Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

The writing Irish: Colm Tóibín examines the fathers of

Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce.

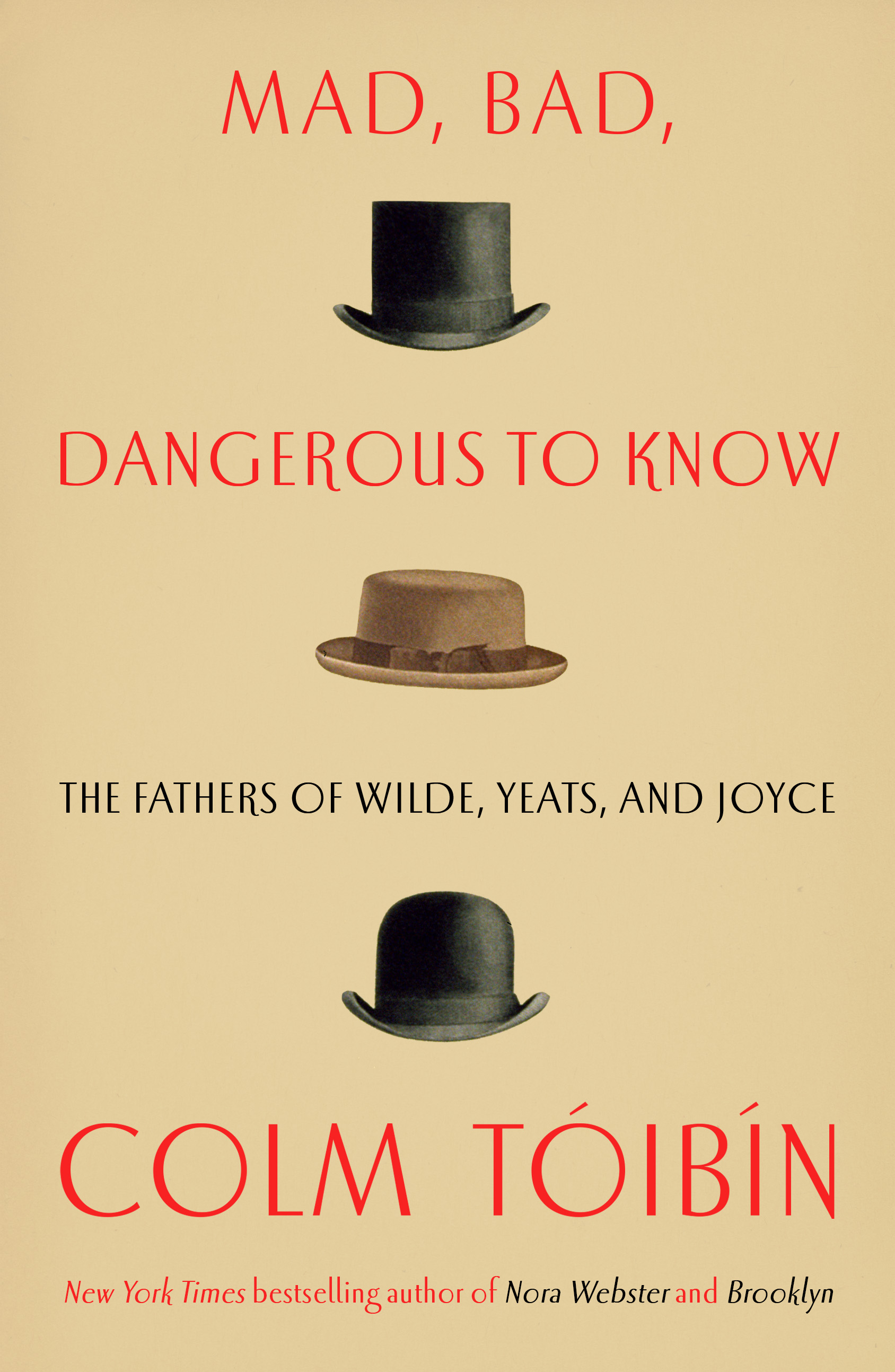

Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know: The Fathers of Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce, by Colm Tóibín, Scribner, 253 pages, $26

• • •

The celebrated Irish writer Colm Tóibín has been focused on women of late—from his short study of Elizabeth Bishop to a play and novel about the Virgin Mary. And so in some ways his new book comes as a surprise: a triptych of essays about the fathers of Oscar Wilde, W. B. Yeats, and James Joyce. Why these fathers, and why now?

One simple answer is that the American scholar Richard Ellmann wrote ground-breaking biographies of all three Irish writers, and Tóibín is engaged in a deeper archaeology of those lives. (The book began life as three contributions to the Ellmann Lectures at Emory University.) But the more interesting possibility is that now is the time for Tóibín to turn his attention to—what, exactly? Not quite, or at least not in all cases, “toxic masculinity.” Rather some combination of authority and vulnerability that says a good deal about how all three writers needed to reject or recast the versions of being a man that their fathers gave them. Which is perhaps a perennial subject, but seems to have a special resonance at a moment when prominent instances of male violence, narcissism, or simple irresponsibility are under scrutiny.

The first thing the three fathers did was fashion demanding legacies. In terms of sheer paternal accomplishment and its fretting effect on a son, Oscar Wilde had most to contend with. (And not only from his father: Wilde’s mother, Jane Elgee, who wrote under the pen name Speranza, was a well-known poet and a polemicist for Irish freedom.) Sir William Wilde was a prominent physician, who founded a hospital and gave his name to a pioneering ear operation. He wrote books about his travels in Europe and the Middle East, conducted important research into the antiquities and natural history of Ireland, and developed statistical methods that influenced census-takers around the world. His home was among the brightest literary salons in Dublin, though visitors noted that the person of their host was usually filthy. George Bernard Shaw later quipped that Sir William was “Beyond Soap and Water, as his Nietzschean son was Beyond Good and Evil.” Less comically, Sir William seems to have had an affair with a patient, Mary Travers, whom he and his wife then worked hard to keep quiet; she won a libel case against them in 1864.

Oscar Wilde was proud of his parents’ contribution to Irish culture—as Tóibín puts it, they conjured “a dream nation of traces and fragments”—but it’s striking how much of his own life and work are about aspirations to orphanhood, a state of glittering self-invention. In the case of John B. Yeats, painter father to the poet, the struggle seems to have been reversed: the father struggled to edge from the shadow of his celebrated son. Actually, scratch that: John B. Yeats never worked hard in his life, at least not at his art, for which he abandoned a career in law and neglected his family. Conversation, the curse of many Irish artists and writers, was his real calling: studio chat, and some winningly scurrile correspondence. While W. B. Yeats complained of John B.’s “infirmity of will,” and embraced the industriousness of his mother’s family, his father declared that “Willie has a doctrinaire kind of mind.” The elder Yeats rejected his son’s grand Celtic mysticism and occult interests, and instead focused on more modest ways of seeing. His letters bristle with epigrams and small manifestos for his idiosyncratic brand of impressionism. In old age, still hoping for success as a society portraitist, he moved to New York (“old men are popular here”) and spent a decade in his boarding-house studio, almost bereft of clients and trying to perfect a single self-portrait. “Actions,” he wrote, “are a bastard race to which a man has not given his full paternity.”

Joyce’s is the most vexed story of the three, the most convincing case that literary fathers are there to be slain. Readers of Ulysses will know John Stanislaus Joyce as Simon Dedalus, father of Stephen. The character has some of the choicest language in the book—“Shite and onions!” he exclaims at one point—and in real life, according to his son Stanislaus, exercised “a varied and fluent vocabulary of abuse.” He was also a drunk and “a man of absolutely unreliable temper” who once tried to strangle his wife, before James dragged him off. And yet in most of his son’s work he is not a monster. Tóibín conjectures that James Joyce may not have been so marked by the father’s rages as his siblings were, but also that exile may have blurred his view: he is notably more judgmental in Stephen Hero, a trial run at A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, than he is in Ulysses. Still, as a mature writer he no longer wanted anything to do with his chaotic and tyrannical father: John Stanislaus Joyce died alone with nothing to his name but a suit of clothes and a copy of his son’s play, Exiles.

A diverse trio, then. What links them—and makes of Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know something more than an exercise in literary biography—is a sense that a whole historical period, roughly that of modernism, had turned against fathers and all they stood for. (Theodor Adorno, later in the twentieth century, wrote: “The relationship to parents is undergoing a sad, shadowy change. They have lost their awe through their economic powerlessness.”) In Joyce’s case, this ultimately meant rejecting male rage and overweening will for the riverine, adventuring voice of Molly Bloom. For Wilde it entailed an impossible repudiation of straight patriarchy—he failed, or refused, to conceal his homosexuality, in art and life—which then pursued him to prison, exile, illness, and death. The Yeatses seem an anomaly. The father, for all his failings, appeared a curiously blithe and youthful figure in old age, and far more sympathetic than his son: W. B. Yeats, with his romantic obsessions and monkey-gland injections, raged against the loss of virility. Tóibín never labors his book’s point about the excesses of masculinity, preferring to focus on telling details and their analogues in his subjects’ work. Through them, he makes Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know an engaging study of influence, ambition, love—and their discontents.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction is published by New York Review Books. He is working on a novel and a book about sentences.