Ciarán Finlayson

Ciarán Finlayson

From family to Flint to factory workers: photography focused on movements of solidarity.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, organized by Roxana Marcoci with Caitlin Ryan and Antoinette Roberts, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through September 7, 2024

• • •

Gabriel Winant’s book The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America begins with a sinister occlusion: eleven years ago, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UMPC), the largest private employer in Pennsylvania, claimed to the National Labor Relations Board that it “has no employees.” This disappearing of workers from the scene of outstanding profits is the project which the Braddock-born photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier has devoted herself to revealing. In her breakout series The Notion of Family (2001–14), UMPC pulls all aspects of the artist’s life into its orbit. The hospital conglomerate is a site of care for her grandmother Ruby and step-great-grandfather Gramps; of employment for her mother Cynthia, who worked as a nursing assistant; and of “a community center / a cafeteria and restaurant,” per one of the artist’s poetic captions. Frazier began the series when she was nineteen years old and concluded it at age thirty-two.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and Me from The Notion of Family, 2005. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery. © LaToya Ruby Frazier.

The Notion of Family occupies the first two galleries of Monuments of Solidarity, Frazier’s mid-career survey at the Museum of Modern Art, which features two-and-a-half decades of her practice across photography, video, and installation, arranged here as “monuments for workers’ thoughts.” The category of worker is elastic—in The Notion of Family, it was the artist-as-proletarian-photographer documenting her own community as the devastation of industrial collapse was being “translated,” per Winant, “into the form of health problems.” Frazier works in the social documentary tradition, but she is neither Jacob Riis nor Berenice Abbott. Because she is socially proximate to her subjects, she’s able to operate at a further remove, introducing needed elements of irony. There’s a capsule history of photography here in the opening rooms, where you can see Frazier citing James Van Der Zee, Carrie Mae Weems, and Diane Arbus. It’s the attention to drama and the mundane grotesque that sets these scenes apart: Grandma Ruby Wiping Gramps is Frazier as Dorothea Lange as Larry Clark.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured, far right: Shea Cobb Going to Vote at Doyle-Ryder Elementary School, Flint, Michigan, 2019.

Her second major series, Flint is Family in Three Acts (2016–20), follows poet and bus driver Shea Cobb and her mother, daughter, and closest friend and collaborator as they all navigate the toxic water event. In Self-Portrait with Shea and her Daughter Zion in the Bedroom Mirror, Newton, Mississippi (2017–19), the daughter stares into the mirror; the mother stares at the daughter; the artist’s camera catches the subjects, their mirror representations, and its own reflection among the stained wallpaper, popcorn ceiling, and jagged mirror resting on a towel that turns a set of plastic bins into a makeshift dresser—all framing Shea’s determined grit. The picture most explicitly calls back to Mom Relaxing My Hair (2005) from The Notion of Family, plotting Frazier in the Cobb-family nexus.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured: More Than Conquerors: A Monument For Community Health Workers Of Baltimore, Maryland 2021–2022, 2022.

The second half of the show is defined by pairings of photos and text. Frazier is now less a family member than someone in solidarity with and in service to her subjects. She profiles community health workers in Baltimore after peak COVID; documents the last nine months leading up to the idling of the General Motors complex in Lordstown, Ohio; and pays homage to United Farm Workers cofounder Dolores Huerta. Here there are Operation Desert Storm vets, Gulf War militants, corrections officers, whistleblowers, literary magazine editors, pastors, and accountants in tender and tidy images that are not meant to arouse sympathy. Frazier is actively leveraging her art-celebrity status to present these subjects both as they want to be seen—upright, self-sufficient, dignified—and as an intensely heterogenous group that nevertheless acts as a unit.

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured: The Last Cruze, 2019.

To make The Last Cruze (2019), Frazier visited the United Auto Workers Locals 1112 and 1714 multiple days each week for nine months. She was granted their unanimous permission to document the famous Lordstown plant—the location of an epochal rank-and-file rebellion against speedups on the assembly line in 1972—in the run-up to its being illegally idled (“unallocated”). What began as a commission for the New York Times Magazine expanded to an intensive series of more than sixty portraits, landscapes, and protest scenes presented with detailed interviews with the workers and their families. These configurations of texts and gelatin silver prints, usually presented in sets of three, are mounted on eight-and-a-half-foot-tall metal boards arranged into a tightly spaced sequence of rows illuminated by bright white lights. Taken as a whole, the hulking structure resembles both a cathedral and an assembly line—the act of looking is both sacralized and alienated, compared to Frazier’s earlier work. The narrow confines of the viewing space and the popularity of the exhibition make one feel compelled, like the strikers in ’72, to pick up the pace to get through all twenty-one rows. But there is simply no way to do so and have a genuine experience of the piece.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Marilyn Moore, UAW Local 1112, Women’s Committee and Retiree Executive Board, (Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co., Lear Seating Corp., 32 years in at GM Lordstown Complex, Assembly Plant, Van Plant, Metal Fab, Trim Shop), with her General Motors retirement gold ring on her index finger, Youngstown, OH from The Last Cruze, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone gallery. © LaToya Ruby Frazier.

A good deal of artistic interest has been transferred from the photos to the texts, which provide little portholes into hell. When we step inside the hidden abode of production, families are torn apart, bodies rent asunder. Jason Duncan, who worked in the fabricating plant alongside his father, recalls his dad doing twelve-hour shifts, seven days a week: “we didn’t have no communications other than a phone call on his lunch break.” In a scene straight out of Weems, he’s shown seated at a kitchen table staring into the eyes of his young daughter. His wife and mother stand behind them, wearing union-branded sweatshirts. Jason’s father-in-law, Ted Carpenter, is pictured in a nearby image with a collection of T-shirts commemorating the Flint sit-down strike of ’36–’37 and Civil Rights initiatives within the union. He describes his life at the plant succinctly: “hot metal piercing my skin!”

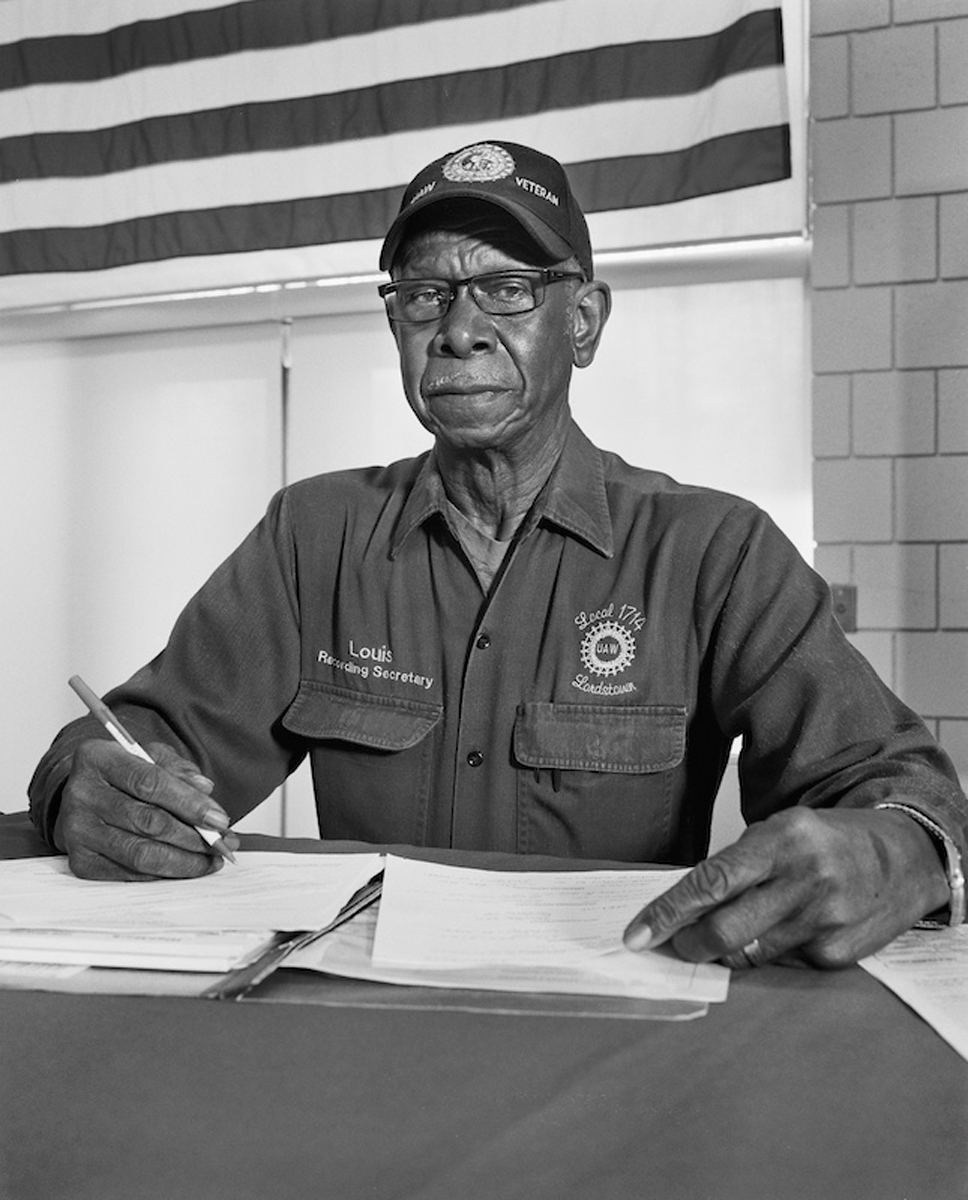

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Louis Robinson, Jr., UAW Local 1714, (34 years in at GM Lordstown Complex, die setter), Recording Secretary, at UAW Local 1112 Reuther Scandy Alli union hall, Lordstown, OH from The Last Cruze, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone gallery. © LaToya Ruby Frazier.

The maximalism of The Last Cruze performs a disciplinary function: it makes demands on our attention that the earlier works do not. Who can sustain so much looking and so much reading? Like the Fordist jobs it records, the piece raises the question of the political production of boredom—a mood that modern art has long incorporated to stave off the encroachments of the culture industry. At issue is not whether the project is interesting—it emphatically is—but whether we can resist distraction for long enough to see it all the way down the line. The Last Cruze is a systematic, rigorous exploration of the six-million-square-foot Lordstown plant, its place in the history of the American labor movement, and the lives of the fifteen-hundred workers employed there. The installation provides a formal solution to the matter of how to represent impersonal forces, to transform the mute compulsions of capital flows into objects of apperception. Difficult to process though it may be, this wealth of information, the legacy of photo-driven conceptualism of which Frazier is heir apparent, is essential to grasping the material and spiritual stakes of industrial policy at issue. The balance of forces illuminated by Frazier is constituted by social and economic relations, the “web which has been, and continues to be,” according to Marx, “woven behind the backs of the producers of commodities.”

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Monuments of Solidarity, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured, left: Dolores Huerta Standing in front of Harvey Wilson Richards’s Photograph of Grape Pickers, Farm Workers, Community Members, and Supporters on their 340-Mile Peregrinación (Pilgrimage) from Delano to the Steps of the State Capitol in Sacramento, March–April 1966, in the Exhibit Hall at the César E. Chávez National Monument (Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz), Keene, CA from A Pilgrimage to Dolores Huerta: The Forty Acres, Arvin Migratory Labor Camp, Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz, Dolores Huerta Peace and Justice Cultural Center, 2023–24.

Among the more than one dozen references to scripture in the artist’s credo opening the exhibition catalog is the word agape. For Martin Luther King, this love, which redeems the workers’ unearned suffering, would, if practiced, guarantee victory in the struggle against militarism and racial and economic injustice. Frazier works with a militant love for the proletariat; her photos extinguish the images of ignorance and bigotry associated, in the Trump-era and today, with talk of the American working class, and counterprograms her audience with pictures from a solidaristic, woman-led, and multiracial movement. When leaving the exhibition, you hear Frazier playing a glimmering rendition of “Solidarity Forever” on electric guitar, but it may just as well be “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” with which it shares a tune. The Hymn’s first words are quoted by Dr. King at the climax of his final speech, delivered in support of striking sanitation workers. His truth is marching on.

Ciarán Finlayson is Senior Editor at Triple Canopy. He is the author of Perpetual Slavery.