Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

The artist’s show broaches a surfeit of ideas about survival and surveillance, visibility and vulnerability.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, curated by Vivian Crockett with Ian Wallace, New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through January 14, 2024

• • •

The artist was not present during my first visit to her new exhibition, Nothing New. The glass-walled lobby gallery spanning the far end of the New Museum’s ground floor, which Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo has transformed into a living space—sort of—was quiet, an open can of Sprite the only sign of life. I was disappointed, then relieved. The installation, with its transparent front, resembles a strange three-part dollhouse. A bedroom, screened off by shoji dividers, is centered between an austere display of six cannabis plants on tall white pedestals to the left and a small Japanese-style rock garden to the right. This last vignette might be seen as an oasis, but beneath the sunless enclosure’s bleakly institutional overhead lighting, it feels like a giant terrarium. I don’t want anyone to live here, I thought. There’s nowhere to hide but under the covers.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

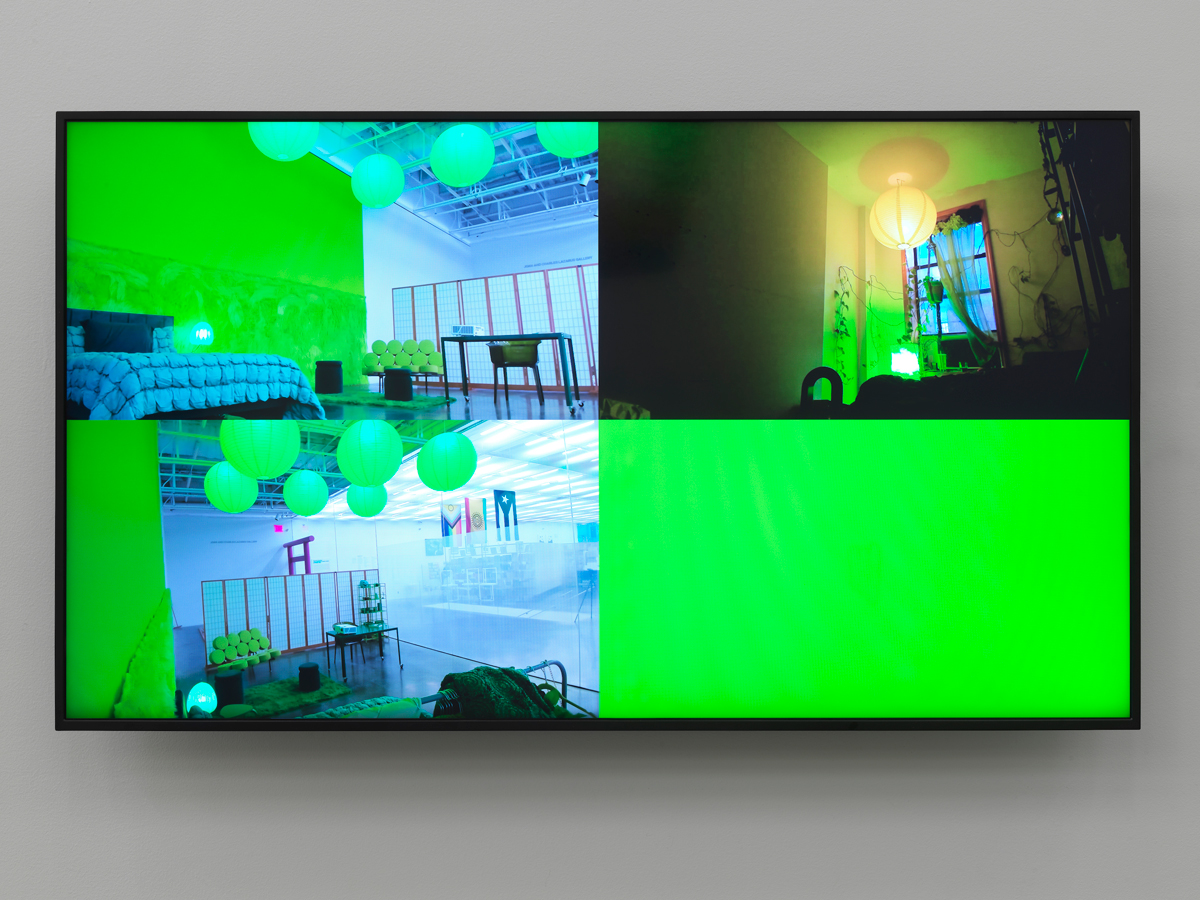

A video display mounted outside the gallery, on a perpendicular wall in view of the lobby’s café seating, shows a grid of live surveillance feeds from cameras positioned both within the installation and off-site, one monitoring Kuriki-Olivo’s actual bedroom. She was nowhere to be seen there, either. Waiting for something to happen, I took in the green décor of her public bedroom—its nine big paper lanterns (identical to the lonely one hanging from the ceiling at home, visible on-screen) and fake fur–lined walls, the scattered biomorphic bath mats that look like cartoon lily pads or islands of moss, a glowing LED sign that spells “Jade” on the floor.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

By the indoor forest of leafy marijuana, a wall label explains the cultural, spiritual, and medicinal uses of the plants and their meaning to the artist, including the importance of CBD in her recovery from brain surgery. (She had a cancerous tumor removed in 2010.) A dark rectangle of thirty MRI scans, which obscures a section of the wall here, memorializes the experience, while the radiological photos, as images of the inside of her head, become an acutely intimate, but also a starkly dissociative, self-portrait. Contradictions like these—the collision of the inscrutable and detached with the urgent and sincere—define the complicated show.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

The extensive exhibition text makes no promise that the artist will always be visible in the installation, stating only that it will serve as a “mise-en-scène for her daily activities.” Yet it cites as precursors Marina Abramović and Tehching Hsieh, whose best-known endurance works hinge on the spartan simplicity of (and strict adherence to) predetermined rules; it frames Nothing New as a three-month exercise in self-exposure. Kuriki-Olivo’s presence, in the museum or on-screen, is meant to constitute a further step away from the enigmatic persona and anonymized gestures of her earlier practice—“towards radical visibility,” we’re told—a journey initiated in 2018, when she began living openly as a trans woman. It could be that this premise is a feint; that she intends to turn a conventional understanding of visibility (or endurance art) on its head. Either way, a high bar has been set for success.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Working under the name Puppies Puppies since 2010, the artist has, in past performances, appeared in disguises, mass-produced costumes (Party City–type iterations of SpongeBob SquarePants, Voldemort, and Lady Liberty among them), achieving a meme-come-to-life presence. In a legendary 2015 solo show at the adventurous Queer Thoughts (which sadly closed this fall), the artist—otherwise dressed only in a loin cloth—deployed a Gollum mask to more startling and poignant effect. But the cagey conceptualism of these wearable readymades eventually took on an unwanted significance: “It means something very different to be hidden as a trans woman,” she has said. Last year, Kuriki-Olivo, whose Taíno and Japanese ancestry is also a subject of her work, mounted a show at Galerie Barbara Weiss in Berlin featuring a series of in-situ vinyl text pieces. Her relinquishment of cooler or absurdist strategies—at least for the moment—was made clear in anguished and exasperated first-person declarations, such as the unapologetic line “I’M SORRY MY IDENTITY IS A PART OF MY WORK.”

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Text plays a role in Nothing New, too. Behind the museum café counter, which faces and runs parallel to the installation, another accumulation of green things, in hues from neon to hunter, fills the wall. Packaged products such as Fabuloso all-purpose cleaner, lime La Croix, and jalapeño potato chips form a verdant monochrome, above which a sign, its reflection appearing on the surface of the installation’s glass wall, quotes Sylvia Rivera, trans advocate and heroine of the Stonewall uprising. “We have to be visible. We are not ashamed of who we are,” it reads, underscoring the activist quality of Kuriki-Olivo’s endeavor. In this light, the artist—or the cordoned-off compartment that holds her place—occupies the institutional space in harrowingly vulnerable defiance of the current lethal cascade of right-wing legislation and vigilantism, the agenda that aims to eradicate trans people from public life. But her use of Rivera’s words to invoke one sense of visibility—as a political imperative in social struggle—is in tension with other notions of representation and survival here. Maybe refusal and absence show the artist more clearly, in silhouette, as the negative space between these green things; maybe invisibility is preferable if the option is to live as a spectacle, behind glass.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

During my second visit, the artist was beneath a puffy green comforter, purse tossed on the bed, looking at her phone. A fogging device made the barrier between her and me intermittently opaque, sometimes switching on and off quickly, like an eye blinking in bursts. The interruptions forced me to watch the scene more intently, to stare obscenely in effort and frustration. The other option was to watch a differently mediated view of her in the bed on the nearby screen, which felt, after a moment, just as bad. Of course, there was also the option to look away.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

There is so much going on here, a surfeit of ideas possibly, a lot I haven’t touched on. The conceptual excess and mixed messages might not be such a problem, though, were it not for the curatorial over-explanation of the artist’s intent. The show might reflect “on the art world’s power dynamics and financial structures and how they mirror those of sex work”; it might explore “new registers of transparency and obfuscation”; Kuriki-Olivo might be “eliding tokenization and reductive narratives of racial and trans identities.” Eleven days in, I think it’s too early to judge. Nothing New is incomplete, still unfolding. Of course, if I’m accusing the exhibition text of premature interpretation, am I doing the same? Today, the show seems to propose something interesting about representation through institutional intervention, through absence rather than inclusion, but, by January, it might say something else.

Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo): Nothing New, installation view. Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

On my third visit, I came in the late afternoon and sat working at one of the café tables in the lobby until the museum closed. Perhaps I came at the wrong time, again. I kept an eye on the video feeds, as the bedroom was empty. When I was gathering my things to leave, I saw movement on the nearby screen. In the top-right corner, a leg emerged from deep shadow, to rearrange itself beneath the covers. I froze, watching, but that was it.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and musician in New York.