Rhoda Feng

Rhoda Feng

All the world’s a stage for the first Chinese woman in America.

Shannon Tyo as Afong Moy in The Chinese Lady. Photo: Joan Marcus.

The Chinese Lady, by Lloyd Suh, directed by Ralph B. Peña, the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette Street, New York City, through April 10, 2022

• • •

The first thing you notice about The Chinese Lady (directed by Ralph B. Peña at the Public Theater) is the imposing storage chest that encloses the stage, one wall of which has been replaced by a curtain that pulls back to reveal the life-size diorama in its interior. It turns out to be something like a colossal cabinet of curiosities. Set designer Junghyun Georgia Lee has furnished the room to look like a docent’s idea of a Chinese saloon, replete with vases, curtains, silks, and other works of chinoiserie. The central “curiosity,” though, is Afong Moy: the first Chinese woman to arrive in America, a historical personage, played here by Shannon Tyo—winsomely, at first, then lugubriously.

In the opening scene, the year is 1834, and a fourteen-year-old Moy—who possesses a slightly suspicious maturity beyond her years—starts introducing herself with a well-rehearsed litany of biographical facts . . . then goes on to reintroduce herself throughout the play, each time a little older. She pays sedulous attention to her early Victorian–era spectators—er, that would be us. “I understand it is my duty to show you things that are exotic, and foreign, and unusual,” she says at the outset. Cue nervous laughter from the audience. On the night I attended the production, those seated around me were mostly white—a demographic that would not have looked so different, one imagines, from the one that paid 25 cents to see Moy.

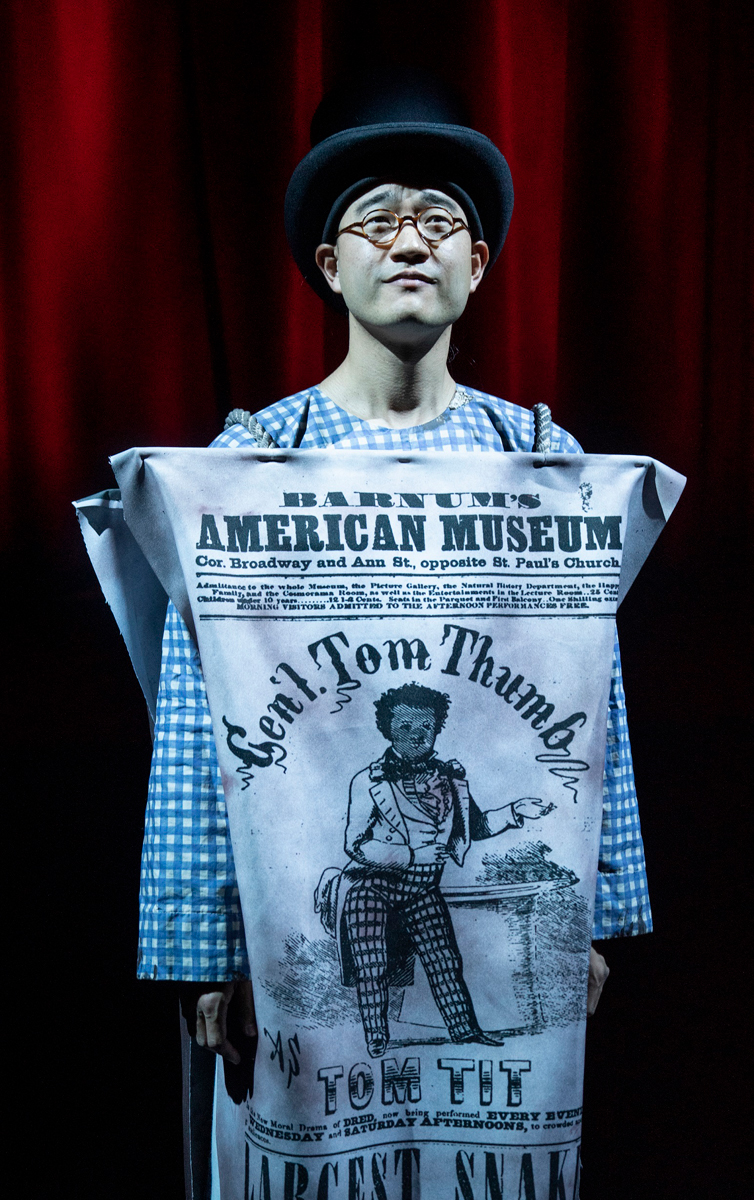

Daniel K. Isaac in The Chinese Lady. Photo: Joan Marcus.

For all the poetic liberties it will take, the play maintains a kite line to the historical record. (I say this advisedly; we do not know a great deal about the real Moy, and much of what we do know comes fifth-hand. As one character reflects, “She is like a wisp, a memory, an idea, a poem.”) As in the play, Moy, who was born in Guangzhou Province, was sold by her father in 1834 to two brothers—Frederick and Nathaniel Carnes, of Salem, Massachusetts—as part of a ploy to market Eastern wares to Americans via an exoticized fantasy of China. They exhibit her as a “curiosity” in Philadelphia’s Peale’s Museum for the delight and edification of its visitors. Theatrical impresario P. T. Barnum would take custodianship of her in 1847, billing her as the “only Chinese Lady that ever left the walls of Canton.” At the height of her iconicity, she drew up to two hundred visitors a day.

Shannon Tyo as Afong Moy in The Chinese Lady. Photo: Joan Marcus.

We see her, for the first half of The Chinese Lady, at Peale’s Museum, performing eating (or, more precisely, picking at her meals) with chopsticks, pouring tea “in a ritualistic way so as to demonstrate its importance in my culture,” and walking about the room to show off her bound feet. Splayed on the page, many of Moy’s musings resemble poetry. As performed by Tyo, however, her lyricism comes through more in her movements than in her soliloquies, which are feats of animated asyndeton. Moy speaks flawless American English throughout, but also explicitly tells the audience “this is not in fact what is happening”—we’re meant to believe she has no knowledge of the language. (This play likes to have things both ways.) Hence, the need for an interpreter. Seated invariably within earshot is Atung (Daniel K. Isaac), an older Chinese man who frostily translates questions from imaginary spectators for Moy’s benefit.

Daniel K. Isaac as Atung in The Chinese Lady. Photo: Joan Marcus.

By Moy’s second or third prelude, we have picked up on certain pressure points and learned to listen for what she elides, papers over, or contradicts when talking about herself. No two versions of Moy are identical, and the differences can speak volumes. In her parade of preambles, she exhibits a curious kind of double vision—one that generates a running commentary on her current situation and often alludes to future events she could not plausibly know about. Whose voice are we hearing, for instance, when the now-seventeen-year-old holds forth on the nascent Opium Wars of the 1840s? She admits to being “shielded from news of the world” as an adolescent and adds: “I do not know that I do not know this, either.” In moments like this, she becomes less a flesh-and-blood girl, more an emissary from the future. “All I know is that you are looking at me, that I am presenting this image, that I have so much hope and so little reality,” she intones. “With each passing hour I am less and less Chinese.”

Shannon Tyo as Afong Moy in The Chinese Lady. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Moy’s popularity with the museum crowd means that she ends up staying in the US beyond the two years originally projected by her handlers when they bought her. A budding entrepreneur, she dreams of returning to China with an American girl, who would be exhibited as a curiosity, sleeping on a raised mattress, wearing shoes at home, and eating with a fork. Moy’s vision doesn’t come to pass, and her story moves toward a bleak conclusion that feels somewhat predictable. With the Carnes brothers, she manages a few more tours in other cities—including Providence, Pittsburgh, Boston, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and Washington, DC, where she meets President Jackson (who has a thing for bound feet)—before her peripatetic life catches up with her. Fifteen years after we first met her, Moy is no longer the impressionable, eager-to-please ingenue. She goes increasingly off-piste in her speeches, is overcome by ennui, and imbibes whiskey instead of tea. At age twenty-nine, having spent over half her life on display, she decides to give up the act and head West, “in search of more Chinese in America.”

Shannon Tyo as Afong Moy in The Chinese Lady. Photo: Joan Marcus.

This is where the play ought to have ended—on a note of open-ended possibility. Instead, with two more scenes to go, it takes a turn for the worse. When we see her next, Moy is middle-aged and has exchanged her traditional Chinese costume for jeans and a loose-fitting sleeveless shirt, ostensibly to telegraph that she is now our contemporary. Yet an extradiegetic quality still enshrouds her. It’s as if she exists just beyond the rim of the current moment, trapped in a no-man’s-land between being seen and self-seeing, between chimera and consciousness. Moy launches into a discourse on the “subject of gold . . . [and] Liberty,” racial discrimination, and the need for “a platform for understanding, for learning, for sharing.” One can almost see the lawn signs, rendered in all caps: “In this house, we believe in safe spaces.” This section veers into didacticism while lamentably lacking the conviction or unorthodoxy of anything like a Brechtian “learning play.” It also relies on extensive relays between the past and future, linking episodes when anti-Asian sentiments have engulfed American society.

Moy is gouged by guilt; she thinks that if she had been a better cultural ambassador—“if I had walked differently. Eaten differently, provided more clarity on the metaphysical metaphor of tea”—then maybe Chinese American workers would never have been decapitated and castrated, tortured and drowned. The walls of the storage cabinet are transformed into a projection screen for headlines announcing such atrocities. This all feels somewhat ham-fisted; playwright Lloyd Suh is so intent on adjusting the moral hemlines of his characters that he obscures their other particularities. Grief, or rather, the performance of grief, is monumentalized. As Moy opines on events even further calendrically removed from her life, like the Civil War, Lincoln’s delivery of the Gettysburg Address, and the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, she starts to sound like a depersonalized conduit for transhistorical ideas. In the final moments, Moy entreats the audience to “look at each other” as large pairs of Asian eyes stare out at us from the walls on stage. And then she’s gone.

Rhoda Feng is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC.