Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

An artist’s sparkling time machine transports viewers back to San Francisco’s first Black-owned gay bar.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, 2022, installation view. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Adam Reich.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, organized by Legacy Russell, the Kitchen (in collaboration with the Studio Museum in Harlem),

512 West Nineteenth Street, New York City, through March 6, 2022

• • •

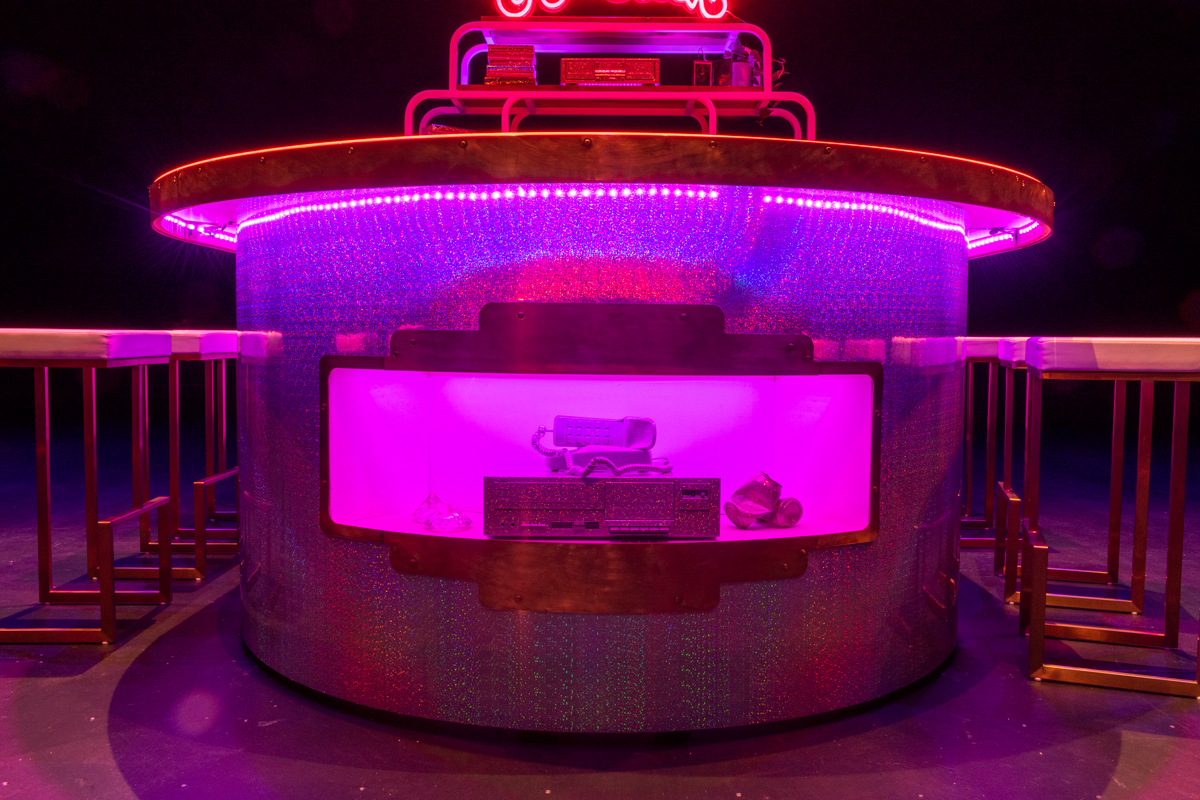

In the darkness of the Kitchen’s cavernous main space, curved planes of laminated glitter form the horseshoe-shaped island of Sadie Barnette’s installation, The New Eagle Creek Saloon. Surrounded by barstools, the reflective structure seems to levitate a little—thanks to the glow of hidden purple LED striplights and the visual pull of a pink neon sign that crowns the archway of open shelves at the back. The illuminated bubble script reads “Eagle Creek.” The artist’s sculptural invocation of the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco—which her father Rodney Barnette opened in 1990 and operated until 1993—is stylized, abstracted. (The historic establishment featured a bar of dark wood, and while it had a neon sign, it wasn’t pink.) Her version looks less like the excised core of a real nightclub than a phantasmic projection, a metaphysical representation, or a small spacecraft—especially when a DJ takes the place of bartender at the helm, performing in the round.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, 2022, installation view. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Adam Reich.

This is Barnette’s first East Coast iteration of the work. (It debuted on the West Coast in 2019, at the Lab in San Francisco’s Mission district, not far from the New Eagle Creek Saloon’s Market Street location.) It’s also the inaugural curatorial project of the Kitchen’s new executive director and chief curator, Legacy Russell, who presents it with the complementary, or dovetailing, programming of madison moore’s Kitchen residency, Nightlife-in-Residence. The artist-scholar and DJ, who’s writing a book titled Dance Mania: A Manifesto for Queer Nightlife, is hosting a series of Saturday Sessions with house-music and nightlife luminaries in the exhibition throughout its run. The series opened on January 22 with a public conversation between moore and the Chicago-born DJ Shaun J. Wright, followed by a live set. (The following week featured Nita Aviance; other scheduled guests include Juana and TYGAPAW.)

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, installation view. Pictured, Shaun J. Wright and madison moore, Saturday Sessions event, 2022. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Paula Court.

Barnette has made her father’s history the subject of her art before. In earlier works she used fuchsia spray paint, glitter, and rhinestones to garishly, girlishly embellish and redact pages from his COINTELPRO file—a nearly five-hundred-page collection of documents that detail his membership in the Black Panther Party and his political activism, as well as information about his family. Archival materials figure importantly in this newer installation, too. A closer look at the artist’s fairy-dusted memorialization of her father’s bar reveals its shrine-like aspect; it functions as a display of mementos, artifacts, and relics.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, 2022, installation view. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Adam Reich.

A vintage snapshot—a happy group portrait of five men holding drinks—is framed behind the bar, accompanied by a votive candle and sticks of palo santo. Amethyst clusters or other crystals, a Whitney Houston album, and glitter-encrusted books, beer cans, and stereo equipment are tucked away on shelves or displayed in niches. In photos shown beneath the countertop’s glass, images of revelry—a raised champagne glass, a cake-cutting, a man leaning in to kiss another man—attest to “a friendly place with a funky bass for every race” (as the saloon billed itself), while also evoking loss as wistful mementos of a distant time. But it is in Barnette’s accompanying publication, a zine with a hot-pink cover, available in the Kitchen’s lobby, that she tells more of the story; or rather, by assembling these newspaper clippings and memorabilia, she invites readers to puzzle it together.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, 2022, installation view. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Adam Reich.

After a few pages of reproduced ephemera—including a frontispiece emblazoned with a reproduction of a silver-foil Eagle Creek matchbook, worn around the edges, and a typewritten, discolored equipment inventory—the photocopied volume begins with a short profile of Rodney Barnette in a local paper (undated, but from the early 1990s, when the bar was open). The text traces his work, twenty years earlier, with the National Committee to Free Angela Davis, his subsequent founding of Third World Gay People Against Political Oppression, and his involvement in San Francisco politics. The writer, Kelvin Fincher, frames Barnette’s purchase of the saloon as inseparable from his activism: it was, in part, a response to the discriminatory practices of white-owned gay bars, which often demanded multiple forms of identification from patrons of color at the door; and it was meant to serve a historically oppressed community, now facing a new crisis. “We’re fighting a war here,” Barnette is quoted in the piece. “The government isn’t paying much attention to AIDS—especially as it effects the black gay community—it is up to us to confront these issues head on.” The zine’s next article, from a 1993 Bay Area Reporter, details an interactive, touch-screen HIV/AIDS-prevention educational game geared toward Black queers, which could be played in a kiosk at Eagle Creek. And later, amid photos and event flyers, comes a reminder of other perils. A racist crime-blotter item reports the murder of a white gay man, noting he frequented the bar, insinuating that his preference for Black men and so-called “rough trade” put him in danger. Rodney Barnette’s response to the editor is printed on the facing page.

His daughter’s conceptually restrained approach—the younger Barnette presents these items in her publication without comment—is somewhat at odds with the spangled aesthetic of her other art, but it hardly renders the work impersonal. Laid out with a minimalist scrapbooker’s care, the zine is both a key to her installation’s symbolic and historical meaning and a declaration of her intimate relationship to it. She appears as a beaming child in photos of her family, all of them dressed fabulously, we’re not told why, in opulent Renaissance dress.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, installation view. Pictured, Shaun J. Wright, Saturday Sessions event, 2022. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Paula Court.

In another deft interlacing of The New Eagle Creek and moore’s residency, the DJs who perform on Saturdays choose videos to project on a screen behind them, which then play, along with a recording of their set, during exhibition hours throughout the week. Wright’s selections included, among other things, T.V. Transvestite (1982), documenting a House of LaBeija Ball in Harlem, and clips from The New Dance Show, a Detroit cable-access production from the 1980s and ’90s that focused on local house and techno. The dreamy effect of film used as a component of dance-club atmosphere—when image and beat only incidentally sync, but fuse on another wavelength—was entrancing when Wright and moore’s talk segued into an afternoon rave at the Kitchen.

Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon, installation view, Saturday Sessions event, 2022. Courtesy the Kitchen. Photo: Paula Court.

The transporting installation was differently powerful when I visited a few days later and found myself alone with Barnette’s art, the grainy vintage video, and music—not in the background, but shaking the empty room with bass. Several generations of club culture seemed to converge around her reimagination of a bygone Black queer space, and in the oddly contemplative ambience, Barnette’s bar was more clearly an altar and a sparkling time machine, as well as a dance-floor centerpiece.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.