Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Not all is quiet on the American-art front.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, installation view. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Pictured, left to right: Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion, 2023; Julia Phillips, Mediator, 2020; Harmony Hammond, Patched, 2022; Harmony Hammond, Black Cross II, 2020–21; Harmony Hammond, Chenille #11, 2020–21.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, co-organized by Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through August 11, 2024

• • •

Without the catnip of Biennials past—flashy provocations time-stamped by pop-cultural references, breathlessly installed sequences of work, or protests—the eighty-first edition, co-organized by Whitney curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli, comes off as a little subdued. Critical consensus seems to skew thumbs-down for Even Better Than the Real Thing, with many noting its air of restraint as a negative. But understated feats, whose effects are often of the time-release variety, can be mistaken for lackluster gestures when the two are intermingled in an uneven, overhyped exhibition (which is every Biennial, really). Or perhaps the standouts get a little lost when everything on view is equally overshadowed by an elephant in the room.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, installation view. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Pictured: Ser Serpas, taken through back entrances subtle fate matching matte thing soiled . . ., 2024.

This year, the show, traditionally an arena for political confrontation, opened to a moment of particularly bitter divide—with Gaza at the brink of starvation, and every major American art institution at its wit’s end, it seems, scrambling to contain the speech of the cease-fire majority. It makes sense, then, that a museum would give little indication of what’s really going on, but in a Biennial that otherwise does not shy from political statements, it’s chilling to have to read between the lines.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, installation view. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ashley Reese. Pictured: Isaac Julien, Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die), 2022.

Contributing to the sense of quiet, the main galleries feature forty-two artists (fewer than usual), whose work is installed in a straightforward manner, whether isolated so that no conversation is forced, or placed in gently synergistic arrangements—a world away from, for example, the buzzing energy of 2022’s open-plan tag-sale arrangement on the fifth floor. In contrast, 2024 feels like a careful, critical rightsizing of the storied exhibition and its claims. For all of the show’s legendary clout and aspirations to breadth, it’s never been a true cross section; it’s always been marred by egregious exclusions. This time, rather than pretending to present a panoramic snapshot of contemporary art, the curators have mounted a diffuse (occasionally pointed) response—not to the last two years, but to an institutional tradition and an era. They dispense with the notion of “diversity” advanced by recent Biennials—as something measured by a demographic head count—in favor of a broader, long-game rebalancing and decentering. As the press materials explain, in addressing a climate of transphobia, ongoing assaults on bodily autonomy, and “a long history of deeming people of marginalized race, gender, and ability as subhuman—less than real,” the curators have focused, almost exclusively, on the work of these groups. Good—it’s a vast, varied pool to draw from. There’s no shortage of great things here.

Suzanne Jackson, Rag-to-Wobble, 2020. Acrylic, cotton paint cloth, and vintage dress hangers, 91 1/2 × 54 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Ortuzar Projects. Photo: David Kaminsky.

On the sixth floor, Suzanne Jackson and Harmony Hammond, both Biennial first-timers born in 1944, demonstrate the oblique radicalism of abstract painting at its very best—Jackson with an airy garden of hanging compositions, like multicolor curtains or carapaces of hardened gel medium, embedded with netting, shredded mail, and clothing hangers; Hammond with her weathered, punctured, patched canvases, including a tattered version of a Malevichian black cross. The pair are represented by recent works, but they have long labored to highlight the allusive, gendered qualities and cultural, craft references of their materials. They’ve also acted behind the scenes, laying the groundwork for alternative art worlds and movements. In the late 1960s, Jackson opened Gallery 32, an experimental space in Los Angeles devoted to the work of Black artists; in the 1970s, Hammond was an organizer of lesbian group exhibitions and a founder of the feminist gallery A.I.R as well as Heresies magazine.

Mary Kelly, Lacunae, 2023 (detail). Ragboard, vellum, ash, and ink; ten framed panels, 38 1/2 × 24 × 1 3/4 inches each. Courtesy the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Panic Studio Los Angeles. © Mary Kelly.

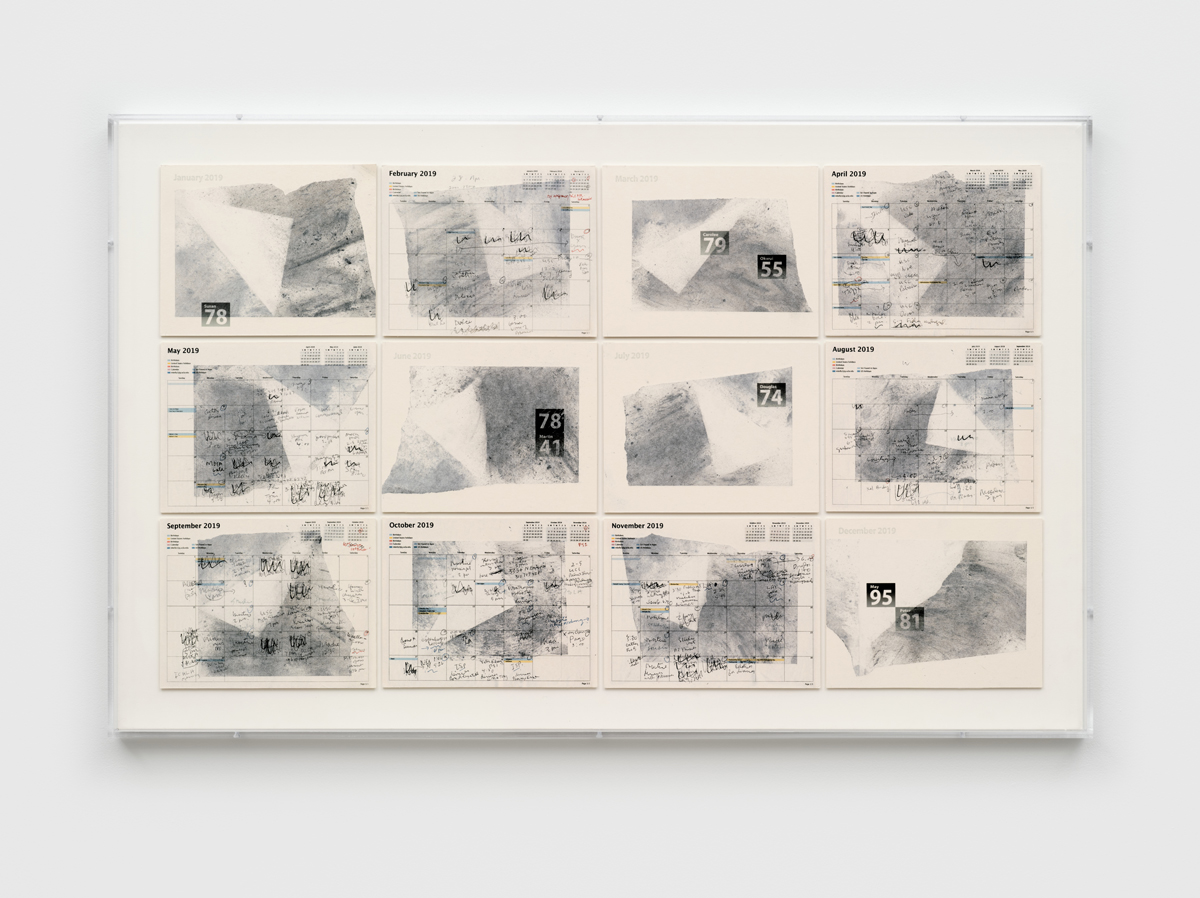

While these artists’ evocations of flesh provide a foil to the technologically mediated, deconstructive approaches to the body of younger generations (such as the 3D-printed CAT-scan assemblages by Jes Fan and the stark, fragmented figurative sculptures by Julia Phillips), a piece of subtle power by Mary Kelly, born in 1941, stands as a precursor to the show’s thread of more conceptual endeavors. Lacunae (2023) is a grid of calendar pages, annotated and rubbed with ash to mark the deaths of friends over the course of a decade, its form hearkening back to Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973–79), a landmark of feminist rigor and the women’s art movement, which dispassionately tracked the growth of her son. In the same room, Sharon Hayes—once a student of Kelly’s—invites viewers to pull up a chair, as though to join her filmed conversation between queer and trans elders, and Carolyn Lazard—once a student of Hayes’s—shows a miniature hall of mirrors, a Minimalism-spoofing maze of Vaseline-filled bathroom cabinets, fraught with domestic and bodily associations. In a different gallery, Carmen Winant, whose work calls back to both Kelly’s indexical approach and her unlauded subject matter, shows The last safe abortion (2023). Winant has filled a wall with a kaleidoscopic grid of 2,700 archival photographs, a Herculean paean to clinics and their workers, and a meticulous mourning of a human right.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, installation view. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Nora Gomez-Strauss. Pictured, foreground: Charisse Pearlina Weston, un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), 2024. Back wall: Mavis Pusey, Within Manhattan, 1977.

Another intergenerational encounter, whose connection is more visual and associative, is staged on the fifth floor. A dramatic architectural intervention, a transparent, angled canopy—like a menacing “glass ceiling”—by Charisse Pearlina Weston, born in 1988, echoes the hard-edge diagonals of an adjacent suite of towering, knockout paintings from the 1960s and ’70s by Mavis Pusey, a Jamaican-born abstractionist who died in 2019 at age ninety without the recognition she deserved. (A wall label notes she was included in a Whitney exhibition of Black artists in 1971, which artists protested for its white curatorial perspective.)

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, installation view. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Audrey Wang. Pictured: Diane Severin Nguyen, In Her Time (Iris’s Version), 2023–24.

Other highlights include a breathtaking, sexy five-screen video installation by Isaac Julien, a dreamy exploration of African art and Black modernism centered on Alain Locke (played by André Holland); the melding of figure and verdant landscape in a performance-video by the South American Indigenous Mapuche artist Seba Calfuqueo; and Ser Serpas’s ground-floor installation, composed of locally street-scavenged materials (scattered Mylar birthday balloons, disassembled furniture, a shard of mirror), which exudes an edgy, improvisatory joie de vivre—a welcome register of volatility mostly absent from the show. Another tonal outlier is Diane Severin Nguyen’s captivating film, a hallucinatory narrative fiction in which a young actress prepares for a role in a movie about the Nanjing Massacre. Its sixty-seven minutes of rehearsals, role reversals, and lush artificial gore are strangely affecting in a time when real images of atrocity are devastatingly or numbingly abundant.

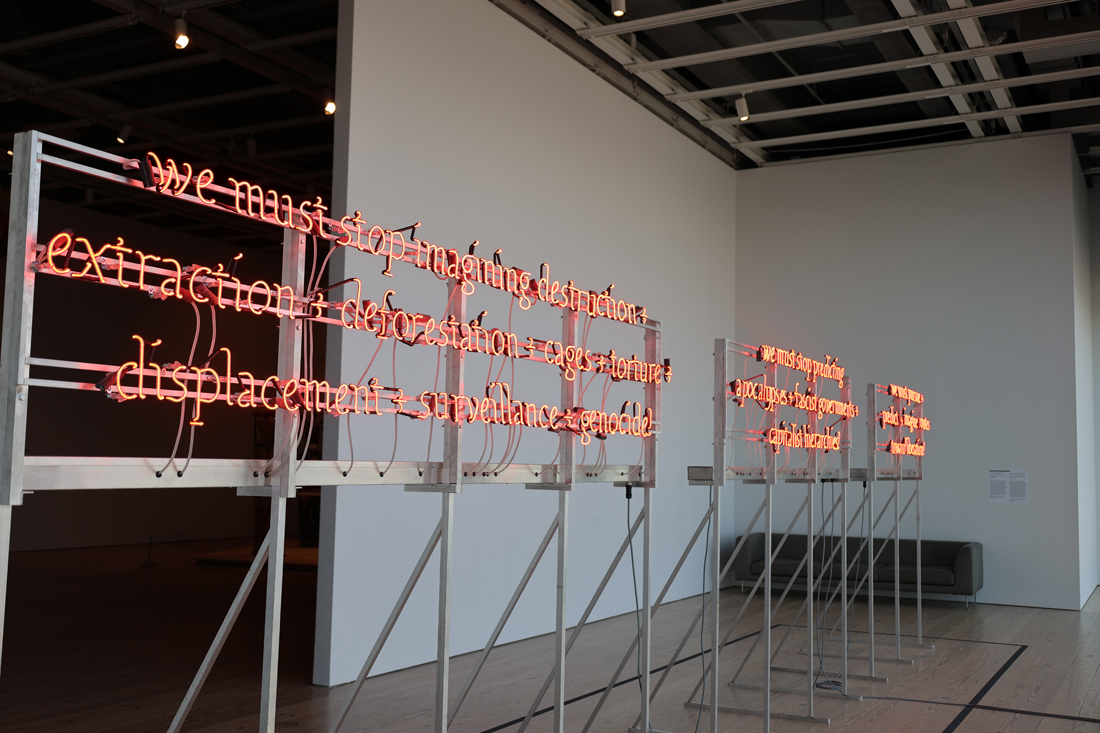

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing, installation view. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Nora Gomez-Strauss. Pictured: Demian DinéYazhi ́, we must stop imaging apocalypse / genocide + we must imagine liberation, 2024.

And as you may have heard—it was in the news—the silence on Gaza was broken, just barely, by a surprise message. It was discovered (after the press preview) that the neon text piece overlooking the Hudson from the fifth floor—an earnest poem by Demian DinéYazhi’ titled we must stop imagining apocalypse / genocide + we must imagine liberation—also spells out “free palestine” in sporadically blinking letters. I wasn’t impressed by the illuminated polemic initially, but when I returned to the show, I saw that the artist had achieved something crucial. Headlines speak louder than wall labels: museumgoers huddled in the red glow, trying to make out the slogan. By suggesting, or revealing, that such a sentiment could not be expressed openly—that it must be snuck in—DinéYazhi’ says everything about the current climate. And, in the poem’s shift from generalized language to the urgent specificity of its “hidden” demand, it thwarts comfortable readings of the Biennial’s other inclusions—or of the Biennial as a whole— which might otherwise be too easily consumed by those who take their liberation struggles à la carte.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and musician in New York.