Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

A Palme d’Or winner grinds the gears.

Agathe Rousselle as Alexia in Titane. Courtesy Neon. Photo: Carole Bethuel.

Titane, directed by Julia Ducournau, now in theaters

• • •

In Titane, a serial killer finds herself pregnant after fucking a car. On the lam, she pretends to be a long-missing little boy returning home as a young man and takes refuge with the child’s desperately credulous father. It’s a tantalizing premise to say the least, which, by virtue of its bold absurdity and engagement with deep kink, somehow drags the film across its grisly finish line, unassisted by a clear purpose or coherent plot. The French director Julia Ducournau, who won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this past July for Titane (only the second time in the festival’s seventy-five-year history that the top prize has gone to a woman), presents a sequence of violent events, a few motifs, and a shaky character arc or two. And while the film is visually transfixing in moments and sometimes in stretches, its most intriguingly outlandish storyline—namely the conception and gestation of a car fetus—turns out to be oddly gratuitous.

An auto show is the lurid, carnivalesque setting for an early scene that introduces the protagonist Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) dancing on and around a flame-emblazoned Cadillac. Lissome and surly in gold spandex and neon fishnets, she deploys a raunchy hostility in place of flirtation. After work, in a desolate parking lot, she draws an obsessed fan close, rolling down her car window to make out with him from her position in the driver’s seat, then letting her hair down to stab him through the ear, using a well-practiced move with her weapon of choice—the spike-like pin that fastens her messy bun. It comes as no surprise when a news broadcast reveals that she’s responsible for a spate of murders.

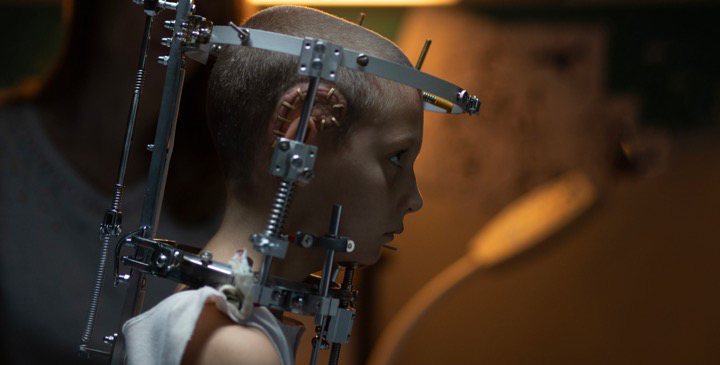

Adèle Guigue as Alexia at seven years old in Titane. Courtesy Neon.

Her motivation is mysterious throughout the film, even though, in Titane’s opening segment, we get her origin story. As a child of seven, she’s riding in the back of her father’s car, kicking his seat with a scowling fury as he drives. Losing his temper, he turns to yell at her, and they’re in a terrible collision. When little Alexia, her skull patched with a plate of titanium (hence the film’s title), leaves the hospital with her parents, she immediately begins to stroke and kiss a car like a cyborg Bad Seed. Whether metallurgic or pseudo-psychoanalytic or both, there is an explanation of sorts here for her automobile fetish and pronounced so-called daddy issues—but why is she a serial killer? Why not, I guess.

Ducournau is indebted to David Cronenberg in many respects, and much of the imagery in Titane echoes the explicit portrayals of sex and arousal in his 1996 adaptation of J. G. Ballard’s 1973 novel Crash, whose subjects get off on car accidents. The similarities between Cronenberg’s then-controversial, precisely constructed, dystopian commentary and Ducournau’s comment-less supernatural-sci-fi mess perhaps end with their eroticization of machines, though. Curiously, Titane is almost shy about sex when compared to Crash. During Alexia’s trysts with cars, she’s shown upright in the back seat, gripping opposite shoulder belts, her wrists wrapped as though in restraints. Everything below the waist is left to the imagination. After the first such encounter, we see the crotch of her underwear stained with black grease, but the mechanics of this implied penetration are never disclosed. I can’t decide if this omission is wise or if it’s a cop-out, an evasion of the hard pornographic truth of Alexia’s representation. Ducournau’s initial hypersexualization of her protagonist is never successfully undone—not by miserable circumstances, a shaved head, or different clothing. The film betrays its own ostensible ambitions, retreating into tired body-horror tropes at every point where Alexia might become more than a female droid programmed to fuck, kill, and self-destruct.

Agathe Rousselle as Alexia in Titane. Courtesy Neon. Photo: Carole Bethuel.

This is not to say she does not change at all. There is a surface transformation, from predatory showgirl to gravid boy to monster in extremis, and a psychological downshifting from indiscriminate terminator to human sociopath. Alexia eventually begins to develop a limited emotional range after an exhausting murder spree in which a tense lesbian hookup leads to a house-party massacre and then the incineration of her parents’ home. Now a fugitive (there’s a surviving witness to describe her), Alexia spots a computer-generated age projection of a missing boy named Adrien and brutally modifies herself to resemble the young man he might have become. Adrien’s father, Vincent (Vincent Lindon), a hunky fire chief of a certain age, shows not a flicker of disbelief when he sees this beat-up, sullen impersonator. He ignores the skepticism of the police and then the warnings of everyone else in his life.

Vincent Lindon as Vincent in Titane. Courtesy Neon. Photo: Carole Bethuel.

Really the story from here on is not about Alexia or her alarming, expanding abdomen, which she binds flat with dirty bandages and scratches frantically, tearing her skin to expose black patches of oil. It’s about Vincent and his Christlike devotion to a violent stranger who cruelly pantomimes the role of his almost surely dead son. For Vincent, who probably deep down knows the truth from the start, love is thicker than blood, and it grows stronger each time it’s tested.

When, early in their relationship, Alexia attempts to kill him, he wrestles her hairpin away, fighting for his life, then confiscates it like a toy from a misbehaving child. She is silent, blank, mostly uncompliant, but he insists she work alongside him and his crew of firefighters. Later, amid a small, orgiastic firehouse rave, she disturbs the party’s ultramasculine homoerotic equilibrium by commanding the spotlight while atop a fire truck, and dancing—as Adrien—with the feminine menace she exuded in the car-show scene. When Vincent walks in on the spectacle, it gives him pause—maybe because he’s homophobic, maybe because he knows that this father-son farce is almost up.

Vincent Lindon as Vincent in Titane. Courtesy Neon. Photo: Carole Bethuel.

Lest you get the impression from such scenes that this allegedly shocking, fêted film has something interesting to say about gender, sex, or sexuality, I should clarify that it does not: while much of Titane’s subject matter provides obvious openings to explore the mutability of anatomy and identity, queerness, transness, sex work, fetishism, and the degendering of reproduction (for example), none of these topics are explored with any depth or nuance if they are acknowledged at all.

Potentially pivotal moments of shattering physical pain, events that you might reasonably expect to push Alexia into novel psychic terrain—when she attempts an abortion with her murder pin, when she breaks her own nose on a bathroom sink to resemble Adrien—are played as gruesome one-liners. And Ducournau’s bid to depict something like “fluidity,” between her botched portrayals of dysphoric despair, ultimately serves only to reinscribe Alexia as a cis psycho doomed by sex, evinced by her abject gender reveal and excruciating birth scene at the end. For a story that contends with a sexuality baptized by traumatic injury and a body pushed to its limit by punishing metamorphoses, Titane’s studious inattention to its own implications is rather remarkable. Despite its absorbing flash and gore, and its deceptive air of considered complexity, it collapses under scrutiny the minute the credits rolls—or before.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.