Nicholas Elliott

Nicholas Elliott

From Christ and carpet bombings to Jean Seberg and madness: a retrospective of the French post-New Wave filmmaker.

Elie (Anne Wiazemsky) in L’enfant secret. Image courtesy The Film Desk.

“Philippe Garrel: Part 1,” Metrograph, 7 Ludlow Street, New York City, October 12–26, 2017

• • •

In 1979, thirty-one-year-old French filmmaker Philippe Garrel, fifteen years and more than a dozen films into a precocious career, did something he had never done before: he made a movie with a screenplay and a linear story. One thing that hadn’t changed was that Garrel had no money. Shot in fourteen days on black-and-white 35mm film, his feature lingered in the lab for three years, waiting for bills to be paid. When it was finally released in 1983, L’enfant secret was hailed by discerning critics as not only a great film, but also a return to the land of the living by a young artist who had once embodied the zeitgeist of the tumultuous late 1960s, a filmmaker so keenly attuned to his generation’s psychic state that Jean-Luc Godard had reportedly responded to one of his films by announcing he himself could now stop making movies.

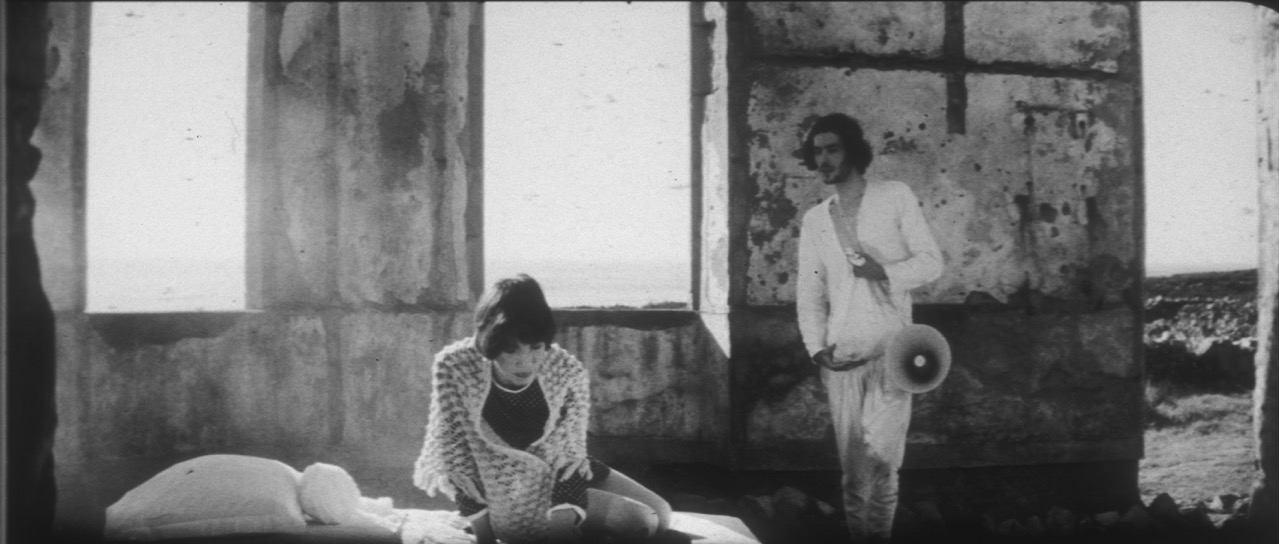

Marie (Zouzou) and Jesus (Pierre Clementi) in Le lit de la vierge. Image courtesy The Film Desk.

This October, the Metrograph in New York will present L’enfant secret’s long overdue first US theatrical run, following the first part of a Garrel retrospective opening the twelfth. This generous sampling of a half-century career, including all the films discussed below, should build on the appreciative but limited American reception of Garrel’s most recent films to finally establish him here as the towering post-New Wave filmmaker that he is recognized as in France. Viewers will see that what distinguished Garrel in the heady times culminating in the student revolts of May 1968—aside from the fact that he had started making films professionally at an age when some of his contemporaries were still coming to terms with long division—was a freewheeling but formally rigorous approach that fused contemporary anxieties with timeless allegory, paying equal attention to his generation’s exuberance and its alienation. In Le lit de la vierge (The Virgin’s Bed, 1969), a gaunt, reluctant Christ wanders the desert with a megaphone in a series of disjointed, increasingly hallucinatory scenes set to the howl of carpet bombings. In this Cold War nativity and films like La cicatrice intérieure (The Inner Scar, 1972), Garrel achieved something seldom seen before or since: a kind of shoestring experimental super-production shot on stark terrain in Iceland or Morocco, a form of psychedelic ritual allying visionary spectacle and inner turmoil. Bad trips have never been so ravishing.

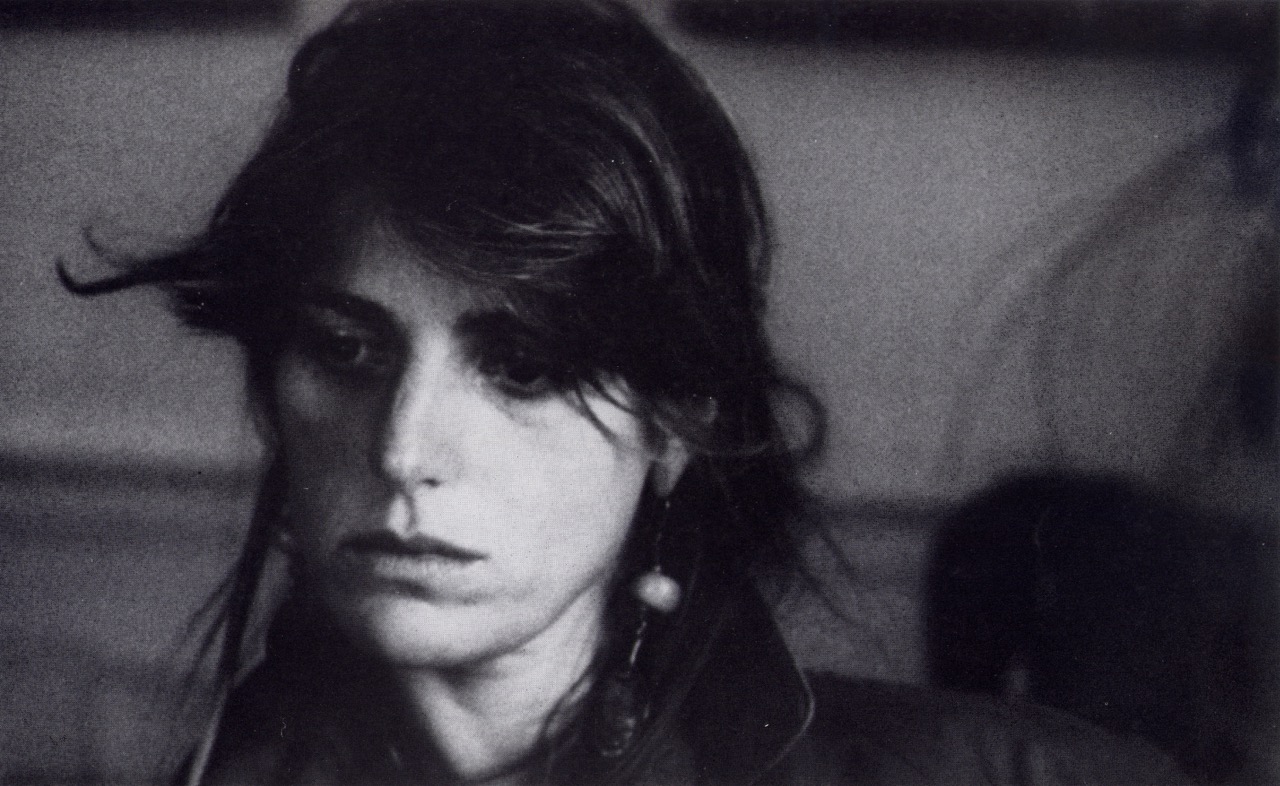

The Woman (Nico) in La cicatrice intérieure. Image courtesy The Film Desk.

While Garrel continued to make films throughout the 1970s, he went further and further in pursuit of what many now see as cinema in its most distilled form, but was then dismissed as hermeticism. Imagine if all the agonizing beauty and emotional intensity we associate with Dreyer, Bergman, and Cassavetes were encapsulated in a woman’s face: the haunting portrait film Les hautes solitudes (The High Solitudes, 1974), a succession of silent black-and-white close-ups of Jean Seberg walking the thin line between Method acting and actual madness, does nothing less and probably much more. Yet by the end of this era, what ebullience was left in Garrel’s work was all in the wintry beauty of his formal command: Le berceau de cristal (The Crystal Cradle, 1976) finds Garrel rivaling his master Georges de La Tour in the art of portraiture but ends in wordless suicide.

Jean-Baptiste (Henri de Maublanc) and Elie (Anne Wiazemsky) in L’enfant secret. Image courtesy The Film Desk.

Coming neatly on the tail of that long, hard decade, L’enfant secret reads like a weather-beaten, time-worn report by a man who has struggled back from a distant place: from the solitude of an artist blind to commerce, and the drug abuse and shock therapy born of the disappointments of a generation that had hoped mightily. Its story is a thinly veiled rendition of Garrel’s relationship with the German chanteuse Nico, the mother of a “secret child” (the enfant secret of the title, left untranslated for US release), fathered but unrecognized to this day by Alain Delon. After being Garrel’s muse and occasional star throughout the 1970s, Nico served as the inspiration for many of his subsequent films, all of which flirt with autobiography but make strikingly different use of the same well of material. Elle a passé tant d’heures sous les sunlights . . . (She Spent So Many Hours Under the Sun Lamps, 1985) is Garrel’s most tactile work, a dizzying film-within-the-film tale in which jump cuts and flashes of light evoke cinema’s grip on life, while J’entends plus la guitare (I Don’t Hear the Guitar Anymore, 1991), Garrel’s first film after Nico’s untimely death and the best entry point to his work, eschews any reference to the couple’s film collaborations to tell a modest but arresting love story, from a first encounter in Positano to a visit to Nico’s grave in Berlin. This rare film in color by a master of richly textured black and white perfects Garrel’s art of the ellipsis: there is an invigorating abruptness in the way years go by unannounced between two shots, then something marvelously gentle in the camera dwelling on the dawn of emotion on a man’s face. In Sauvage innocence (Wild Innocence, 2001), Nico’s story is again the subject of a film within the film, but is framed by Garrel’s version of a classical tragedy: a director agrees to smuggle drugs to finance the anti-drug film in which he has cast his girlfriend, only to find this Faustian pact endangers their relationship.

Jeanne (Brigitte Sy) in Les baisers de secours. Image courtesy The Film Desk.

Romantic love and the possibility of family are the thematic backbones of Garrel’s work, from his earliest agnostic takes on Christian tradition, like his free-associating first feature Marie pour mémoire (Marie for Memory, 1967), in which two teenagers called Jesus and Mary want to have a child together but are separated by a dystopian society that looks a lot like late-1960s France, through later “narrative” films like Les baisers de secours (Emergency Kisses, 1989), in which Garrel takes one of his few acting turns as a film director who estranges his wife, a theater actress, by casting a movie star to play her in a film about their relationship. Les baisers de secours features Brigitte Sy, Garrel’s wife at the time, his parchment-faced father Maurice, and his five-year-old son Louis, later a star in his own right, all more or less playing themselves. In the hands of a director who trafficked in naturalism or psychology, the film might have been a monument of immodesty, but Garrel’s sole interest, here and elsewhere, is in presence, in watching the surface of faces and the space between bodies as people feel and think. His gift to us, even in those early films recasting adolescent anguish as widescreen myth, is intimacy. While Garrel’s predecessors in the French New Wave were acclaimed for taking the cinema into the streets, he and the directors of his generation, notably his friends Chantal Akerman and Jean Eustache, may be remembered for retreating to hotel rooms and rented apartments. As every one of his films reminds us, nothing is lost in allowing us closer.

Nicholas Elliott is a writer and translator living in Queens. He is the New York correspondent for Cahiers du Cinéma and a contributing editor for film for BOMB. His short film Icarus was screened at New Directors New Films in 2015.