Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Early-career paintings reveal the artist’s psychic mise-en-scène

already in place.

Louise Bourgeois, Fallen Woman (Femme Maison), 1946–47. Oil on linen, 14 × 36 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke. © The Easton Foundation.

Louise Bourgeois: Paintings, curated by Clare Davies, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City,

through August 7, 2022

• • •

It’s easy to forget that Louise Bourgeois was not always a giant. When I hear the artist’s name, I think of works like Maman—a thirty-foot-tall steel and bronze-cast spider who carries marble eggs in her wire mesh sac. That sculpture is from 1999, though; Bourgeois was in her late eighties when the towering arachnid-mother took form. And she was not yet thirty when she produced the first of the gloomy modernist oddities, with their haunted architecture and unlovely brushstrokes, in Paintings.

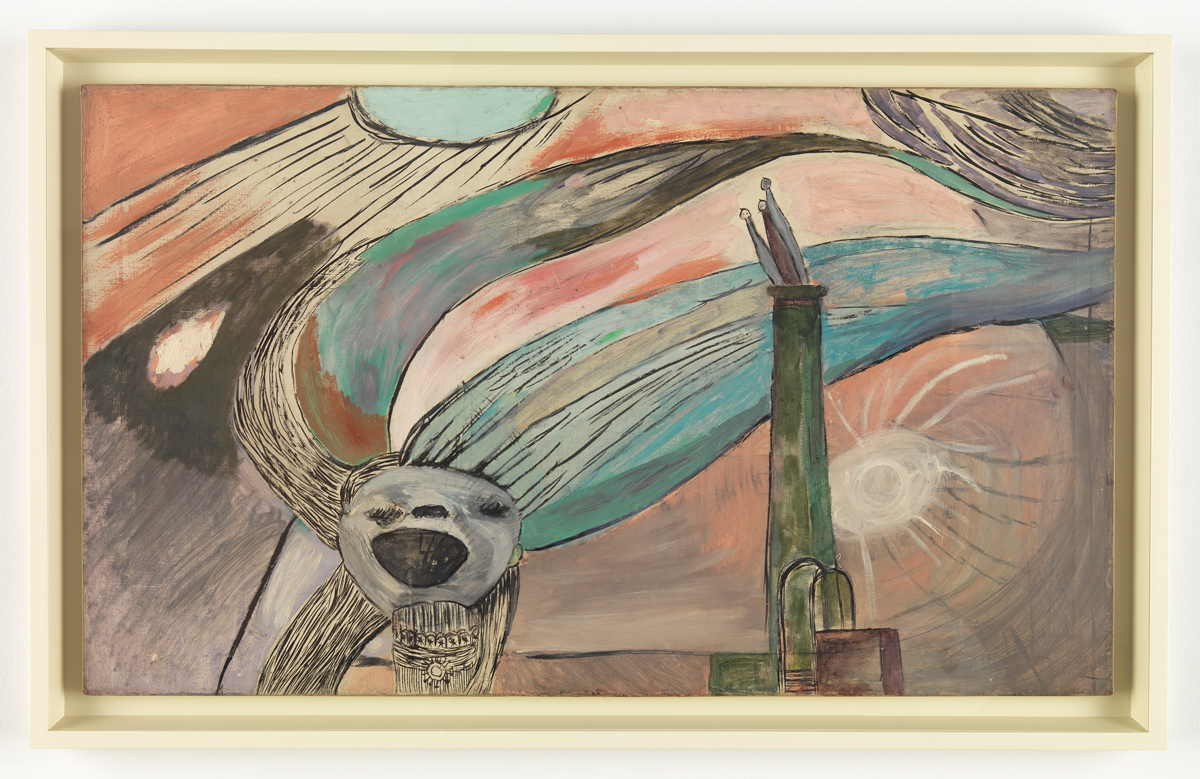

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1946–47. Oil on canvas, 26 × 44 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke. © The Easton Foundation.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s edifying exhibition features dozens of the more than one hundred canvases that Bourgeois made early in her career, between 1938, the year she emigrated from Paris to New York, and 1949, when her turn to sculpture was mostly complete. The modestly sized works show a starting point for her long, halting emergence as a force, and conjure an image of her as a young woman experimenting within the limits of the easel. (Her first retrospective, at MoMA, opened in 1982. Her most ambitious sculptures, installations, and environments—and her own larger-than-life status—came after that.) Never presented as a group before, and many seldom seen at all, the paintings throw the scale and production values of her later work into relief, and present her famous index of symbols—which came to include cages and clustered phalli as well as spiders and eggs—in a disorderly, germinal state. Most striking, though, is the unchanged psychic mise-en-scène of her work. Bourgeois’s unfaltering visual representation of an interior world, suffocating and infinite, where memory’s distortions readily take root and reign unchallenged, was fully formed from the start, it seems, and needed only to be brought into focus. Or maybe it didn’t: the scratchy, murky pictures, often formed by scumbled layers and simply drawn imagery, absent of painterly guile, are great, in their way.

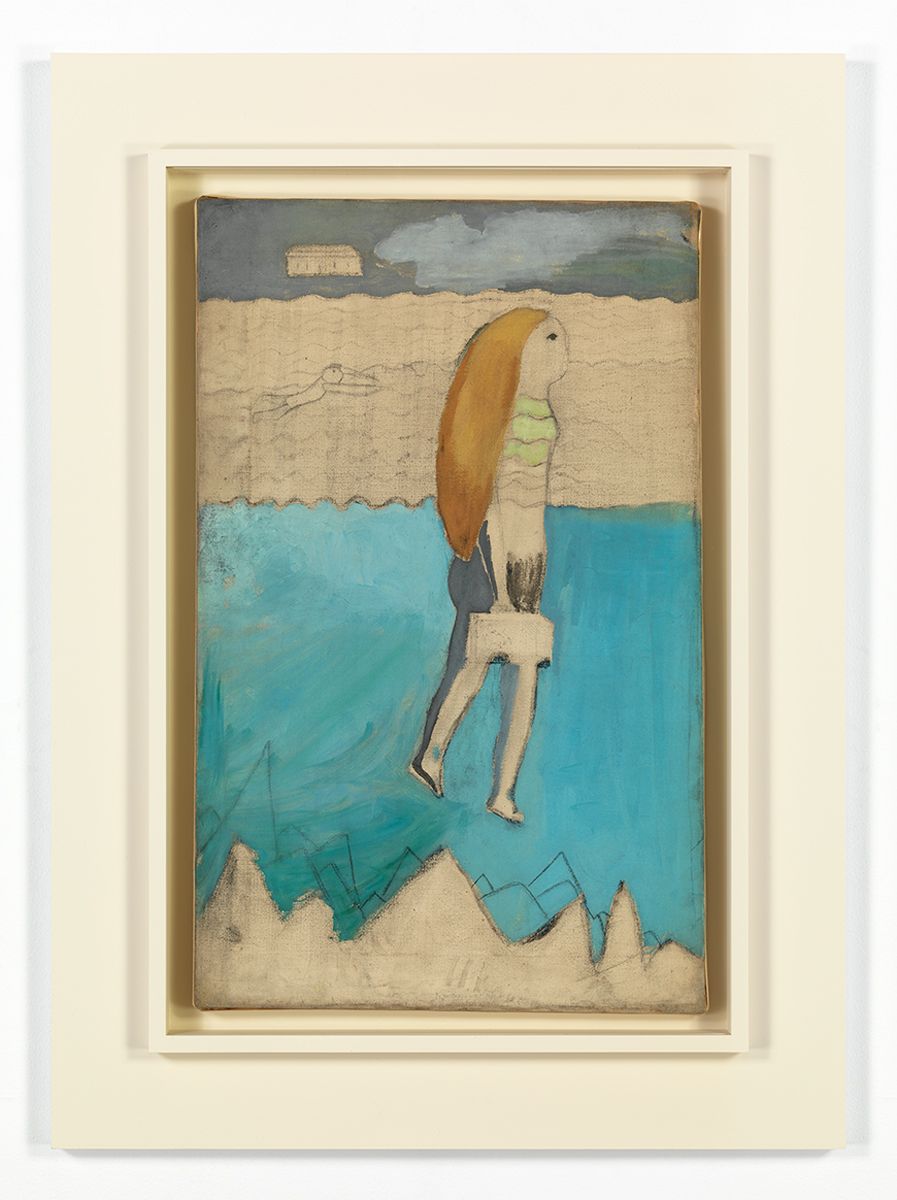

Louise Bourgeois, The Runaway Girl, ca. 1938. Oil, charcoal, and pencil on canvas, 24 × 15 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke. © The Easton Foundation.

A handful of self-portraits map the registers of her introspection as well as her untamed figurative range. The Runaway Girl (ca. 1938), which takes pride of place at the gallery entrance, is from just after she arrived in the US, newly wed to the American art historian Robert Goldwater. It offers perhaps the most straightforward narrative here, showing a simplified figure in profile, weighted with Bourgeois’s Rapunzel-length mane. She walks on a band of turquoise water, a tiny suitcase in hand, toward the foreground’s shoreline of fanglike rocks. Fast-forward to Self-Portrait (1947), and the tentative optimism of the young runaway is nowhere to be found. The artist’s head is a charred death star atop a ladylike outfit; she stands on a red floor and holds a flask—of poison, I think.

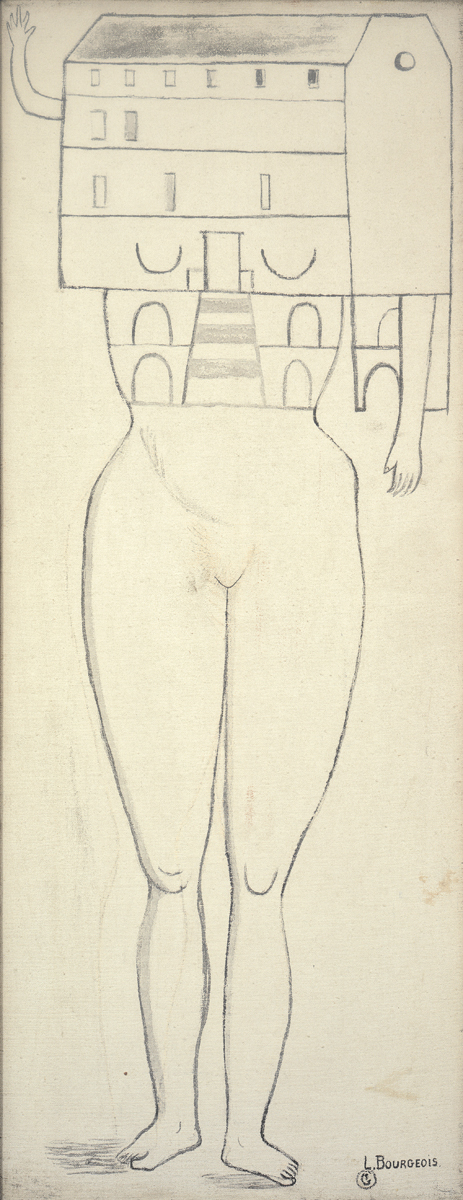

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Maison, 1946–47. Oil and ink on linen, 36 × 14 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke. © The Easton Foundation.

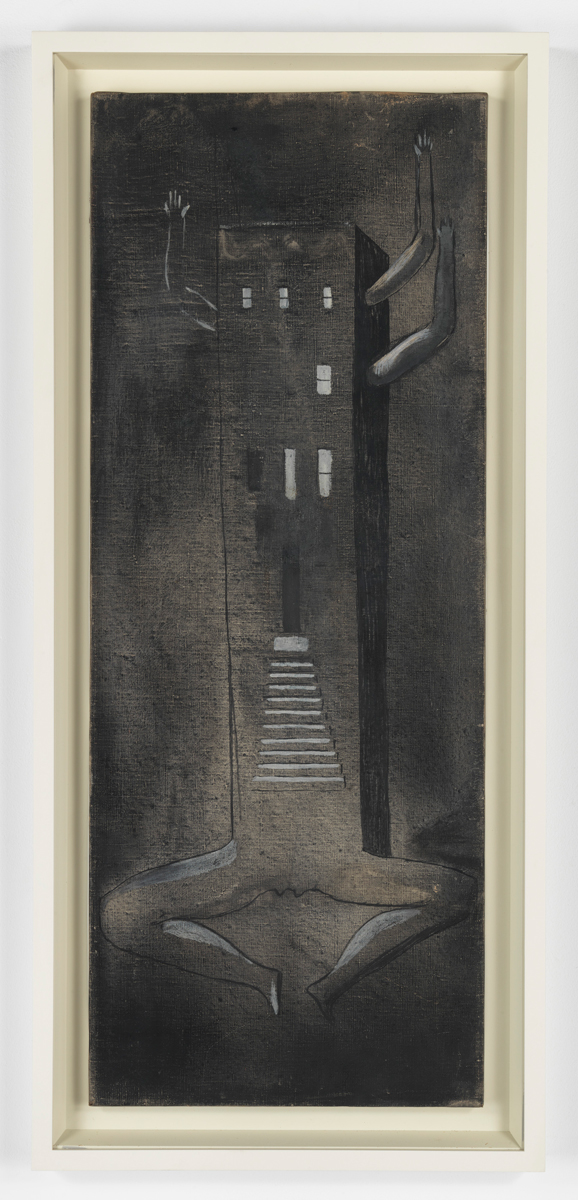

Her famous Femme Maison paintings, dated 1946–47, are also on view, three vertical compositions from the series installed in a row. Perhaps they’re not strictly self-portraits—they take aim at an institution, an archetypal mode of entrapment—but they critique a domestic role she played at the time (by now she had three young sons). The canvases were later seen as a precursor to works overtly concerned with gender and were cited by the feminist art movement. (Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s 1972 pedagogical experiment and collaborative installation work Womanhouse was named for Bourgeois’s woman-house hybrid images). The Femmes Maison appear related to a crisper, more graphic or diagrammatic Surrealism, as opposed to the shadowy hypnagogia of other, nearby paintings. Perhaps in rebuke of the André Breton–led boys club, from which she was excluded in Paris, the artist mimicked an exquisite-corpse structure with her anthropomorphic forms. Her dark monochrome version appeals to me the most—the “house” serving as an elongated female trunk looks like a walk-up apartment building, like mine. Bourgeois carefully silhouetted a pudendum and pair of spread legs at its base; three small arms toward the top sprout from its walls, raised as though in wailing distress, maybe surrender.

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Maison, 1946–47. Oil and ink on linen, 36 × 14 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke. © The Easton Foundation.

Individually, Bourgeois’s paintings can be wonderfully confusing in terms of pictorial space or in their suturing of divergent styles, both abstract and figurative. They are also fascinatingly diverse, arguably discordant, as a group. While in her last decades her sensibility came off as eruditely sui generis, in these pictures she more discernibly pays tribute to her influences, or she exorcizes her education. Many works evoke a looser Fernand Léger (a favorite teacher), the melancholy of a pre-Cubist Pablo Picasso, or the displaced statuary and desolate dream spaces of Giorgio de Chirico—such as in Bourgeois’s Regrettable Incident in the Louvre Palace (1947), with its exterior view and moonlit severity. Then there is the Symbolist anguish of Red Night (1945–47), in which a monstrous blue figure lies with three little faces (the artist and her sons) in a twin bed, adrift in gestural storm like a crimson Van Goghian sky, the scene’s dissociative, doorway point of view echoing Frida Kahlo. Art historian and catalog essayist Briony Fer names Pierre Bonnard a significant influence, presenting his 1939 painting Le placard rouge (The Red Cupboard) as evidence, which I would not have thought of, but yes: looking at the disorienting view of this moody container and its division of space, it does seem Bourgeois found in him a model for representing the experience of claustrophobia, a defining sensation in her art, its unifying atmosphere.

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled (double-sided), 1940 recto / 1990 verso. Recto: oil and pencil on board, verso: oil on board; 13 1/8 × 11 7/8 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke. © The Easton Foundation.

There is an underpinning, or maybe an undertow, of legend to contend with when considering the sculptor, as she came to be known despite the many paintings, prints, and drawings she made throughout her career. There is the story of her teenage talent for improvising missing passages of antique tapestries, drawing in the feet of figures worn out at the compositions’ bottom edges while at work in her family’s restoration atelier; the trauma of her father’s protracted domestic subterfuge, an affair with the children’s live-in English tutor, which lasted for around a decade; and the escalating drama of the artist’s long-morphing lexicon. While sometimes it feels a little wrong to me, possibly insidiously sexist, to see Bourgeois’s radical project as autobiography, she almost insisted on such a reading. She spoke often of her childhood as the enduring subject of her work, conceiving of her practice as one of self-discovery and decryption—and of coping—more than invention. Last year’s stunning and dense exhibition, Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter, at the Jewish Museum illuminated the artist’s deep study of and turbulent relationship to psychoanalysis, pairing her vivid written accounts of her treatment from 1952 to 1985 with parallel visual expressions of her insight—or of her passionate struggle for it.

Louise Bourgeois, Confrérie, ca. 1940. Casein on board, 32 × 44 inches. Photo: Scott Hess. © The Easton Foundation.

Paintings might be seen as a prequel, showing us a Bourgeois less conscious of her unconscious, her grasping reflected in palimpsest-like surfaces and psychological self-portraiture. Here, in the strange, voyeuristic views of architectural interiors as bloody, internal spaces, and building façades as bodies with limbs and orifices, there are hints of her epic scope. Such compositions seem forerunners to series such as her room-size Cells, which were, at the time she made the two-dimensional works here, decades away. The emergence of feminism’s second wave was distant, too, but its fresh context would lend the fundamental themes of the artist’s work—family, motherhood, the domestic realm—a new place in culture. Eventually, the personal would come to be understood as political, as well as (at least for Bourgeois), the stuff of a heroic mythos and a proper subject for Maman-scaled art.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum.