Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

In an exhibit mixing the artist’s paintings with old master works, a delightful liberation from sense and pretension.

Karen Kilimnik: The Kingdom of the Renaissance, installation view. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. Pictured, center left, above mantle: Karen Kilimnik, Barbados, 1999. Far right: Karen Kilimnik, dinner in the alley, 2010.

Karen Kilimnik: The Kingdom of the Renaissance, curated by Mireille Mosler, Sprüth Magers, 22 East Eightieth Street, Second Floor, New York City, through March 18, 2023

• • •

“While no one is making masterpieces anymore, no one is trying to make them either,” wrote Rhonda Lieberman in Artforum in 1992. Titled “The Loser Thing,” her piece was a finger-on-the-pulse exegesis of that ’90s art phenomenon, when Gen X, Grunge-era, so-called slacker aesthetics informed a few varieties of shoddy object-making and self-abasing performance work. Lieberman mentioned the painter and installation artist Karen Kilimnik only in passing here (focusing mostly on those adopting abject themes and clownish confessional modes instead), but she nailed Kilimnik’s thing—her poker-faced air of transgressive underachievement—a few years later, in 1994. Lieberman (again in Artforum) describes her fan-art-ish renderings of girlish imagery, sourced from fashion magazines, tabloids, and old master paintings, as a “zombielike presentation of the froufrou,” and identifies Kilimnik’s critical, conceptual pose: “By taking glamour particles at face value and reproducing them in their psychotic disconnectedness,” she is, in Warhol’s tradition of canny vacancy and celebrity worship, “an incorrect consumer.”

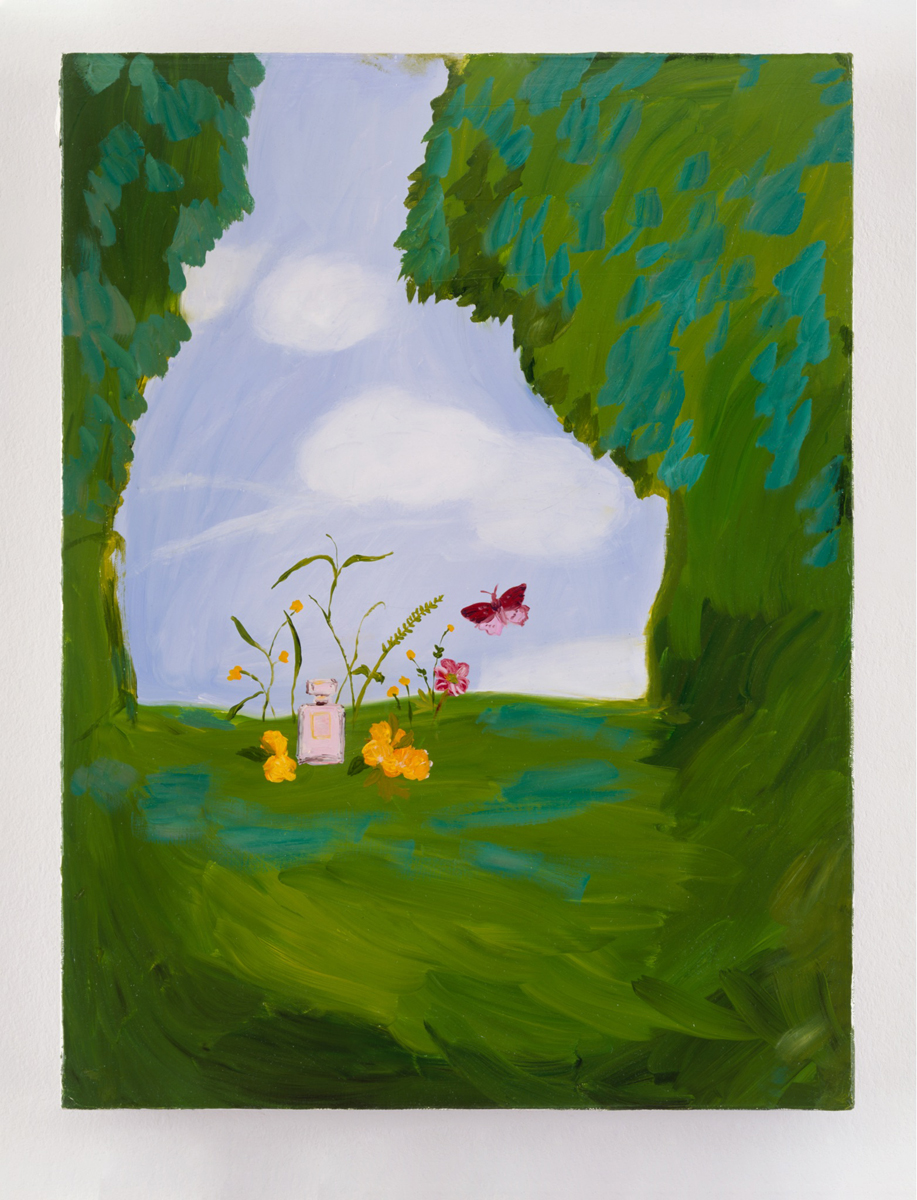

Karen Kilimnik, the happy weeds + insects in the field on a summer day, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, and Sprüth Magers.

The painter has, over the years, incorrectly consumed—absorbed and awkwardly or incoherently reflected back—some of the art on view in the exhibition The Kingdom of the Renaissance at Sprüth Magers. Curated by Mireille Mosler, a New York art advisor and dealer who specializes in European, especially Dutch, Renaissance art, it is a mélange of Kilimnik’s paintings (with a focus on her animal imagery), spanning the 1980s to recent years, and wares, selected by Mosler, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The relationship between the old objects and Kilimnik’s fucked-up renditions of them, or their motifs and genres, is not one-to-one or precise (her desultory invocation of a vague art-historical and aristocratic past is more of a vibe), except in one remarkable instance—an image of the painter’s, dinner in the alley (2010), appears with its source.

Karen Kilimnik: The Kingdom of the Renaissance, installation view. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. Pictured, left to right: Jan Baptist Weenix, A Boar Hound with a Joint of Meat Near an Enraged Cat, ca. 1650–55. Karen Kilimnik, the witche’s familiars in the woods, 2010. Jan Fyt, A horse, an ox, dogs, a boar, stags, a goat and foxes, ca. 1640s. Karen Kilimnik, friends in the woods, 2010.

The small canvas is not fucked up—for this one, I take that back. While much of Kilimnik’s early work leveraged a stilted kind of teenaged copying, her repertoire came to include different registers of anti-virtuosity, such as a lyrical hobbyism that’s more than proficient. For dinner she takes a messy Impressionist approach to a pre-modern subject: a voluptuously fraught scene of hunger, fear, and intimidation by the Dutch Golden Age painter Jan Baptist Weenix. A Boar Hound with a Joint of Meat Near an Enraged Cat (ca. 1650–55) depicts a seductive drama unfolding in the shadows, grand in scale but not in theme. The canine protagonist slings a front leg over the dismembered haunch of its meal protectively, affectionately, as though in alliance with the meat against the nefarious crouching cat whom it swivels its neck to lock eyes with. Kilimnik fixes upon the concentrated pathos in the hound’s face, the almost comic weariness and fear with which it regards its little tormentor, as well as the grace of its sloping paw. She captures both elements with speed and efficiency in her brighter, gestural, less grotesque, and extremely scaled-down version of the tense situation.

Karen Kilimnik: The Kingdom of the Renaissance, installation view. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. Pictured, left: Karen Kilimnik, cats playing in the snow, Siberia, 2020. Right: Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, An odd-eyed cat, 1894.

Elsewhere, unexplicit, associative, and abstract links between historical and contemporary works are exciting or entertaining, too. Kilimnik’s extra-insouciant, blithely disastrous underwater scene, Barbados (1999), in which spiny seahorses are drawn in raised lines of glitter over a dingy lavender ground, is humorously paired with a sixteenth-century bronze inkwell taking the form of a ridged and scaled sea monster, from the workshop of Italian sculptor Severo da Ravenna. The blue-cast picture cats playing in the snow, Siberia (2020)—which you can find reproduced on an Acne Studios T-shirt, jacket, and shopping bag—features two fluffily articulated friends holding a ribbon in their mouths, recalling a Hallmark strain of kitsch. It’s paired with the exhibition’s stunning best-in-show, An odd-eyed cat (1894), by Dutch-Belgian Romantic painter Henriëtte Ronner-Knip. The portrait, a bust in which the feline subject—with one blue and one green eye—meets the viewer’s gaze, has an acidic radiance and a thrilling confrontational edge.

Karen Kilimnik, friends in the woods, 2010. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, and Sprüth Magers.

There are other fine moments, demonstrating Kilimnik’s roving interest in the artistic preoccupations of previous centuries. Two related, very beautiful works of hers, from 2010, both portraying a group of seven or eight dogs of various breeds gathered in the night, flank the murky A horse, an ox, dogs, a boar, stags, a goat and foxes (ca. 1640s), a compositionally similar convening of beasts by Flemish animalier Jan Fyt. Vignettes by the English satirist Thomas Rowlandson, capturing debauched nobility at gaming tables, from 1787, are hung cleverly near some of Kilimnik’s earliest drawings on view, including the pastel-on-paper Card games — Neptune’s grotto ancient Greece and 1745 (1985), which features fragmented imagery: playing cards, a Louis XV chair and an aristocratic lady, rather like one of Rowlandson’s, spraying azure puke.

Karen Kilimnik: The Kingdom of the Renaissance, installation view. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. Pictured, left: Thomas Rowlandson, A gaming table at Devonshire House, London: Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, Harriet, Lady Duncannon, the Prince of Wales and others gambling, 1787. Center: Karen Kilimnik, Card games — Neptune's grotto ancient Greece and 1745, 1985.

The press release for The Kingdom of the Renaissance is alert to the danger that the focused nature of Mosler’s selections might mislead, might give the impression that the painter, in her references to the previous centuries, “pays abject homage” to old master inspirations. Rather, it clarifies, these are examples, details plucked from her cumulative practice of world-building. Kilimnik’s cosmology is not constructed in service of narrative or tribute; it’s a fantasy realm where nothing much ever takes place. Sharing with the Disney-princess universe an interest in hazy composites, continental royalty, animals, and Rococo, hers differs in its haphazard handcrafted quality, and because it’s unburdened with the pretense of making sense. In the context of her practice—a body of work like a mood board writ large—a painting by Jan Baptist Weenix is, per Lieberman, a glamour particle, just like a picture, for example, found in Russian Vogue of Kate Moss. (The model was a frequent subject of the artist’s in the ’90s.)

Karen Kilimnik: The Kingdom of the Renaissance, installation view. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

No claim is made that the old master works on view alongside Kilimnik’s are masterpieces (and in the presence of her paintings, the term old master sounds all the more regressive and absurd). The historical objects function as precious stuff, made for luxuriant settings of landowning wealth; they represent fantasy and aspiration, and a time when artists tried, without irony, to be Great.

Karen Kilimnik, cats playing in the snow, Siberia, 2020. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, and Sprüth Magers.

The irony is that Kilimnik, for her paintings and drawings here, ostensibly looked at reproductions (from magazines, books, auction catalogs, the internet), and her un-masterful interpretations of these images are now exhibited alongside—and in some cases priced higher than—real items like those they reference. While interesting to see how it’s played out over decades, the essential contradiction of the Loser Thing is not news—the trend’s existence, its ascendance, has always meant that the loser wins. That’s not the point, though, of this delightful, full-of-surprises, tonally brilliant animal-painting show. Commercial considerations aside, the point is to be—and I think this is enough—psychotically disconnected, froufrou, and fun.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and musician. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. Her band, Le Tigre, has reunited after seventeen years to tour in 2023.