Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Anomie, brutality, pop culture, the art world: what makes autofiction autofiction these days?

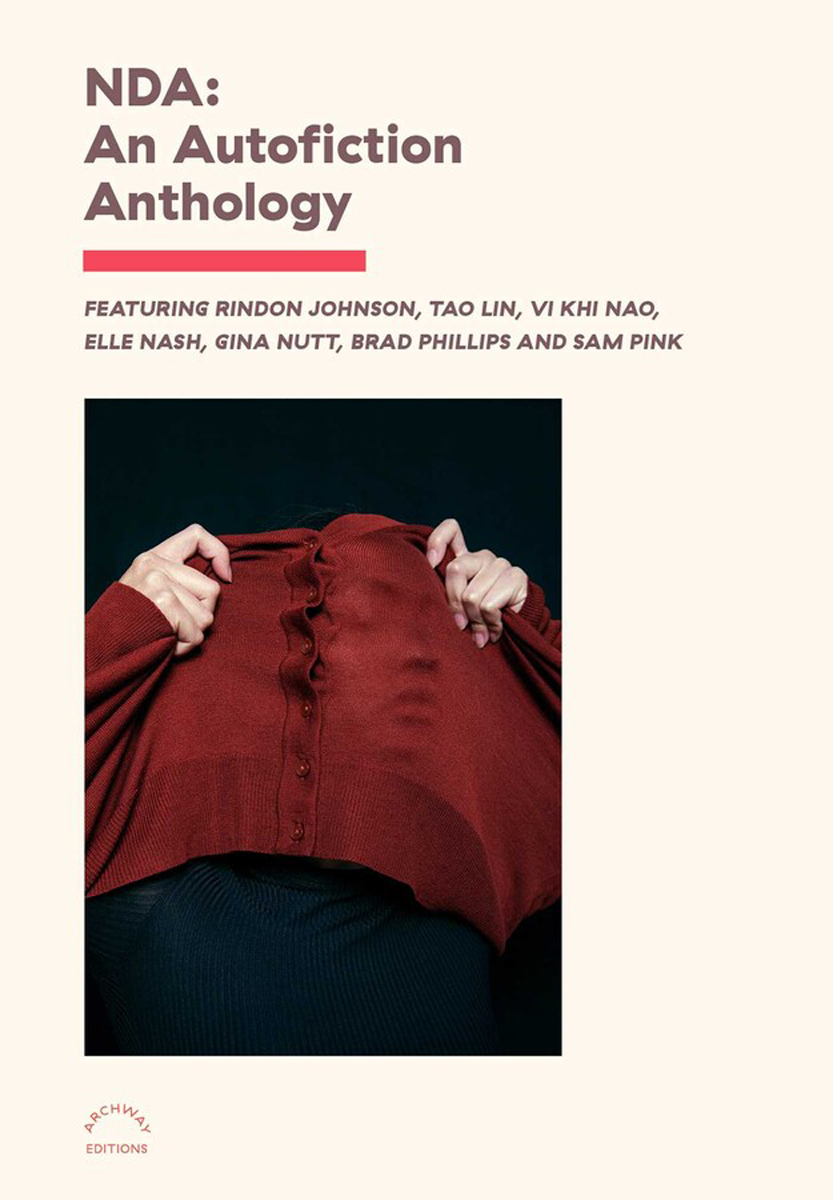

NDA: An Autofiction Anthology, edited by Caitlin Forst, Archway Editions, 204 pages, $15.95

• • •

In her laconic editor’s note to this faintly baffling collection of short fiction by fourteen writers based mostly in the US, Caitlin Forst says: “Autofiction has recently been hit with moral, academic, and critical scrutiny. I am not moral, academic, or a critic.” Nice disclaimer, begging all the questions. But first one wants to ask—recently? It’s an odd assertion about a genre (likely not the word) that has dominated anglophone literary chat for a decade or so, and a form (still not the word) lately acknowledged by the award of a Nobel Prize to Annie Ernaux, who’s been writing autofiction, if such exists, for half a century. Why this peculiar urgency on Forst’s part, and why her defensive tone? As if autofiction, or an idea of it, has not composed the mainstream of fiction for a while, and been a tributary for decades at least? There are only partial answers in NDA: An Autofiction Anthology.

Among the established and lesser-known writers here, little indicates that any actual auto might be at stake—a sense of self as predicament, more or less stable entity. Just saying I is not the same thing as setting this self in motion. Efforts to define autofiction have sometimes centered on what the critic Philippe Lejeune called le pacte autobiographique, a relation of readerly trust that depends on a book’s narrator having the same name as appears on the title page. An inadequate criterion when it comes to fiction, even very life-adjacent fiction. Another possible definition: autofiction is a descendant of the coming-of-age bildungsroman, or its more reflexive cousin, the Künstlerroman: here the narrator is not merely an artist or writer, but the only one capable of crafting the very text you’re reading. A perennially appealing, self-reflecting ruse for the creative writing student, but one that hardly exhausts the range of writers now routinely corralled inside the catchall of autofiction.

Possibly the term simply names what we do these days, however we do it, and has gotten so generalized that it may not matter, for example, if the opening story in this anthology has a basis in its author’s experience. Vi Khi Nao’s “Field Notes On Suicide Or The Inability To Commit Suicide Or It’s Hard To Follow A Pomeranian Around” occupies a zone somewhere between short story and prose poem, its barely-there protagonist sketching the ragged precincts of an unnamed city: “The lonesomeness of her existence makes the desolate landscape before her ache with desiccated, nocturnal residuum.” Starbucks, suicide, recollections of the Iran-Iraq War, the deathly presence of an American imperium: all of this is so much texture without much in the way of narrative, persona, sustained voice or tone. A good deal of work in the collection proceeds in this fashion: litanies of anomic encounters, fragments of aging pop culture, hints or sometimes eruptions of violence.

There are certainly stories (or are they instead pieces?) in NDA that fit the rubric of the Künstlerroman—that is, if we stretch the definition to describe a type of fiction or essay that exists on the periphery of an actual or imagined art world. Some of the characters in these autofictions are artists, or hang out with artists, or at least happen to be en route to art openings when things start going wrong for them. Artist and poet Rindon Johnson, in “Excerpt from And If I Could, I Truly Would,” a fragmentary text ventilated by a lot of white space: “Recently with my sculptures I have been making dyes to make them brown, black, blue, like me.” Johnson’s story also made me wonder: How many fleeting references to Ana Mendieta can we bear before the habit starts to seem an erasure of that artist’s life and work? But time and again the larger, artistic question seems to be: How can fiction, or this version of it we are calling autofiction, approach the condition of contemporary American TV, or a subpar Netflix movie?

The better and (perhaps coincidentally) longer stories in NDA tend to an oddly labored or incidental narrative design. In Tao Lin’s “Canadian Gay Porn Site,” the author/narrator recounts his being approached by someone from said site in search of “hot, brainy boys.” (This in 2009: “I was very active on the internet back then, doing things which detractors called ‘gimmicks.’ ”) The most substantial piece here, David Fishkind’s “The House on the Hill in the Country,” relays at a self-consciously somnolent pace the near-adventure of a young couple hoping for an idyllic rural rental—Fishkind writes as if aping the hokey longueurs of a series like The Watcher. An idea of narrative premise as mere setup, anecdote, or bit seems to animate such a story. Elsewhere it really doesn’t work: in “The Roman Soldier,” horror novelist B. R. Yeager concocts a scene of sexualized bullying or hazing that swiftly turns to cartoon gore—as with several of the weaker stories here, the final-sentence payoff is sheer amateur stuff.

Which may also be a reason NDA exists as a collection (hardly an anthology): to argue for a decidedly unliterary, determinedly unpolished kind of autofiction. Nobody is going to confuse this kind of thing with Rachel Cusk. The sense of a slightly forced desultoriness is also one way to read Forst’s editorial reticence: her seeming lack of interest—that was all of her editor’s note, above—in claiming any coherence among the writers. If NDA was the pilot issue of a tiny-circulation journal, you might say: Look forward to issue two, and what’s with the “autofiction” thing? As a book, it makes no sense. Instead, it floats an idea of autofiction as simply the mode in which prose is now written, a mode in which the self being described, rather than examined, is made up of ancient motifs from American culture (spacey road trips, sudden brutality), flecks of domestic or online life, sad bouts of attempted lyricism.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination will be published by New York Review Books in spring 2023. He is working on a book about Kate Bush’s 1985 album Hounds of Love.