Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Kevin Beasley’s art-book and double-LP project explores sound and US history through a cotton-gin motor purchased off eBay.

Kevin Beasley, A View of a Landscape, 2023. Courtesy Renaissance Society.

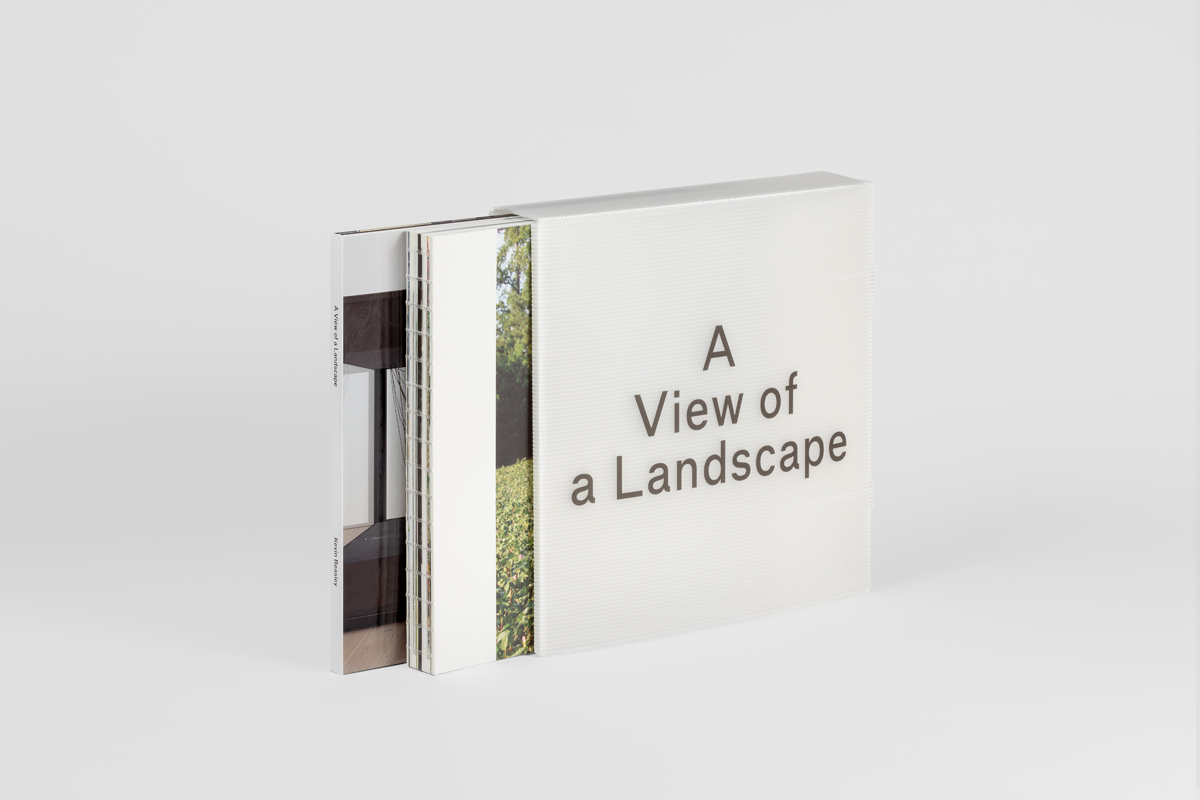

A View of a Landscape, 300-page book edited by Karsten Lund and Solveig Øvstebø and double LP featuring Kevin Beasley, Laurel Halo, Jlin, Eli Keszler, Ralph Lemon, Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, Kelsey Lu, Jason Moran, Fred Moten, Moor Mother, Okwui Okpokwasili, and SCRAAATCH, produced in partnership with Hyperdub,

Renaissance Society, $100

• • •

Art books are often the byproduct of an event, like a gallery show or a museum exhibition. Kevin Beasley’s A View of a Landscape, though, was conceived from the beginning—2016, roughly—as a large-format monograph and double-LP package that references past work but lives independently as a freestanding piece. Much of Beasley’s practice deals with a particularly American kind of weight, and this project embodies and, literally, expands on that.

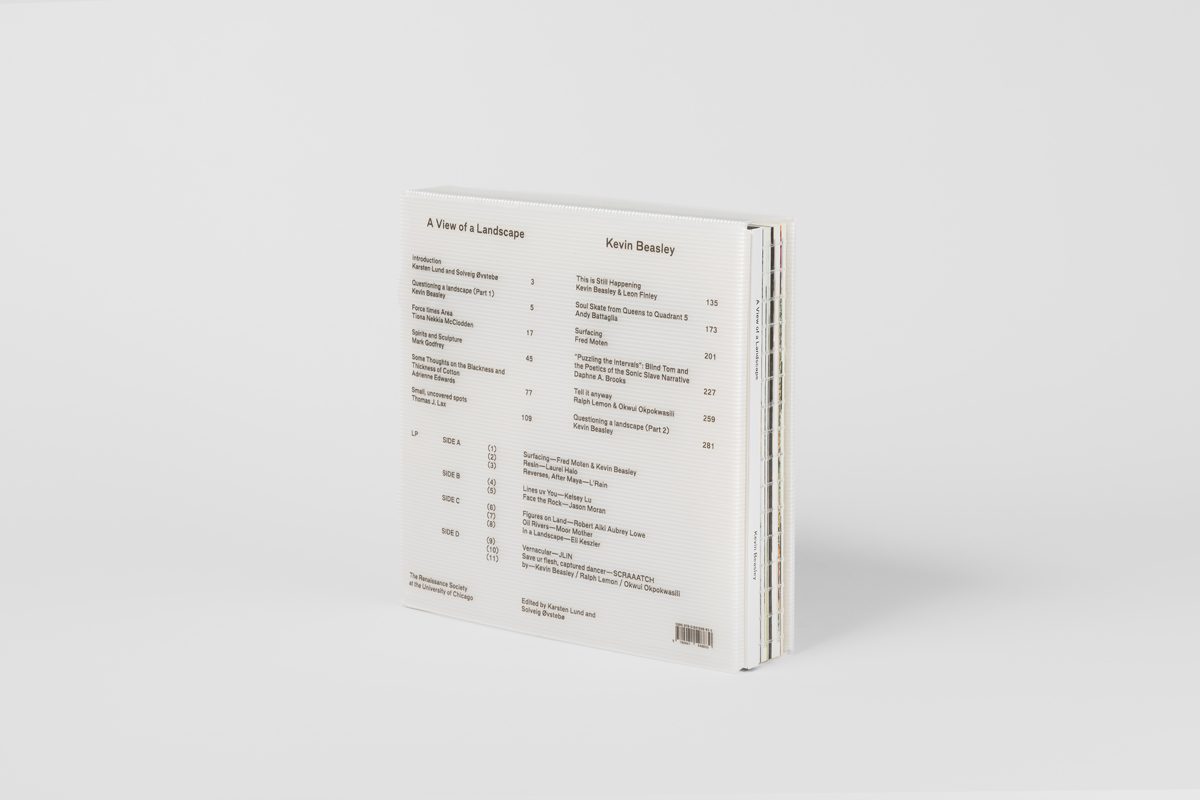

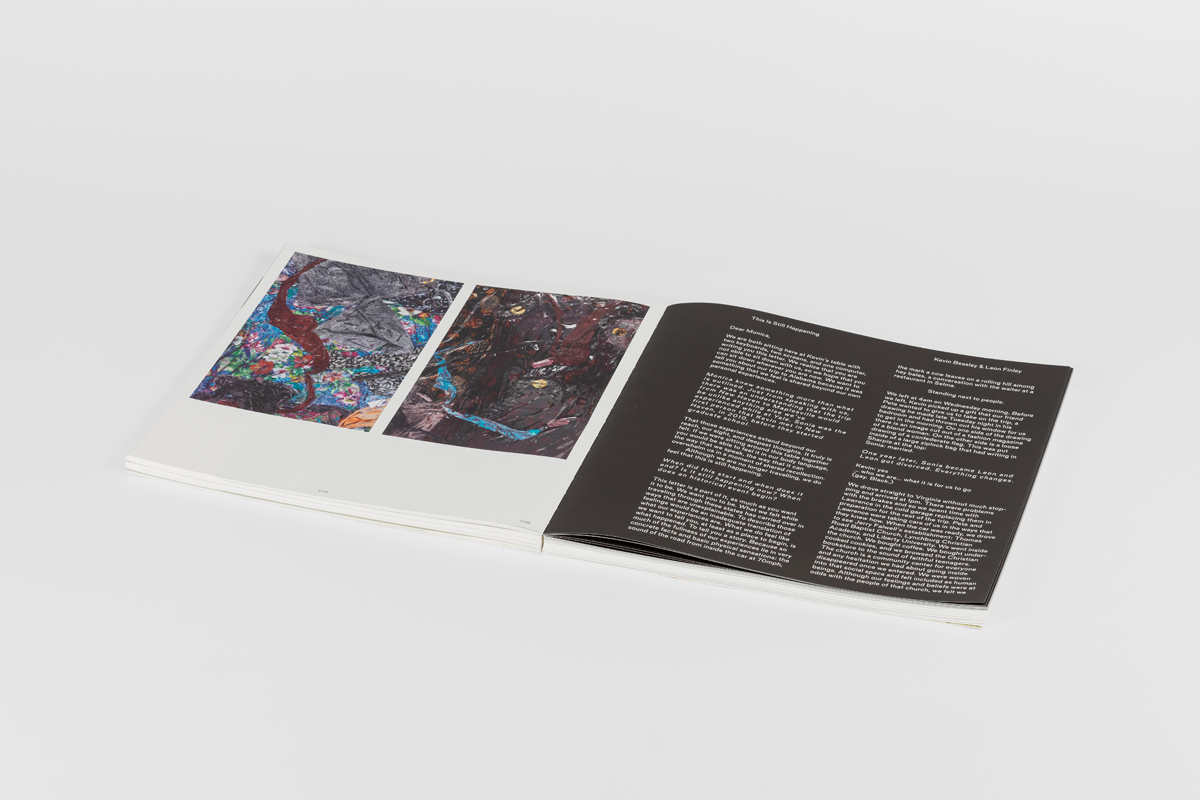

Housed in a corrugated plastic box, this 300-page book and double album unfolds twice, into four full panels. The book is open-bound with an exposed spine and lies perfectly flat when you open it. This choice alone merits a Nobel Prize, in that it prioritizes the experience of the reader (especially rare with fine-art titles). The book and album are beautifully tangled up; the texts you hear Fred Moten and Ralph Lemon and Okwui Okpokwasili recite on the album are reproduced, along with essays by Thomas J. Lax and Adrienne Edwards and other colleagues, all surrounded by photos from Beasley’s life and of his art. The type is sans serif (meh) and huge (fantastic), meaning that as you look through the images, the monograph is a bit like a mini gallery show with legible wall copy, and is easier to look at than most physical exhibits. Even with all this lavishness, it only lists for $100, though the run is capped at one thousand copies. Considering how many different ways you can go out to see art and easily blow through money in the process, this feels like a fairly democratic product.

Kevin Beasley, A View of a Landscape, 2023. Courtesy Renaissance Society.

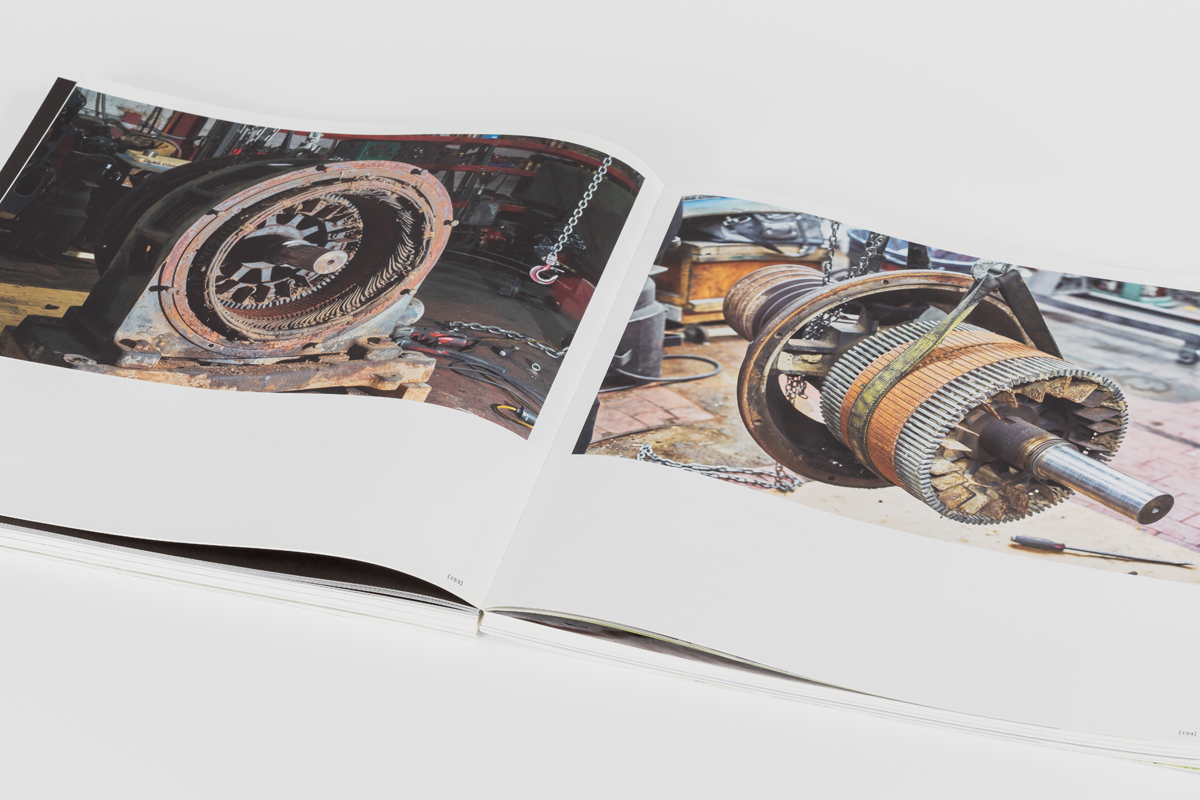

The book draws heavily on Beasley’s 2018–19 Whitney show, also called A view of a landscape, which centered on a gigantic 1915 General Electric induction motor originally used in a cotton gin, encased in soundproof glass but mic’d up and feeding signals into an adjacent gallery. (A third room contained some of Beasley’s massive resin sculptures, which capture bundles of clothing and other found materials, fixing them into rectangles that can reach up to fourteen feet high and look like load-bearing walls made of laundry.)

The inspiration for the exhibition came in 2011, when Beasley was a graduate student in sculpture at Yale. He went down to Virginia for his annual family reunion and saw that cotton was planted on the nine-acre estate owned by his relatives in the town of Valentines. His great-great-grandparents had likely been slaves, possibly on this same plot of land. “The baby hair on the back of my neck straightened and I was emotionally bent out of shape,” Beasley writes in an essay in the book. “I saw a cotton field for the first time, and it felt out-of-body. Who is picking cotton now?” The cotton growing there in 2011 was being farmed by various planters leasing the land from his family. Beasley writes that he was “ready to deal with the fact that my family is descended from slave labor in this country” and with the “scar not only on the backs of Black people but also on the human psyche.” The first step was finding a cotton-gin motor on eBay, and then driving south to collect it in Alabama.

Kevin Beasley, A View of a Landscape, 2023. Courtesy Renaissance Society.

The engine is a totemic container for the dissonant field of consciousness that contains what Beasley describes as his own “pleasurable” experience picking cotton as well as the “psychological pressure of picking as a slave under severe circumstances and consequences,” and other states of mind. The motor was originally housed thirty miles away from Selma in the early twentieth century. What was it a part of? What did it hear and see and absorb?

Kevin Beasley, A View of a Landscape, 2023. Courtesy Renaissance Society.

How Beasley made that work in the Whitney was to divorce the engine from its own sounds and lead the viewer to wonder what this visibly functioning motor was doing, and where it came from. Its hum became the raw material (the sound cotton, maybe) for the exhibit, and then for the musicians. The LP has a photo of the chambered motor across its gatefold, an image also reproduced numerous times in the book. Within its glass encasing, surrounded by microphones, the motor looks like a witness on the stand in a courtroom. Viewed in these photographs, its smooth gray surfaces are distinct from the rest of Beasley’s physical art, most often represented here by his textile and resin pieces, which he calls “slabs.”

Kevin Beasley, A View of a Landscape, 2023. Courtesy Renaissance Society.

As Adrienne Edwards puts it in one essay, “the thickness of Kevin Beasley’s objects is perhaps their most distinguishing feature.” If we extended thickness to include psychic weight, physical texture, and sonic impression, it really is the right word. The slabs look wet and just born, in that the resin soaks the fabric and darkens it. To the touch, it’s all rock-hard, even if it never appears to be. Sometimes the slabs are composed largely of cotton tufts, a material that rarely looks heavy, no matter how much of it you assemble. When I visited Beasley’s studio in March, there was an almost-full bale of cotton near the door, still mostly compressed, with one end raw and easily pulled apart. As an American who grew up with songs like “jump down, turn around, pick a bale of cotton,” I somehow didn’t know that a bale was almost five hundred pounds, and that it’s going for a little less than a dollar a pound now, and that raw cotton is even softer than you’d expect. And cotton is still, like land and motors and families in America, an inescapable and tangible social fact. You can’t put cotton’s story back in the ground.

Kevin Beasley, A View of a Landscape, 2023. Courtesy Renaissance Society.

You can play it, though, which is part of what the music here accomplishes. I have no idea if the book accompanies the record or vice versa—there is no perceptible hierarchy between them. The phrase “supply chain” has returned a sense of political economy to everyday discussion in the past few years, in the way that Beasley’s gin motor retrieves the physical history of cotton. A View of a Landscape was not immune to that chain—the music and the vinyl were completed over two years ago, long before the texts and images. The music around this project has moved in four phases: the original performances by Beasley, Jlin, Taja Cheek, and drummer Eli Keszler at the Whitney, as part of the exhibit; a stretch of shows at the Kitchen in 2019; the music in this book package; and a live improvised performance at Performance Space New York in late March of this year; all of it based on samples of the motor sounds. I began thinking the motor was going on a sort of ghost tour, playing to audiences across the world in a series of sleepwalking apology dates.

On this album, Beasley and his twelve collaborators have all created their own stories of the motor, with Jason Moran’s piano resounding like an elegy played inside the motor itself and Jlin’s rubbery panic attack, “Vernacular,” feeling like the motor powering a small remote-control alarm system. The Keszler piece mimics the 2018 performances, granular and shadowy projections, the sound of metallic squibs falling on a tin roof. Having this music pressed into one bale with the texts and photos allows them all to seep into each other and bring out the pains and pleasures of living on American land, day after day.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, will be published by Semiotext(e) in October of 2023.