Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Guns, cartels, murder: the Mexican artist makes work at the edge of taboo.

Teresa Margolles, Super Speed / El Paso, Texas, 2020. Pigmented inkjet print of box of 24 cartridges purchased from Walmart, Gateway Blvd, El Paso, TX, 26 × 35 3/8 inches. © Teresa Margolles 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle.

Teresa Margolles: El asesinato cambia el mundo / Assassination changes the world, James Cohan, 48 Walker Street, New York City, through

March 1, 2020

• • •

For Teresa Margolles, death is a substance that sanctifies—or contaminates—her work. At the same time, her unflinching art fights such superstitious or sentimental notions. For more than two decades she has sought to expose the decidedly un-mystical, sociopolitical, economic nature of death; of who dies, at whose hands, for what. In an austere exhibition at James Cohan’s spacious Tribeca gallery, objects as different as a Walmart receipt, couture designs, and a pair of concrete benches embody this defining tension.

Now based in Madrid, Margolles is from the city of Culiacán in Sinaloa, Mexico. She trained as a forensic pathologist and worked in a Mexico City morgue in the early 1990s. There, witness to the endless influx of victims of drug trafficking–related conflict, she came to believe that much can be learned about a society from its hidden treatment of the unclaimed, or destitute, dead. In past exhibitions she has filled rooms with bubbles or fog made with water used to prepare bodies for autopsy; hung fabric stained with the bodily fluids of corpses; and, for the 2009 Venice Biennale, brought family members of murdered people to mop the floors of the Mexican Pavilion with rags soaked in diluted blood. Margolles uses the sensory discomfort of death’s materiality—and in the last performance mentioned, the social discomfort of privileged viewers confronted with domestic labor’s marginality and vulnerability to violence—to examine the global economy’s role in the devastating problems of her country.

Teresa Margolles, La Búsqueda (2), 2014. Intervention with sound frequency on 3 glass panels. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

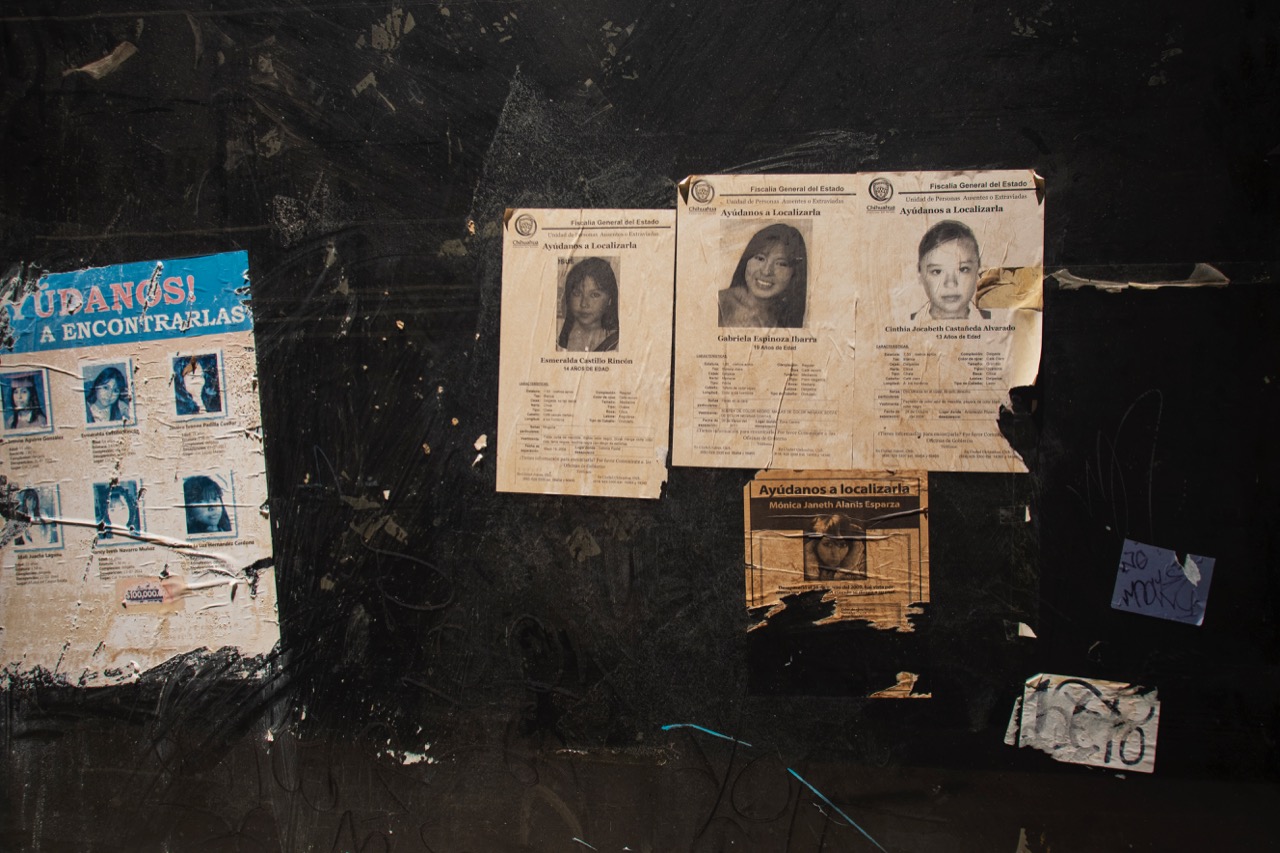

Operating always at the edge of taboo, risking accusations of disrespect for the dead, she successfully walks a fine line where others have stumbled badly. For the 2019 Biennale, Swiss-Icelandic conceptualist Christoph Büchel parked, outside the Arsenale, near a café, the wreck of a fishing boat that sank in the Mediterranean in 2015 with as many as 1,100 migrants in its hold. The battered vessel struck an unfortunately repellent note as a misplaced memorial, an ineffectual indictment, or perhaps worst of all, an expensive stunt. But Margolles, at the same Biennale, installed three dusty glass panels, transported from Ciudad Juárez, wheat-pasted with tattered flyers for missing women, to critical accolade. Unlike Büchel, Margolles has a personal investment in the communities directly concerned with her piece, a fact that ballasts her solemn provocation with ethical credibility. She also presents her fraught readymades with careful, contextualizing nuance. For her installation, a sound recording of a train—the line that carries the city’s manufactured goods across the border to the US—played intermittently, rattling the panels ominously, linking the area’s epidemic of missing and murdered women (many of them maquiladora workers) to labor conditions and trade.

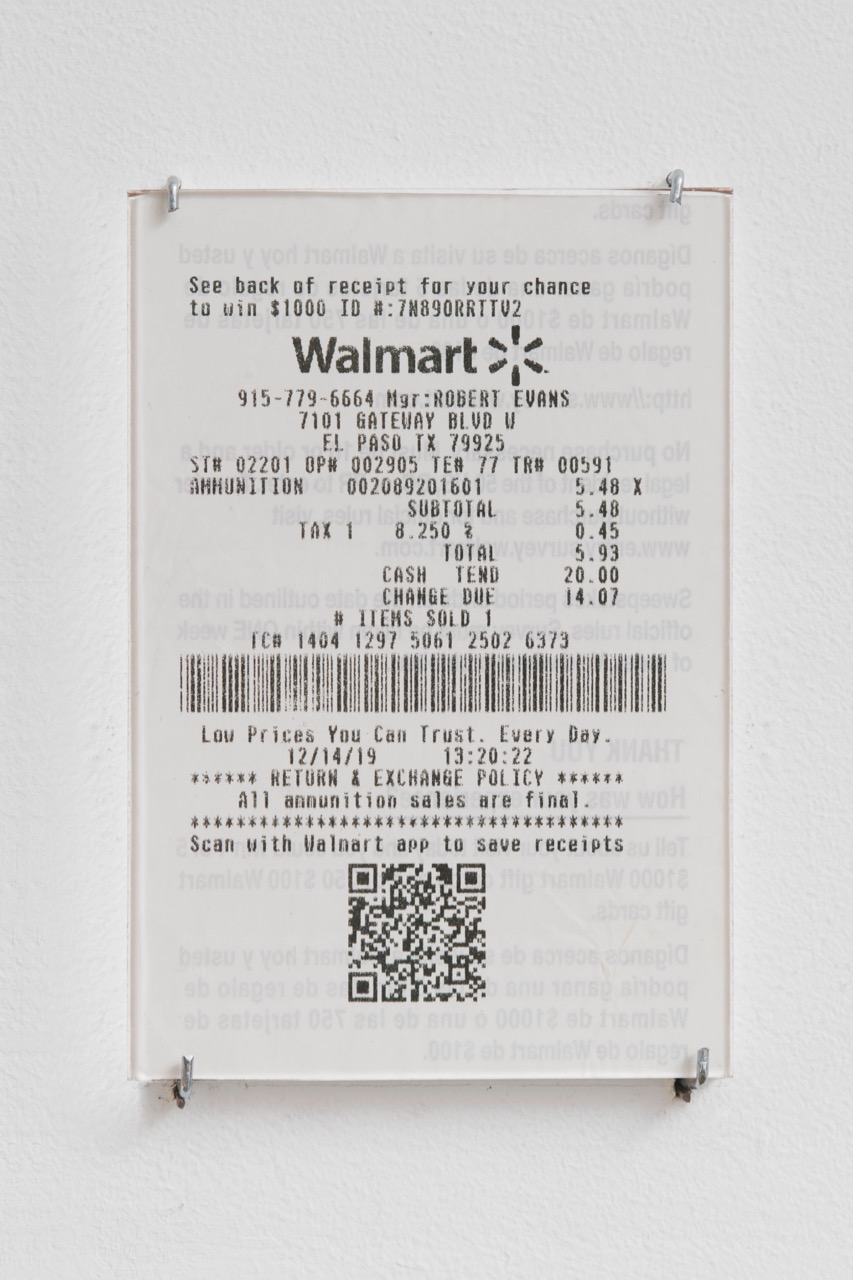

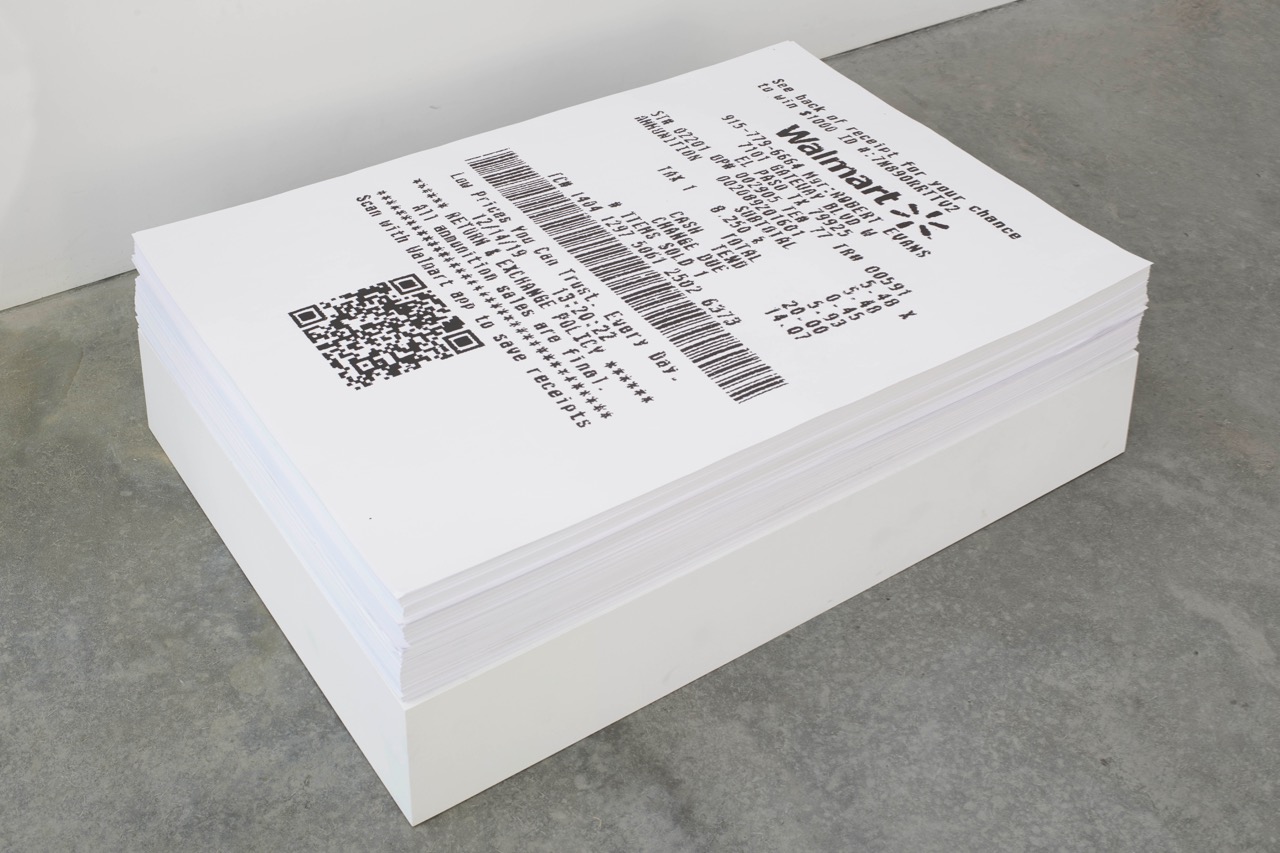

Teresa Margolles, Receipt, 2020. Receipt from purchase at Walmart, Gateway Blvd, El Paso, TX, 5 1/4 × 3 1/8 inches. © Teresa Margolles 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle.

Long focused on the crises of militarized cartels and femicide in Mexico, Margolles turns her eye to the scourge of mass killing in the United States with the first piece one encounters in El asesinato cambia el mundo. Placed near the gallery’s entrance, in the brightly lit reception area, Receipt (2020) stands as the exhibition’s visual and conceptual outlier. It seems to be a stark, ingenious homage to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Death by Gun) (1990). That piece, a stack of poster-sized prints (meant to be shown on the floor, and forever replenished), indexes, on each sheet, 460 US gun deaths from a single week in May 1989. For her stack of prints, Margolles enlarged a single receipt, for the purchase of a $5.48 box of ammunition from an El Paso, Texas, Walmart, to evoke the twenty-two people murdered there in little more than five minutes last August.

Teresa Margolles, Receipt, 2020. Stacked facsimiles of receipt from purchase at Walmart, Gateway, Blvd, El Paso, TX. © Teresa Margolles 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle.

The young white-supremacist suspect is believed to have posted an anti-immigrant manifesto about a “Hispanic invasion” just before the spree, in which he gunned down both Mexican and US citizens with an AK-47-style rifle. He would presumably have liked to kill both artists given the chance, but Margolles, though she has been to that superstore many times (it’s just across the border from Ciudad Juárez, where she often visits), wasn’t there. And Gonzalez-Torres (who was born in Cuba) has been dead since 1996, from AIDS-related illness—that is, from a case of government negligence to rival that of this country’s unconscionable failure to ban assault rifles. Receipt connects these dots, and others that bear upon the rest of the show: if far-right, racist conspiracy theories drive up gun and ammunition sales domestically, US manufacturers (and retailers at Southwest border states with lax gun laws) also profit from the firearms smuggled into Mexico for use by organized crime there. Those cartels are responsible for much of the violence referenced by, or embedded in, the exhibition’s following works.

Teresa Margolles: El asesinato cambia el mundo / Assassination changes the world, installation view. Pictured: El Brillo series. © Teresa Margolles 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle.

The next room is dimly lit. An atmosphere of sepulchral elegance sets the stage for Margolles’s new El Brillo series, a trio of velvet garments by unnamed, New York–based fashion designers. Each is hand-embroidered with a lattice or foliate motif incorporating jewel-like ornamentation—shards of glass gathered from, the checklist reads, “a site where violent acts occurred” in Culiacán, Cuidad Juárez, and El Paso, respectively. A glittering black shift could pass as contemporary sweatshop cocktail attire; a caped blouse and a kind of ornamental breastplate are, in contrast, vaguely Elizabethan, recalling a preindustrial mode of exploitation with their opulent, labor-intensive goldwork. Recriminating sorrow suffuses these luxury memento mori, skilled foils to the numinous heartbreak that comes after.

Teresa Margolles, El manto negro / The black shroud, 2020. Burnished ceramic pieces handmade by artisans in Mata Ortiz, Mexico, each approx. 4 1/8 × 4 3/8 × 1 3/8 inches. © Teresa Margolles 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle.

The show’s final installation, in the gallery’s main space, is a minimalist sanctum dominated by the wall-spanning El manto negro / The black shroud (2020), a dark grid composed of 2,300 ceramic squares. Margolles collaborated with a group of artisans from Mata Ortiz, Mexico—located in an area controlled by cartels, near the Paquimé archaeological zone in Casas Grandes—to make these subtly irregular forms from locally sourced clay. Each of the tiles, hand burnished to achieve its uniquely gleaming surface, represents and mourns a victim from the vicinity of the village.

Teresa Margolles, Dos bancos, 2020. Two benches made from a mixture of cement and material sourced from the ground where the body fell of a person shot dead at the northern Mexican border, each 19 3/4 × 17 3/4 × 55 1/8 inches. © Teresa Margolles 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan. Photo: Phoebe d’Heurle.

Two brutalist benches, placed so visitors might rest to contemplate the memorial, beckon. Fear or hesitation seem normal reactions to the checklist’s information that Dos bancos (2020), as the work is titled, is “made from a mixture of cement and material sourced from the ground where the body fell of a person shot dead at the northern Mexican border.” Yet—even if it were somehow possible for violence to infuse them with a chemical or psychic residue—such aversion is, Margolles implies, born of the delusion that a meaningful distinction can be drawn between the smooth gray material of the seating pressed against us, the pieces of El manto forged in despair, and the polished concrete floor of the gallery that completes the gleaming monochrome installation.

The artist’s uncommonly restrained sculptures owe their elegiac aura to our knowledge of their contact with tragedy, but, as if stoic in grief, they skillfully deflect our morbid curiosity about their particular, terrible provenances to raise the broader, crueler question—what in our world of contested territories, policed borders, institutional structures, private property, and consumer goods has not been likewise touched by or soaked with horror?

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.