Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

The peculiar pop power of the late artist’s work.

Joyce Pensato, Shout, 2007. Charcoal and pastel on paper, 60 × 87 1/2 inches. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel.

Joyce Pensato: Batman vs. Spiderman, Petzel Gallery, 35 East Sixty-Seventh Street, New York City, through March 20, 2021

Joyce Pensato: Fuggetabout It (Redux), Petzel Gallery, 456 West Eighteenth Street, New York City, through March 6, 2021

• • •

Joyce Pensato’s shtick never got old. Her brash renderings of cartoon characters, from Batman to Homer Simpson, in the gestural tradition of AbExers such as Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning, were generative, surprising, never rote. And by shtick I don’t mean to say that the painter’s practice was gimmicky, only that it was comic, in a twisted way; and that it had some of the qualities of an act, one she sustained for decades. (She referred to her longtime Brooklyn studio as Joyceland and liked to pose, even lip-synch, with her paintings.) Pensato fixed on her pop subject matter early, and gradually revealed, as if layer by layer, the talismanic power and malevolent potential she detected in her culturally ubiquitous masked or bug-eyed icons, her painting gaining speed, it seemed, up until the year she died, in 2019, at age seventy-seven.

Two shows, organized in collaboration with Pensato’s estate, at Petzel Gallery’s Upper East Side and Chelsea locations, feature focused selections spanning more than forty years of her output. Nothing so comprehensive as a retrospective, the exhibitions instead bookend her career, showing the artist wrestling with the germ of her defining idea in a suite of charcoal drawings from the mid-seventies (small in scale relative to what was to come), and then that idea’s spectacular fruition, in a reprise of a monstrously great installation from 2012, alongside a generous number of her towering, wrathfully or gleefully exuberant works, also from her last, productive decade.

The early works, on view uptown in Batman vs. Spiderman, date from Pensato’s time at the fabled New York Studio School, whose pedagogical approach—during the ascendance of Pop, Minimalism, and Conceptual art—somewhat anachronistically emphasized atelier-style hands-on instruction with working artists and back-to-basics skills, such as life drawing in the tradition of Cézanne and Giacometti. (With Mercedes Matter at its helm, the institution was founded in 1964, and its accompanying manifesto signed by such luminaries as Mark Rothko, Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, and de Kooning himself.) Pensato has said of the formative time that she was “resisting working with the traditional still life—apples and pears and all that crap.” She hit upon a winning strategy when she pulled a life-size cardboard cutout of Batman off the street, positioning the figure with other objects and characters.

Joyce Pensato: Batman vs. Spiderman, installation view. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel. Photo: Thomas Mueller. Pictured: all works untitled, circa 1976.

A dynamically confusing untitled composition from 1976—articulated in bristly and smudgy charcoal grisaille on a big piece of paper, around three by four feet—captures the superhero falling backward, caught on the arm of a contorted doll on horseback as another toy walks stiffly out of the frame. Or perhaps all of the figures are in a heap, and the viewer’s perspective is that of someone looking down at them on the floor. Other drawings, in the same format and from the same year, make clear that the masked Bruce Wayne was Pensato’s springboard into rich terrain: Spiderman appears more often, in dramatic stances, returning our gaze. (It looks as though Pensato was working from action figures, with their segmented, semi-dexterous severity.) In a characteristically spatially weird work from the group, a chair floats up in front of the Marvel star. A cropped Superman is crouched with, or stuck to, a stuffed Mickey Mouse in another picture; the two characters form what looks like, at first glance, a boulder or a crushed-car John Chamberlain sculpture, with eyes.

Joyce Pensato: Fuggetabout It (Redux), installation view. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel. Photo: Thomas Mueller. Pictured, left to right: Underground Homer, 2019; Daisy, 2012; SmackDown! Lisa, 2018.

Such “still life” compositions—in which her stylized, merchandized elements were brought into a compositional relationship in a bouquet or bowl-of-fruit tradition (sort of)—gave way by the early nineties to a distinct style of portraiture. She favored frontal, symmetrical views smack in the middle of the page; and Disney’s mascot became a solo star in her world (along with Donald Duck, Felix the Cat, Elmo, and more). In the Chelsea exhibition, an enormous, smoky, pastel-tinted charcoal rendering of a diabolical Lisa Simpson, from 2018, and a nervous Homer, from the next year, on the opposite wall attest to Pensato’s enduring interest in athletically expressive drawing; her slashing marks and abraded, effaced surfaces give even smiles an air of ominous portent. The knockout show as a whole demonstrates her singular practice of controlled chaos across media, bent on revealing the appeal and toxicity of Americana—from masculinist myths of action painting to the malignant subtext of cartoon physiognomy.

Joyce Pensato: Fuggetabout It (Redux), installation view. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel. Photo: Thomas Mueller. Pictured, left to right: Who Killed Kenny?, 2012; What’s Next, 2015; Eyes Wide Open, 2016.

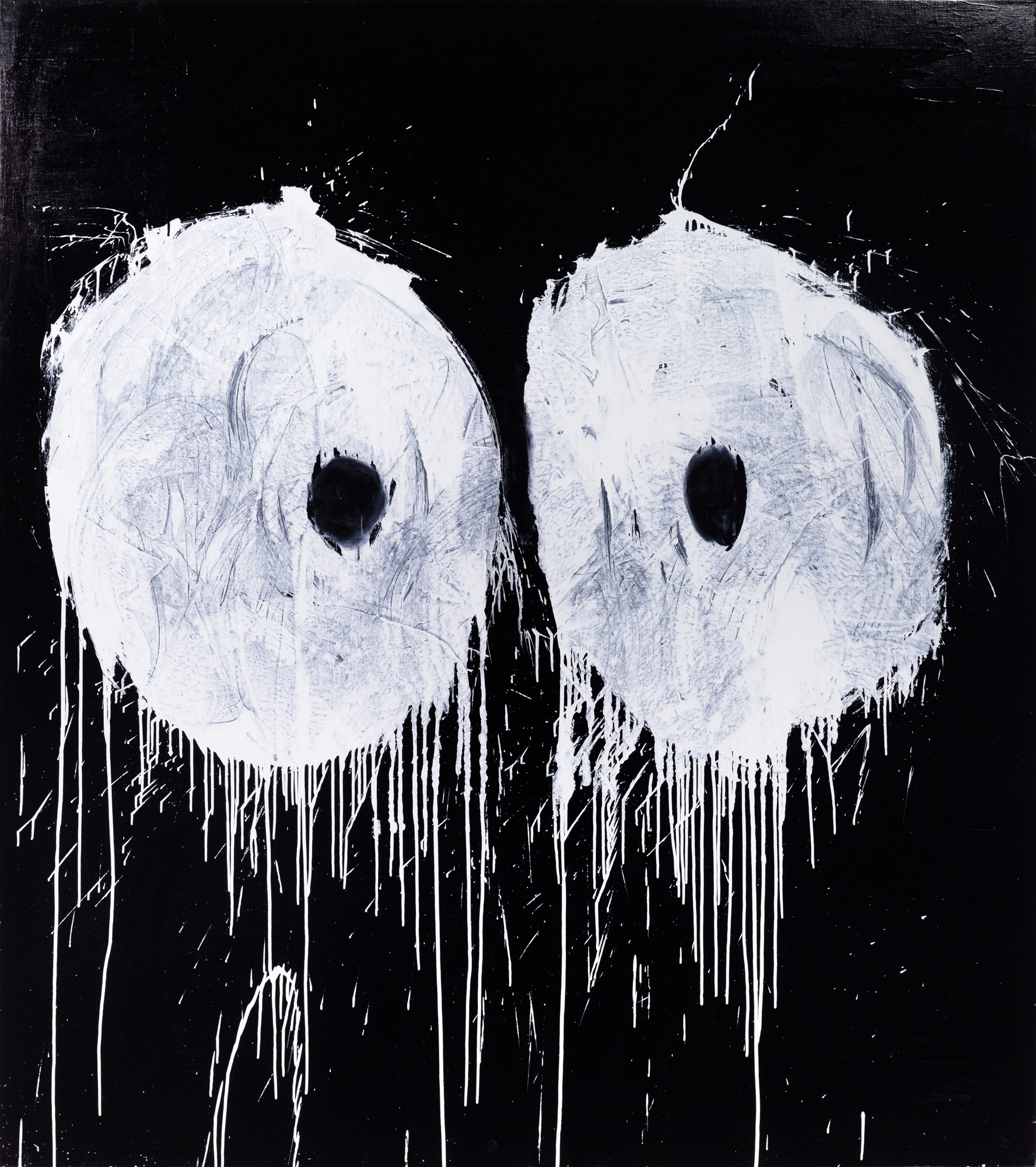

A stunning, unsettling group of her “eyeball” paintings, including the five-part work What’s Next (2015), prove that her addition of hardware-store enamel paint (a development she dates to 1989 or so) continued to produce breathtaking effects. In the stretch of grand canvases, the disembodied, but unmistakable, close-set white orbs that animate her cast of characters float in black fields. White paint drizzles from the goofy/scary doughnut forms in these stark statements, which look effortless, banged out. Jackson Pollock’s splattered expanses and Pat Steir’s rivulet curtains appear as representational techniques for graphic, branded imagery, stripped down to its expressive essence.

Joyce Pensato, The Look Out, 2016. Enamel on linen, 72 × 64 inches. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel.

When I first saw these eyeballs (or similar ones) some years ago, I was reminded of Ellen Gallagher’s work from the nineties. In what look like pale modernist grids from afar, the Black painter articulated tiny, isolated features, such as mouths and googly eyes, drawn from minstrelsy’s codes of caricature, repeating them, ad infinitum, like strings of pictographic code. Her decontextualization of the culturally embedded symbols could not abstract them beyond recognition. Likewise, with an opposite distortion of scale, Pensato’s lexicon of eyes—which broadcast comic naïveté and buffoonery as well as fear and surprise—seem to illuminate through isolation. The indebtedness of Disney and Looney Tunes et al. to longstanding racist comedic conventions, despite attempts to render them race-neutral and benign, is palpable here as an element of these distilled images’ quality of threat.

Joyce Pensato: Fuggetabout It (Redux), installation view. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel. Photo: Thomas Mueller. Pictured: Fuggetabout It (Redux), 2021 (detail).

Pensato’s sprawling installation work Fuggetabout It (Redux), for which the Chelsea show is titled, sets the stage for all else on view. In 2012, when the artist was forced out of Joyceland, she transported its alarming, edifying contents to Petzel’s former space on Twenty-Second Street for an acclaimed deluge of a show, which felt part landfill, part crime scene. Here, her former studio’s islands of detritus and inspiration are deftly reconfigured once again. Scores of paint cans join legions of enamel-spattered photos and toys; artifacts of racist kitsch surface occasionally, neither hidden nor highlighted, presented honestly as part of American mass media’s churning guts.

Joyce Pensato: Fuggetabout It (Redux), installation view. Courtesy Joyce Pensato Estate and Petzel. Photo: Thomas Mueller. Pictured: Fuggetabout It (Redux), 2021 (detail).

A Big Bird booster seat, stuffed South Park characters, a filthy plush Sylvester the Cat, and countless versions of Mickey and Donald offer a vision of Pensato’s process as one of slow metabolization, the production of messy composites rather than copies—even if the brushwork itself looks deliriously fast. Pulling back the curtain on her studio was a genius gesture, I think, and it’s exhilarating to see it again. The astounding accumulation of treasure and garbage, which luckily supplanted apples and pears, is a revelation when placed next to her still-vital, elegant late paintings.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.