Rhoda Feng

Rhoda Feng

A stage adaptation by Elevator Repair Service brings a madcap energy to James Joyce’s notoriously difficult novel.

Cast of Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Ulysses, created by Elevator Repair Service, text by James Joyce, codirection and dramaturgy by Scott Shepherd, directed by John Collins, the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette Street, New York City,

through March 1, 2026

• • •

Dora García’s 2013 documentary The Joycean Society features as amiable a gathering of James Joyce enthusiasts as one is likely to encounter. In a book-lined room, a small cohort of bibliophiles sit behind two rows of white desks as they puzzle over a few inches of Finnegan’s Wake. Paging through pages petaled with Post-its, the members ruminate over the intricacies of Joyce’s cryptically allusive final work; they discuss its lexical playfulness, Freudian references, nursery rhymes, and etymologies of names. “It’s extraordinary,” one participant observes. “This is a book where you could take out very many passages or words—paragraphs or words—and it wouldn’t make much difference to our reading of it.”

Scott Shepherd as Buck Mulligan in Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Taking out very many paragraphs and words is exactly what Elevator Repair Service (ERS) has done with its stage adaptation of Joyce’s other notoriously difficult novel. Its Ulysses, which intermittently gives a whiff of a genially combative reading group, starts with a disclaimer. A professorially rumpled Scott Shepherd, who codirects and stars in the show, stands before a bank of conference tables and offers a few orienting remarks about Joyce’s modernist masterwork and this nearly three-hour adaptation. It is “in the interest of continuing the confusion and controversy that Joyce evidently intended to be part of our experience,” he ventures, that ERS has devised this work (an earlier version premiered at the Fisher Center at Bard in summer 2024). He also alerts us to an analog clock mounted on the back wall, which will mark the hours of this day—June 16, 1904—in which “not much happens.” “Mark” proves to be an elastic term: the clock does not simply tick metronomically forward: at certain junctures, its hands windmill ahead or knife backward to approximate Joyce’s own temporal cues.

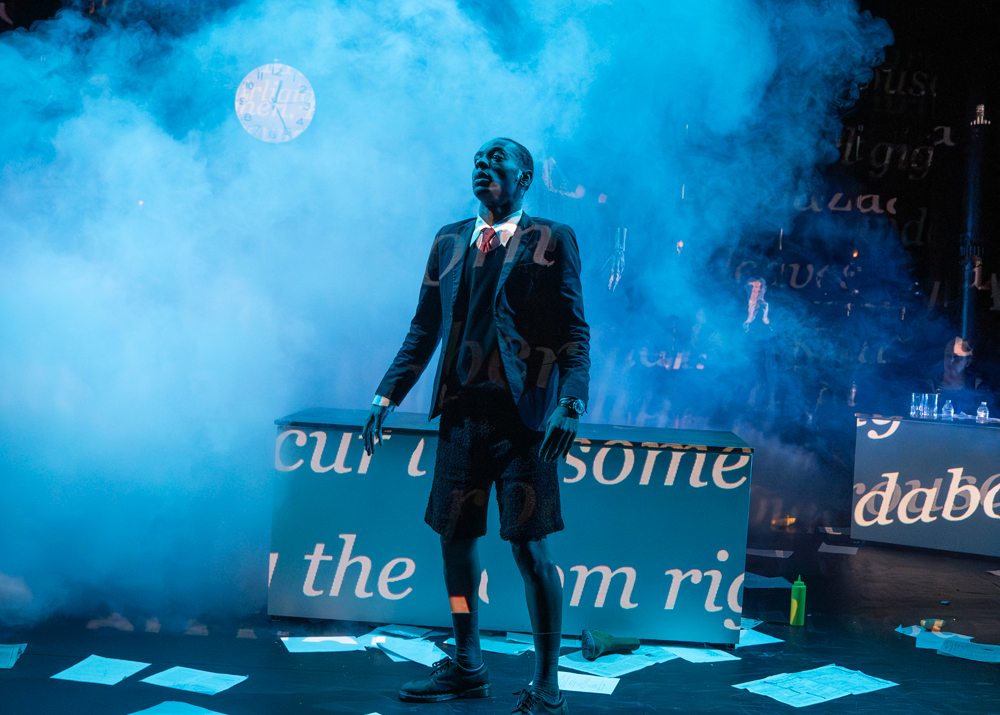

Cast of Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Post preliminaries, Shepherd and six other actors take their seats behind the tables. Stiff of posture, the septet resembles a group of subpoenaed witnesses. (The literary panel–like scenic design is by the dots collective.) A woman (Stephanie Weeks) at the far left begins reading, in a voice as clear as a bell, the opening paragraph from a blue-bound copy of Joyce’s novel. The next ball to rise is “stately, plump” Buck Mulligan (Shepherd) intoning the opening phrase of the Mass. Then a sullen-faced Stephen Dedalus (Christopher-Rashee Stevenson) thinks ruefully of his late mother, whose fearful aspect recently appeared to him in a dream. His morbid thoughts are interrupted by Mulligan, who floats the idea that “Hamlet’s grandson is Shakespeare’s grandfather and that he himself is the ghost of his own father.” Crickets. It seems no one else has done the reading. Yet eight episodes later, we find Stephen’s thoughts orbiting the melancholy Dane. Who can say how much time has passed between “Telemachus” and “Scylla and Charybdis.” Clock time says one thing (four hours); phone time says another (fifty minutes); the half-dozing man to my right suggests yet another.

Christopher-Rashee Stevenson as Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Unlike Gatz, ERS’s love-it-or-hate-it word-for-word traversal of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, this Ulysses wisely does not attempt to compete with marathon readings of the novel. A Pangaea of prose is missing from the script—about 92 percent. Yet, all the cut words appear (allegedly) onstage in the form of projections, designed by Matthew Deinhart. Not that you’ll be able to read what’s beamed, at regular intervals, on the sides of the desks facing the audience and upon the back wall: the lines scroll upward at 10x speed, sometimes even faster, as if suffering an attack of the bends. It’s a method of encounter that might give one pause. What could be more at odds with a text that, with its fragmentary clusters and serpentine sentences, insists on being tarried over? “Drunks cover distance double quick,” one character thinks to himself. (During intermission, one woman behind me muttered, “I think I’ve seen enough,” before heading out with her companion. Perhaps she thought the play was too drunk—or possibly not drunk enough.) Occasionally, as in a scene set in a newspaper office, the madcap energy threatens to coalesce into a bibulous canter through Joyce’s famously “unmortared” prose. Alternatively, a more diluted or dilatory production might have taken a more Aeolean route, puffing from passage to julienned passage, memory to memory at exasperating length. As codirectors, Shepherd and John Collins rein in this latter impulse. If discrete parts of Ulysses can be likened to vast, billowing tarps of consciousness, ERS manages the impressive feat of keeping them from lifting clear off the ground by bolting them down with the sturdy pegs of “he said” and “she said.” (Weeks and castmate Dee Beasnael supply much of the narration.) Myriad props (by Patricia Marjorie) that enter the lives of Stephen and Leopold Bloom (Vin Knight), adman about town, also tether the production to domestic details of Dublin life.

Cast of Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Maud Ellmann wrote that Ulysses transforms “epic into body, and body into epic, through the use of language that enacts organic processes . . . When Bloom eats his lunch, the language ruminates or chews its cud; when he masturbates, the language tumesces and detumesces; when he visits the brothel, the language is convulsed with . . . the spastic spasms of tertiary syphilis.” Even if this ERS production never achieves the syphilitic spasms of the section known as “Circe,” it does, especially in its second half, succeed in creating distinct enough tempos that we come to feel each episode to be governed by its own internal clock. Nothing in the sober-minded opening prepares you for a phantasmagoric scene in which Bloom, draped in an ermine-lined crimson mantle, presides over the construction of a “New Bloomusalem” and gives birth to octuplets.

Scott Shepherd as Buck Mulligan and Vin Knight as Leopold Bloom in Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

There is a distinct sense of the show moving vascularly from the brain to the heart to the loins, with much of the middle taken over by digestion. Leopold Bloom’s hale and hearty appetite is foregrounded in several food-forward scenes. A potato in Poldy’s pocket is a punctum that turns up repeatedly and there’s a funny scene involving large plates of cabbage, which the cast members lustily devour. Food also shows up in unlikely situations: when Bloom is examined by a team of sexologists—he’s declared “a finished example of the new womanly man”—he rests his head on a sandwich rather than a pillow. The Vaseline that Bloom offers Blazes Boylan (Shepherd, limbs ajingle), his usurper in the marital bed, is squirted from a bottle of mustard. ERS’s adaptation of the play, which samples from every chapter of the novel, itself resembles a delectable tasting menu: this should entice rather than discourage Ulysses novices. For those more acquainted with the novel, the play works a different kind of magic: its dialogue-heavy lines serve as a contrast dye for the novel’s opaque nervous system.

Maggie Hoffman as Molly Bloom in Ulysses. Courtesy the Public Theater. Photo: Joan Marcus.

The show rounds the horn of nostos, or the return, at a quarter to two in the morning. Scrunched up in bed beside her husband’s cold feet, Molly (Maggie Hoffman) begins her famous soliloquy, naveling inward and onward for nearly thirty minutes before she’s joined by a chorus of other women. Collectively, they give voice to the swirling Esperanto of her mind. And yes, I was mesmerized and inched forward listening to Molly deliver her lines, each thought scored like a psalm, yes, each turn precisely articulated and that was what a mind speaking to itself sounded like, yes, its own universe, or a dot in the universe, like that wink of ink at Ithaca’s end that only looks to be stalling and is more like an opening or an oubliette to what, I wondered, or to who and egressing digressing I wonder still.

Rhoda Feng is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC.