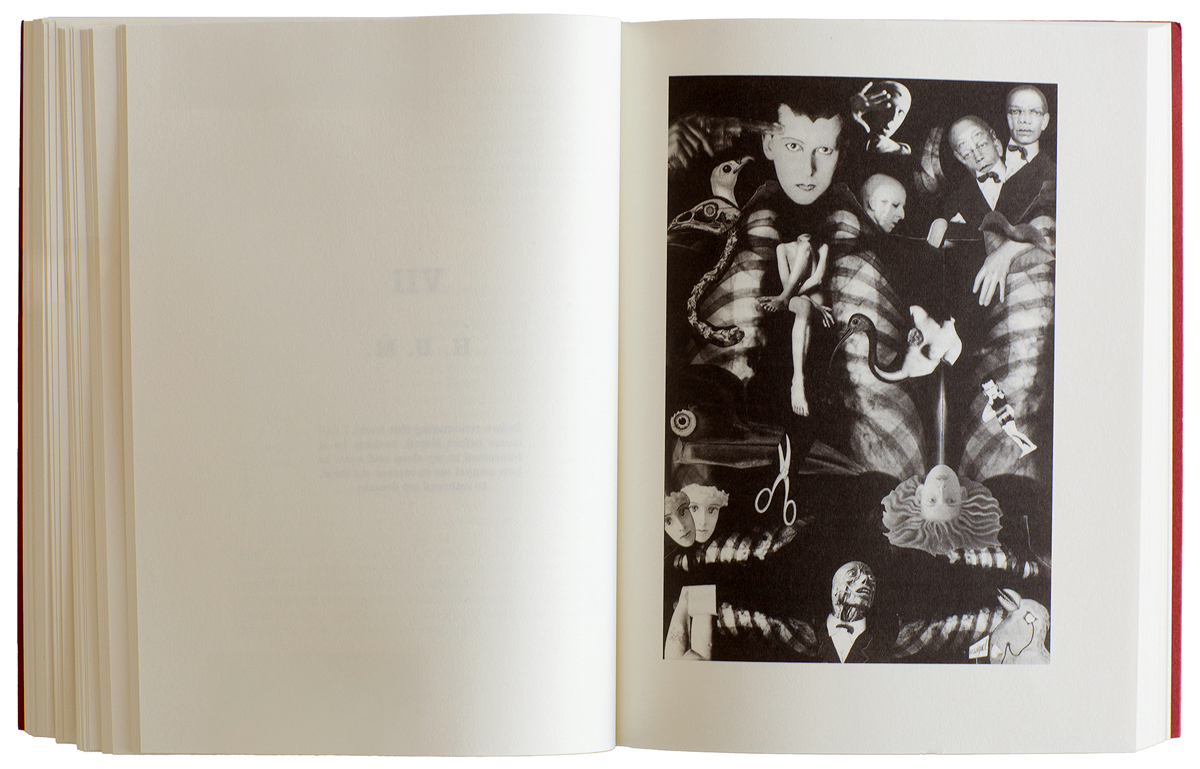

Spread from Cancelled Confessions (or Disavowals), Siglio, 2025. Photomontage by Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, originally published in Aveux non avenus by Éditions du Carrefour, 1930. Courtesy Siglio.

As in the 1930 original, Siglio Press’s beautiful edition is illustrated with ten photomontages by Moore, incorporating some of the well-known photographs the couple made together. For decades these were misidentified as self-portraits solely by Cahun, who is their most prominent subject. Here is the artist’s shaven head five times in one montage: two pairs joined at the shoulders like Siamese twins, and another one peeking from above as a curious or protecting angel. (In this image, Cahun resembles nobody so much as David Bowie playing Thomas Jerome Newton in The Man Who Fell to Earth, at the moment he peels off hair, eyebrows, and nipples to reveal his alien identity.) Elsewhere, Cahun is sliced into anatomical fragments—torso, limbs, eyes, lips, and X-ray ribs—or tricked out as an androgynous weight lifter, as blond-plaited Elle in a stage version of the tale of Bluebeard, or as a mystery-play Satan with double-decker eyebrows and a jeweled helmet. Moore’s montages at times resemble those of contemporaries like Hannah Höch or John Heartfield, but the most striking thing is their frequent symmetry and repetition, the way the various Cahuns array themselves like wings on the page. Becoming birds, becoming statues, becoming multiple.

Brian Dillon’s books include Affinities, Suppose a Sentence, Essayism, and In the Dark Room. His memoir Ambivalence will be published in 2026 by New York Review Books. He is working on a novel, Charisma.