Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

True to her shadow: a show of intimate works by the late artist.

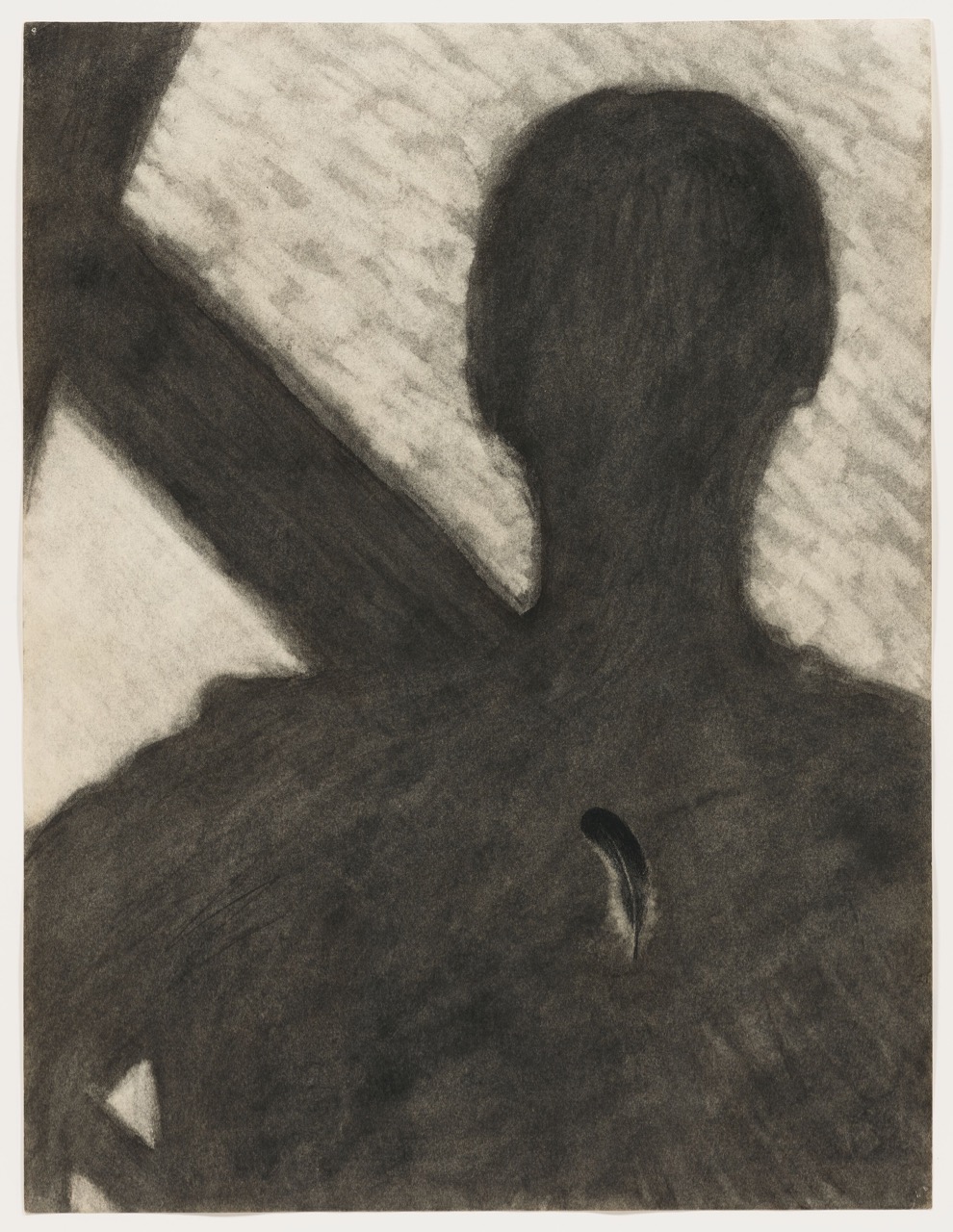

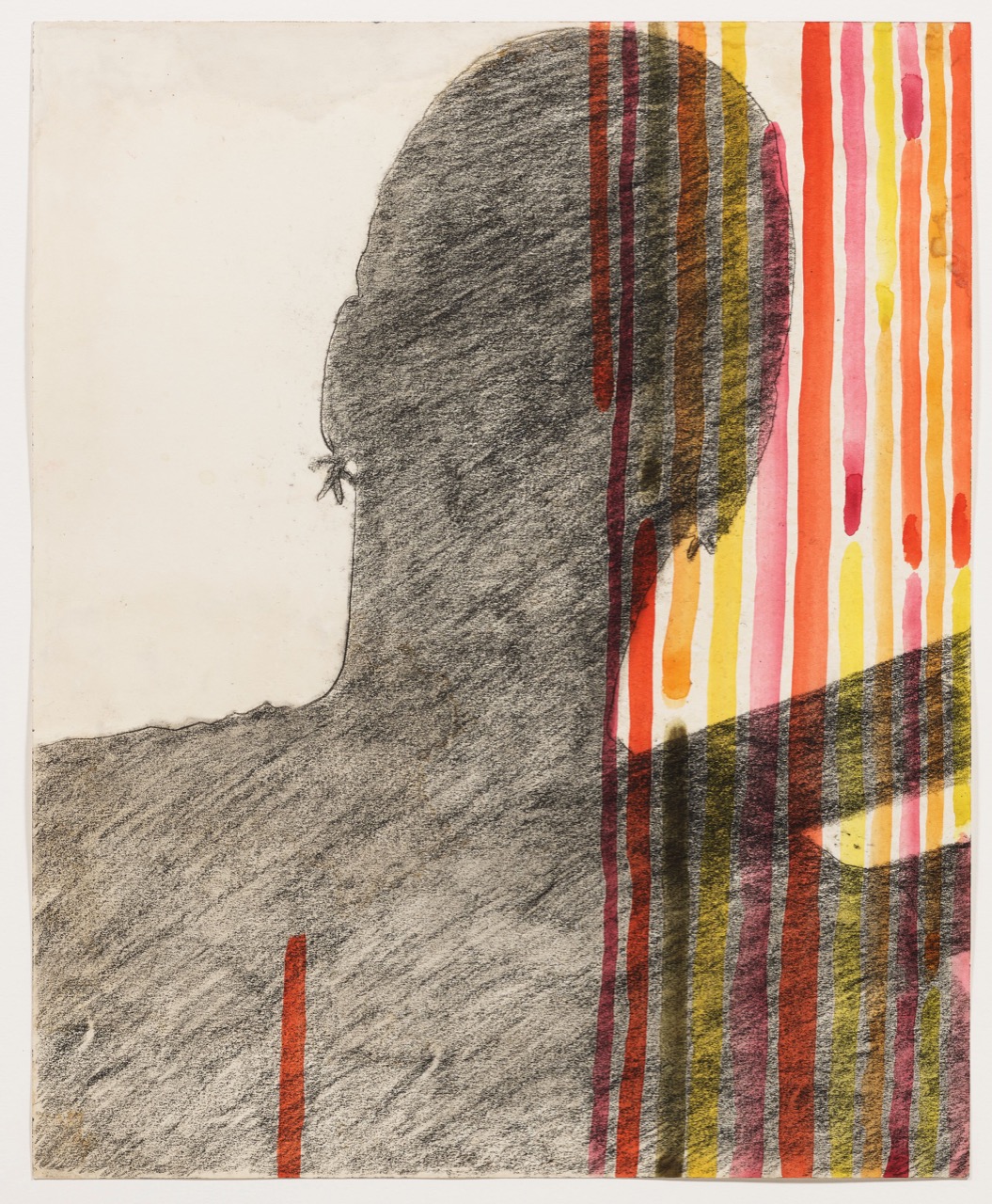

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c. 1970s. Charcoal on paper, 23 1/2 × 17 3/4 inches. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

Luchita Hurtado. Together Forever, Hauser & Wirth, 548 West Twenty-Second Street, New York City, through October 31, 2020

• • •

The Venezuelan-born artist Luchita Hurtado, obscure until recently, would have been one hundred in November. She died last month, with her first career survey, I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn, on pause, due to the pandemic, at LACMA in Los Angeles. (The traveling retrospective originated at London’s Serpentine Gallery, with one more stop planned for the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City.) Her show at Hauser & Wirth’s Chelsea space, bittersweetly titled Together Forever, is thus an outpost of unincluded work—thirty-nine self-portraits, broadly defined, which span the sixties to 2020. The smallish drawings and paintings are stretched thin to fill the cavernous gallery’s ground floor, and perhaps seem adrift for lack of context, or lack of contrast, too: Hurtado’s dense, dynamic abstractions and seductive post-Surrealist feats of foreshortening are the commanding flipside to this more intimate work. Nevertheless—from the forthright likenesses of her face to the captivating meditations on her shadow to a suite of vibrant canvases born of her urgent concern for the earth—these disparate images form a fascinating through line of self-reflection.

Luchita Hurtado. Together Forever, installation view. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

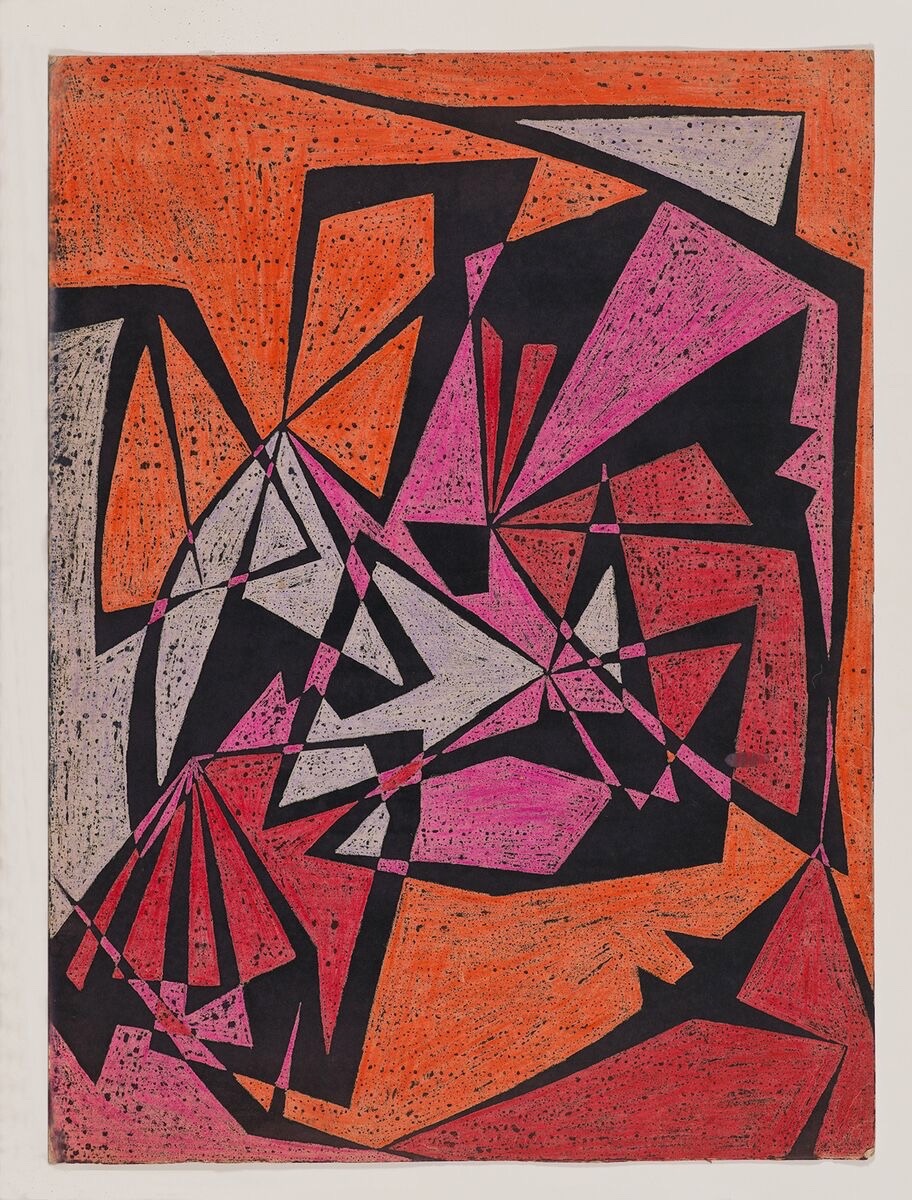

It’s fair to say all this attention is overdue, though Hurtado’s story is not a simple, familiar one of ambitious female talent overlooked, of a woman artist forgotten and rediscovered shamefully late, or of a brilliant outsider discovered for the first time—not exactly. Her protean rigor was accompanied by a curiously private, even secretive attitude toward her art for most of her life. Although active since the 1940s, she didn’t begin to show until the 1970s, and only became a truly active presence in the artworld at the age of ninety-seven. When a trove of her early works was found in 2015, misplaced in the flat files of her third husband (the artist Lee Mullican, who died in 1998), most, if not all of it, had never been exhibited. Nor had she revealed her efforts—astounding compositions of knotted geometry and ecstatic dancing figures informed by Cubist and pre-Columbian art—to her illustrious circle, it seems. (An eye-opening exhibition of these dazzling works from the forties and fifties, at Hauser & Wirth’s Upper East Side location early last year, was my introduction to Hurtado.)

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, 1950. Crayon and ink on board, 23 × 17 inches. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

In almost every account of her extraordinary life, a parade of boldface names from the twentieth-century international avant-garde threatens to overshadow a discussion of her art, yet an accounting of her milieu is unavoidable to some degree. It helps to map the world she was a part of, and the parts of it she refused: she was unaligned with the movements she was immersed in socially, and she wasn’t driven by the demands of a career. Critic Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, in a catalog essay for Hurtado’s retrospective, observes of her decision to create in isolation, “That alone is a remarkable choice with aesthetic, as well as personal, consequences.” Perhaps especially when considering the significance of her self-portraiture.

Hurtado immigrated to New York as a child, and at age eighteen married a Chilean journalist (he left her in 1944 with two young sons). Through her husband she met Isamu Noguchi, and through Noguchi she met Rufino Tamayo and many other artists—the American modernist elite, as well as Europeans who had fled to New York during the war. Her second marriage, to painter Wolfgang Paalen in 1946, took her to Mexico, in the orbit of the muralists as well as Surrealist painters, such as Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo; and then to California, where Paalen was at the center of the Dynaton movement. Later, Hurtado became involved with Mullican; they married and settled in Santa Monica in the fifties, though this was not the end of travel or glamorous friends for the couple. (The artist Matt Mullican is their son.) Chronologically speaking, Together Forever begins around the time Hurtado took possession of her first studio, when she was in her early forties.

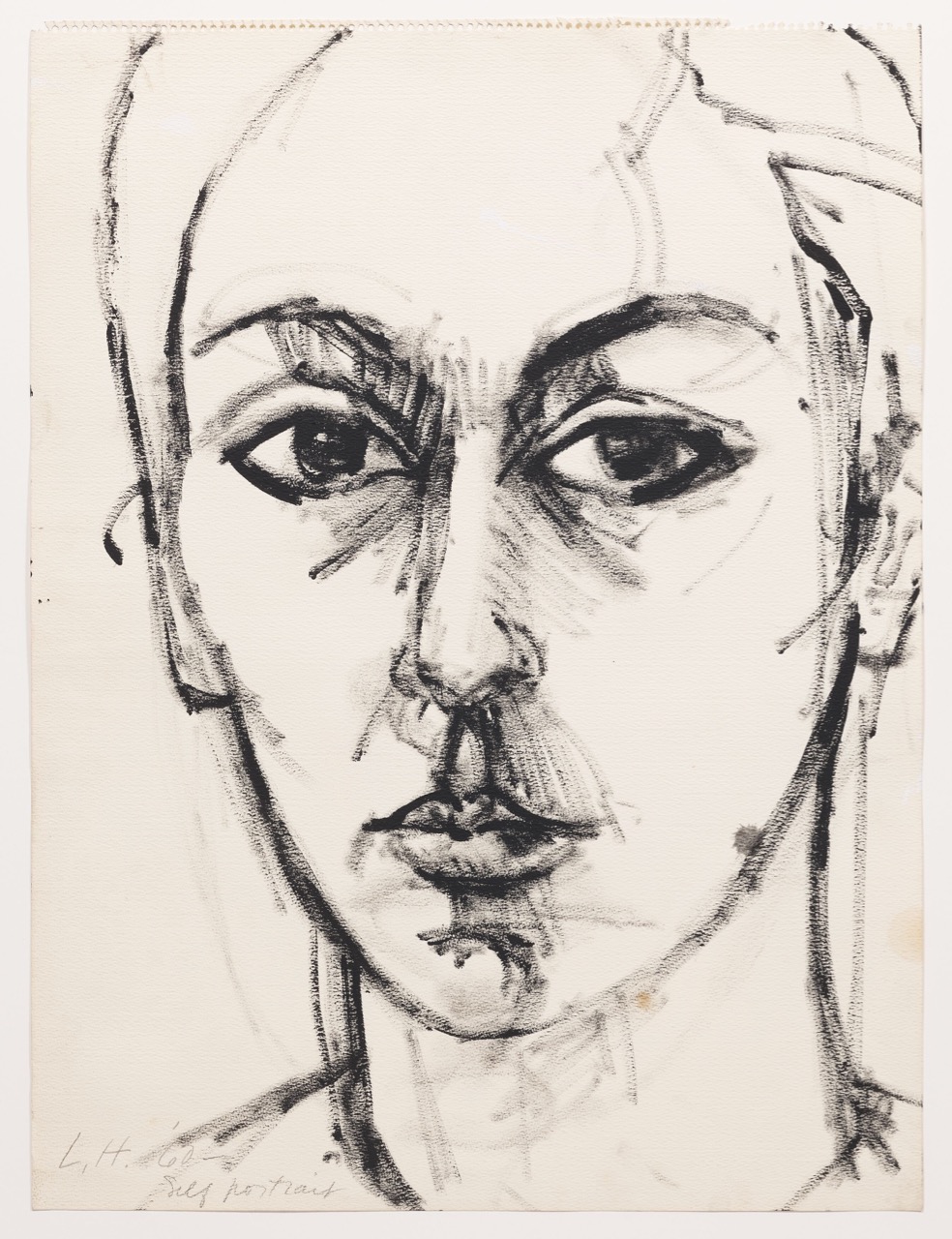

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled (Self Portrait), 1962. Oil on paper, 24 × 18 inches. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

One sketchbook-sized, untitled drawing shows her in 1962. It’s an unsentimental sketch by a trained hand that captures her proportions and expressionless features with appealing intensity. Two other self-portraits from the same era (dated simply “1960s”) are also faithful renderings, in slightly different styles. For Hurtado they may have been warm-ups or throwaways. Here, they’re useful reference points for a “before”: when Hurtado’s skilled self-observation had not yet converged with her established modes of abstraction, when she engaged more with mimetic particulars. She was soon to question long-held assumptions about the depiction of the body and the self.

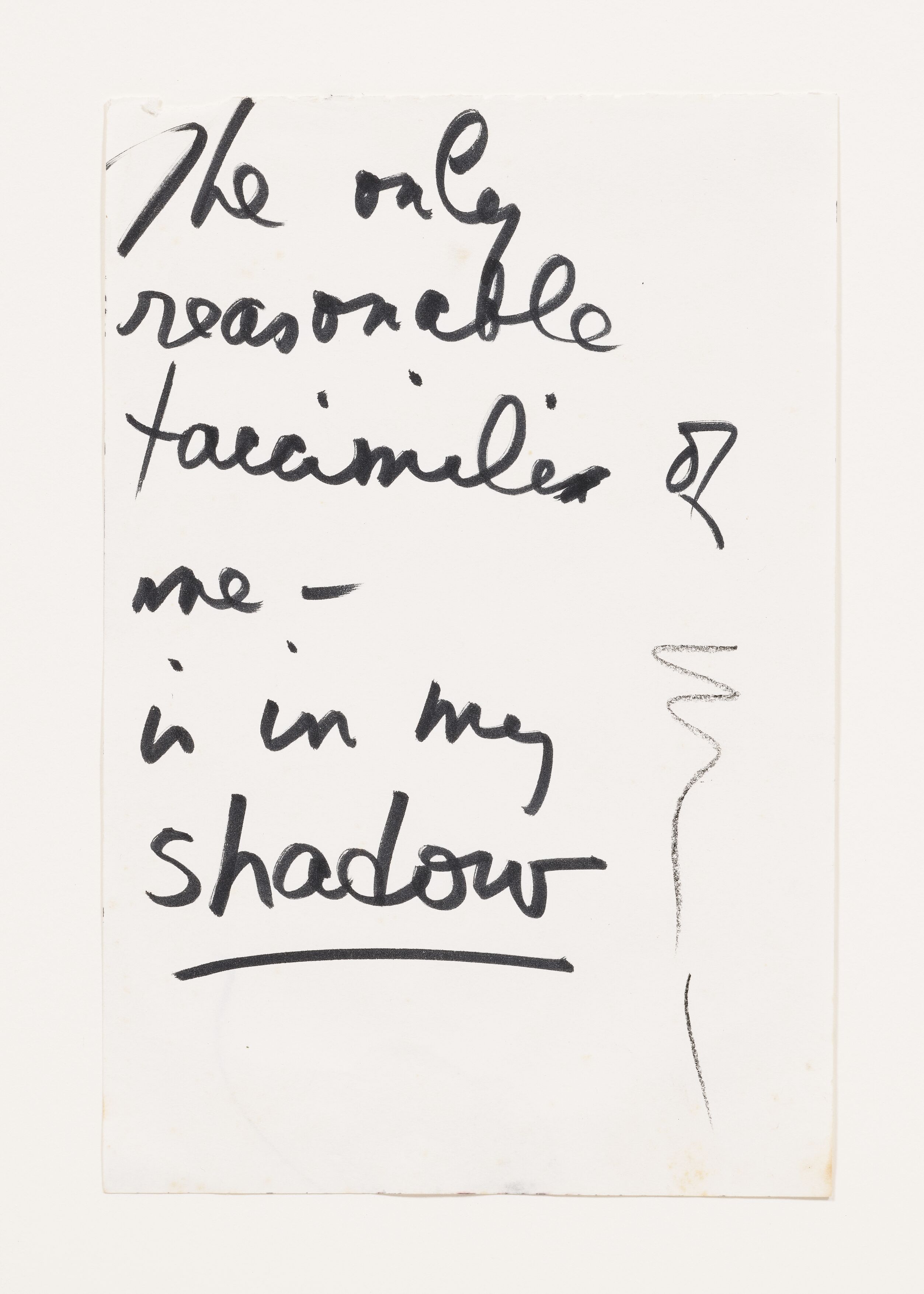

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c. 1970s. Ink on paper, 8 × 5 1/2 inches. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

“The only reasonable facsimile of me—is in my shadow,” she scrawls on a text drawing from the seventies, providing an epiphanic and to-the-point introduction to her exquisite series of silhouettes. (These could have been their own beautiful show, installed in a reasonably scaled room.) Hurtado favors graphite or charcoal in dusky, dusty monotonal works; black ink on stark white for a group that resemble tracings. One drawing, a wildcard, is partially curtained with watercolor stripes in a citrus palette.

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c. 1970s. Charcoal and watercolor on paper, 17 × 13 3/4 inches. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

In these shadow images you recognize the contours of her head and neck in each cropped framing, but of course, her features are effaced. They are gone too in a parallel practice of hers in the 1970s—colorful, modeled works (in which Magritte-style floating fruit sometimes appear) that show her body from her own point of view: standing, looking down, and thus headless. This radical approach to the self-observed figure echoes other feminist investigations of the era, and, in fact, Hurtado joined with the California contingent of the women’s art movement around this time, shedding, at least for a moment, her reticence to showing. In 1974, she installed her first solo exhibition, in Los Angeles, at the Woman’s Building (a space founded by Judy Chicago, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, and Arlene Raven). Perhaps working for decades in independent solitude was preferable primarily to working in the shadow of men? Fresh political conditions (and the absence of young children) inspired her.

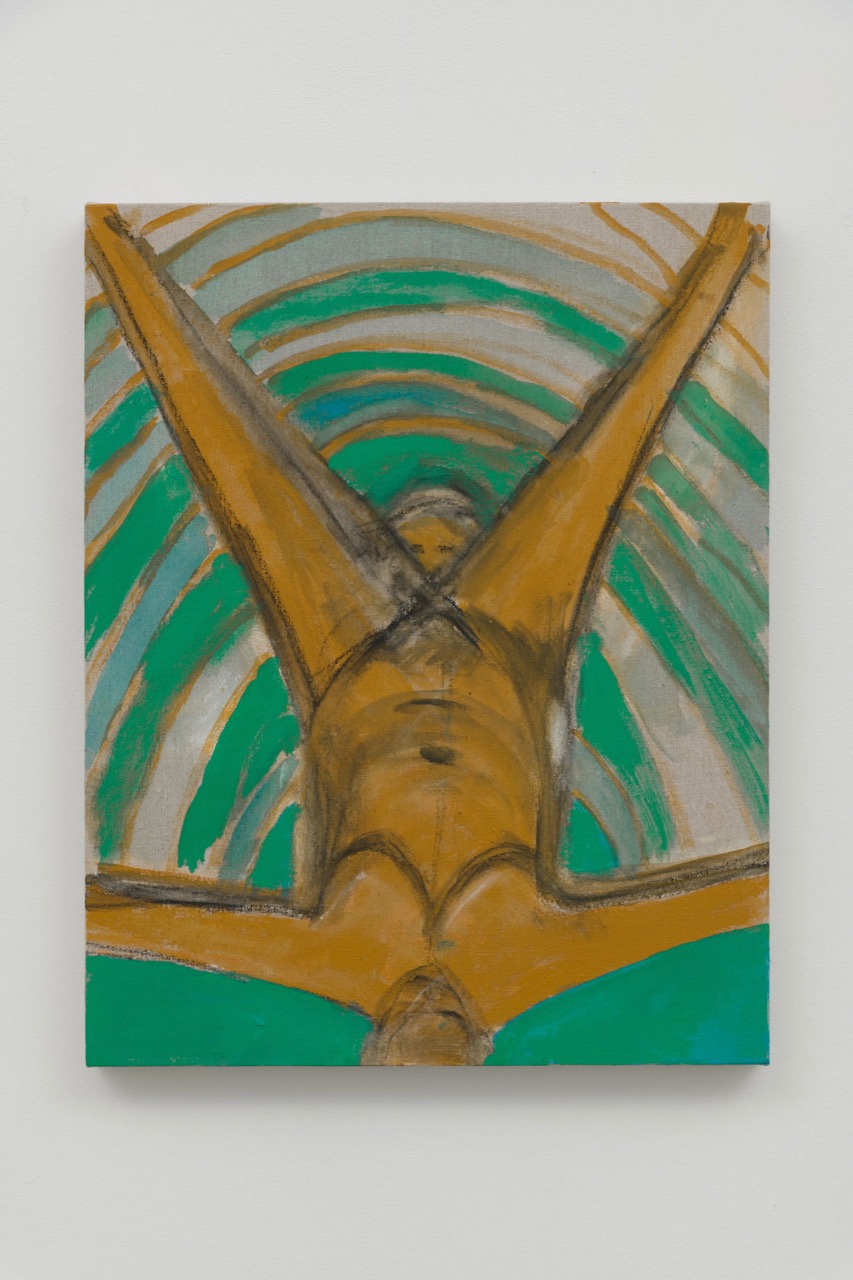

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled (Birthing), 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 24 1/4 × 19 1/4 × 1 3/4 inches. © Luchita Hurtado. Image courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

Together Forever includes none of these “looking down” works, which is unfortunate, because their landscape qualities—the body’s naked curves resemble a succession of receding hills from this vantage—gain new significance as a representation of embodied experience vis-à-vis Hurtado’s last artistic themes. Environmental catastrophe comes to the fore in her paintings from 2019 on, though their imagery is not that of apocalypse but rebirth—and they are less self-portraits than passionate dissolutions of the self into an archetypal birth image. In a number of these, installed at the exhibition’s end, we share the artist’s (or the archetype’s) point of view, experiencing for ourselves the merging of the foreshortened mother figure and the earth. The forceful geometric symmetry of her parted legs are mountains; the head of a crowning baby appears at the horizon.

“The most interesting thing for me now is to make sure that the planet is going in the right direction,” Hurtado said in an interview last year. “I keep the words ‘sky, water, earth, fire’ in my mind. Those are the elements, and that’s what my work has come to be about. That’s what I’m about.” Perhaps—in that her art has always pursued elemental or spiritual truths, and always challenged the divide between the personal and the mythic—this final foray into abstract figuration illuminates what she has always been about. Though this exhibition seems almost designed to dissatisfy with its omissions, I’m grateful for what is here to see. We’re lucky she didn’t wait to be discovered, but finally felt free, and driven, to share.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.