Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

In his new show, the painter reworks vintage atmospherics.

Salman Toor: How Will I Know, installation view. Pictured, from left to right: Bar Boy, 2019; Tea, 2020; Two Men with Vans, Tie and Bottle, 2019; Nightmare, 2020. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Salman Toor: How Will I Know, organized by Christopher Y. Lew and Ambika Trasi, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through April 4, 2021

• • •

The lamplit and smartphone-illuminated, sepia-blush-celadon world of Salman Toor’s art is filled with moments of maskless intimacy. In his current solo exhibition, How Will I Know (named for the 1985 Whitney Houston song), on view in the lobby gallery of the Whitney Museum, exquisite paintings depict his young subjects gathered in apartments, on a stoop, on a street corner, and at a crowded gay bar. The artist, who is from Lahore and now lives in the East Village, favors protagonists much like himself—queer South Asians in the era of Trump’s travel ban; lanky brown men with an epicene beauty and bohemian glamour. Given the acute longings endemic to our present circumstances, Toor’s scenes of closeness and spontaneous encounter, his renderings of a community (or demimonde), real or imagined, strike a powerful note of something like nostalgia.

But they would in more ordinary times too, I think. In the artist’s hands, the situations and accoutrements of contemporary life are suspended in time; he enfolds them in vintage atmospherics, magically smoothing anachronistic disjunctions with delicate impasto gestures and a melancholic style informed by diverse strains of sumptuous, camp-adjacent beauty, such as Watteau’s fêtes galantes, as well as the intoxicating cartoon chiaroscuro of classic Disney movies—Pinocchio (1940), in particular.

Salman Toor, Four Friends, 2019. Oil on panel, 40 × 40 inches. Courtesy the artist.

That animated film comes to mind not only for its brooding ambience and fairytale sense of an indeterminate historical past, but because Toor’s figures have a marionette-like bearing—sloped shoulders, wayward limbs, even curiously elongated noses. Such physical traits are pronounced in Four Friends (2019), which captures an evening of uninhibited socializing in a cramped living room. One figure in short shorts has fallen to his knees in a theatrical display of joyous supplication to his shimmying, neckerchief-wearing dance partner. Both of them appear to have long, weightless arms, as though invisible strings at the wrist hold them aloft. Two other men slouch together on a Rococo loveseat, one sharing something with the other—of little or only passing interest, it seems—on his phone.

Salman Toor, Bar Boy, 2019. Oil on plywood, 48 × 60 inches. Courtesy the artist.

The central figure of Bar Boy (2019) gazes at his screen, too, finding a moment of solitude (or filling one) as all around him boys cluster or pair up in a wonderland of têtes-à-têtes and canoodling, drinks in hand. In both paintings, low-key debauchery and a phosphorescent green glow establish that the action takes place long past cocktail hour (Toor favors rich variations on the hue for nocturnal scenes), while digital technology and LED fairy lights tether it to our time. But the men’s pointy, thumblike noses put them, at least partly, in Pinocchio’s realm of enchantment.

The more fantastic Parts and Things (2019) is an exceptionally dark version of Geppetto’s workshop, you could say; the dramatically symbolic, vertical composition features a desolate closet. A single bare bulb is the dim spotlight for an indistinct pile of things: a pink boa, maybe some wigs, and an assortment of severed—or disassembled—limbs and heads, which look as though they could belong to the four lovely friends, or the bar boy, described above.

Salman Toor: How Will I Know, installation view. Pictured, from left to right: Parts and Things, 2019; Bar Boy, 2019; Tea, 2020. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

The emerald gloom of this vanitas still life recasts the painter’s hallmark nightlife color as nightmarish, no longer connoting louche liberation, but rather horror and death—or, less hyperbolically, the dreadful uncertainties and false starts of self-construction; the inevitable, messy accumulation of cast-off props and identities.

In Pinocchio, the woodworker’s wish upon a falling star is for his freshly completed marionette to become a real boy; Toor, I get the feeling, harbors some parallel, more complicated, hope or desire. His boys, as fictionalized avatars, rehearse possible variations on a life; and as oil-painted figures redolent of past styles, they revise art-historical tropes along the way. The canon looms large in every picture here, simultaneously pilloried and resuscitated, Western painting’s conventions vis-à-vis race and gender brought into sharp relief by the artist’s easy adaption of its painterly tricks—for Toor, this undertaking is as erotic as it is academic, maybe more.

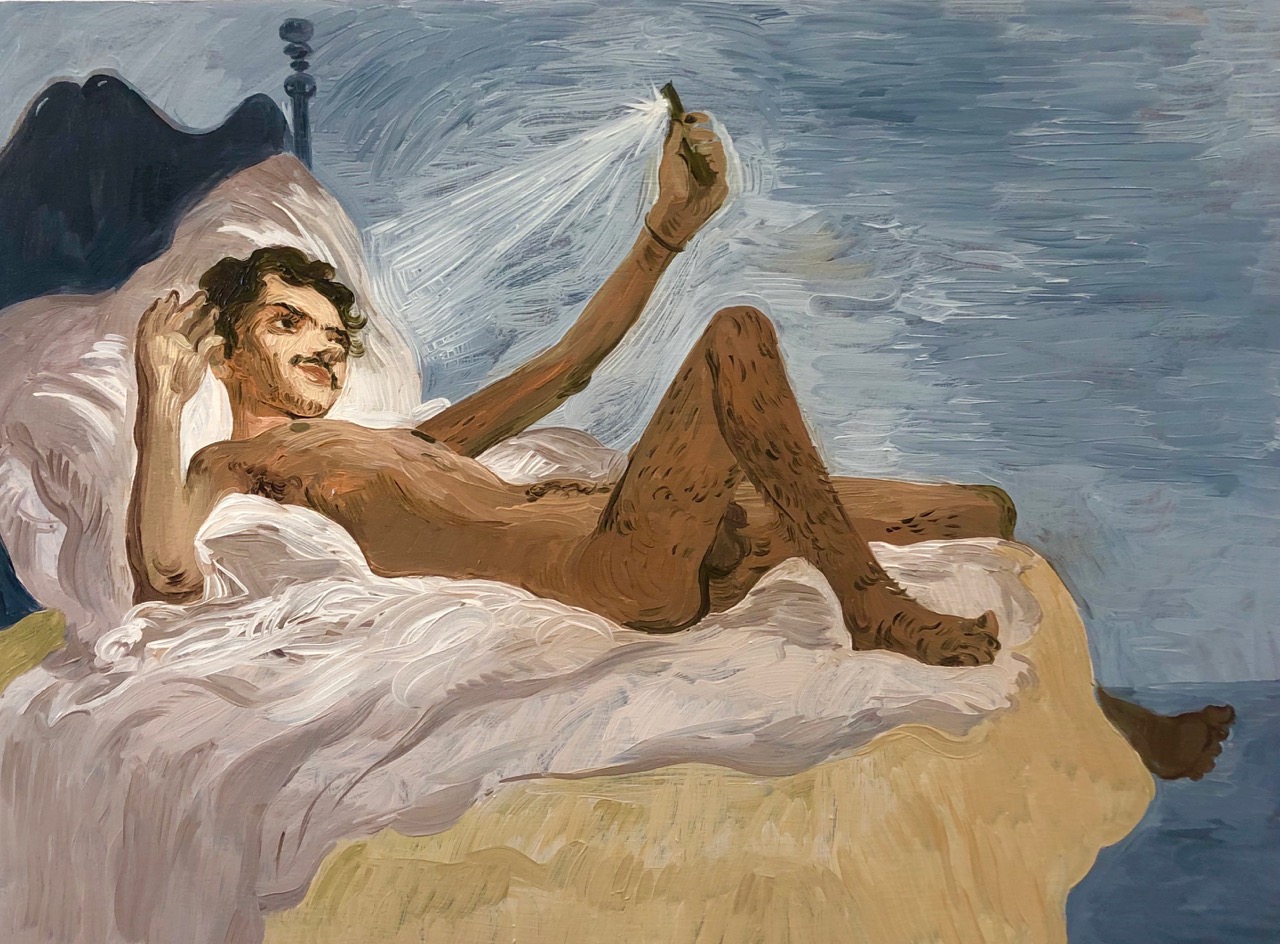

Salman Toor, Bedroom Boy, 2019. Oil on panel, 12 × 16 inches. Courtesy the artist.

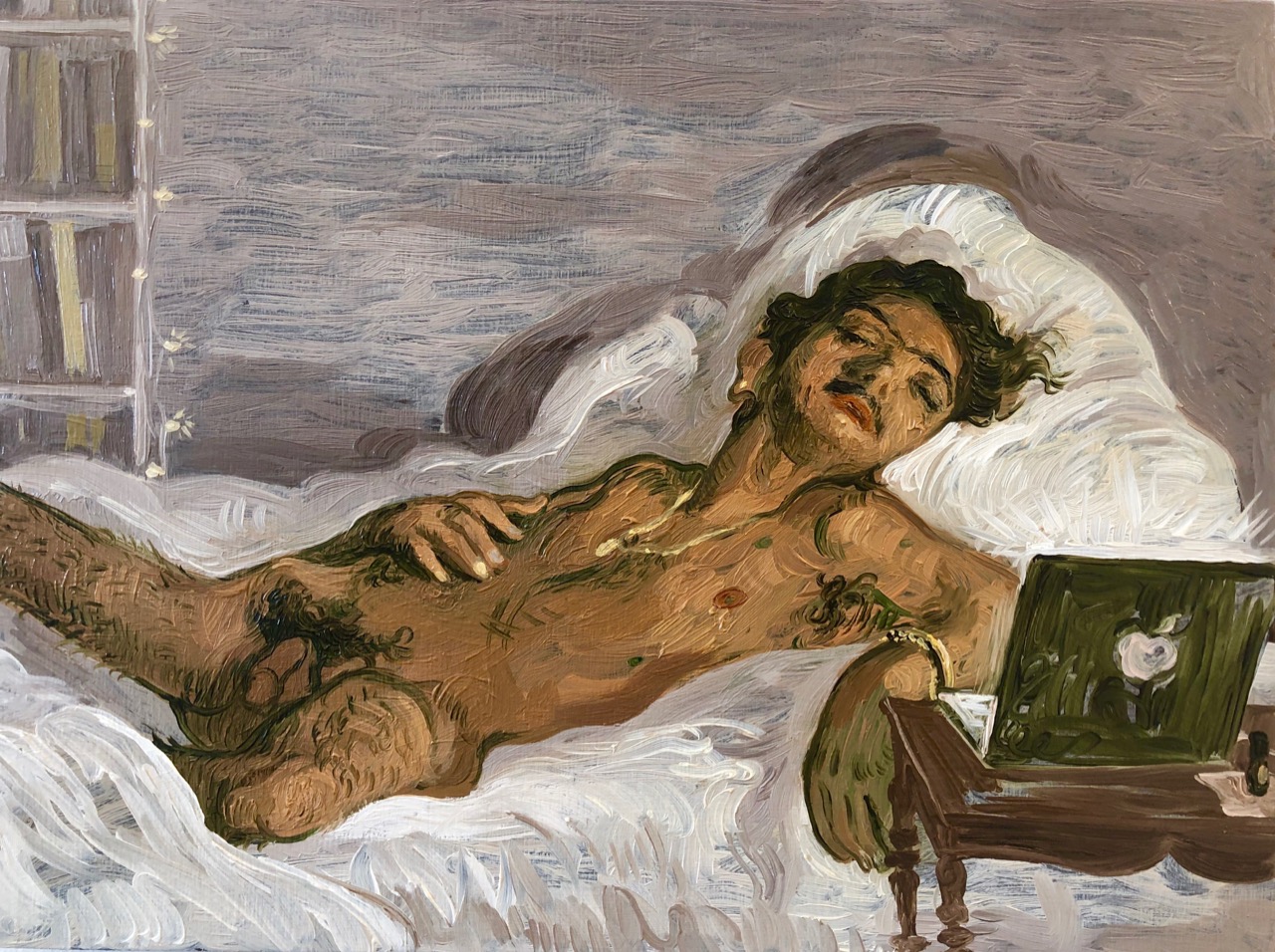

Two works on view contribute gorgeously to the storied genre of the reclining nude. Rendered in powder-pastel palettes, Toor’s boudoir portraits each feature a young brown man sprawled on clouds of bedding. The beatific subject of Bedroom Boy (2019) basks in a beam of creamy light, as though speaking to an angel, as he holds a device at arm’s length to snap a selfie. Sleeping Boy, also from last year, shows a figure dozing in a laptop’s aura, the imperious languor of his sexy pose possibly a response to nineteenth-century Orientalism—the Neoclassicalism of Ingres, for example, whose harem scenes now read as voluptuously sinister portraits of colonialism and sexual hierarchy. On the other hand, it might be an homage to the smoldering, Postimpressionist figuration of the Hungarian-Indian painter Amrita Sher-Gil. (Toor cites her as an early influence.) I think it’s likely both.

Salman Toor, Sleeping Boy, 2019. Oil on panel, 9 × 12 inches. Courtesy the artist.

While social critique—in registers of insouciance, celebration, and sadness—is embedded throughout How Will I Know, it appears most bluntly in a pair of works (from a larger series) that find Toor’s characters in airport security lines, dejected, their pockets emptied. The uncommonly muted, beige composition Two Men with Vans, Tie and Bottle (2019) portrays the travelers (a couple?) in listless contemplation of the miscellanea they’ve produced for inspection. In this image, and in the related Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug (2019), the viewer is positioned across the conveyer belt from the “suspects”; we are the authorities. Our perspective entails no voyeuristic pleasure, no illusion of participation or reciprocity—instead it uncomfortably reproduces the dehumanizing pre-boarding ritual, putting us on the side of the racist system.

Salman Toor, Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug, 2019. Oil on canvas, 43 × 36 inches. Courtesy the artist.

The men, out of their element, in the most unromantic of settings, are sapped of their luster—unpretty and even unfashionable, their sartorial signifiers meaningless in the unwelcoming public space. These vignettes stand as harsh foils to those that star Toor’s foppish characters in their splendor. In the street scene The Smokers (2018), for example, though a policeman patrols the background, his threat feels distant for the moment; the foreground is occupied by a chatting trio, and commanded by its nearmost figure, a pensive smoker leveraging the foolproof allure of a French-sailor silhouette as he leans, poised, against a dusky building, I imagine near the entrance to a bar.

Salman Toor: How Will I Know, installation view. Pictured, from left to right: Bedroom Boy, 2019; Stoop, 2020; The Smokers, 2018. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

In this contrast, between the airport and queer space, it becomes clear that Toor’s boys come to life in context; they are cobbled together from prized references, everything from Whitney Houston to Querelle; they make sense in relation to one another and their particular histories. The principle that one can lose confidence or coherence in isolation—that the “parts and things” that flourish at parties turn macabre when shoved in the closet—perhaps rings especially true in the dog days of social distancing. But this sublime show, which was meant to open in March, delivers the old and always difficult lesson in a refreshingly, brazenly sentimental, and politically incisive way.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.