Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

The inner life of signals: a new album rediscovers a key figure in the history of electronic music.

Jaap Vink, Jaap Vink, Editions MEGO/Recollection GRM

• • •

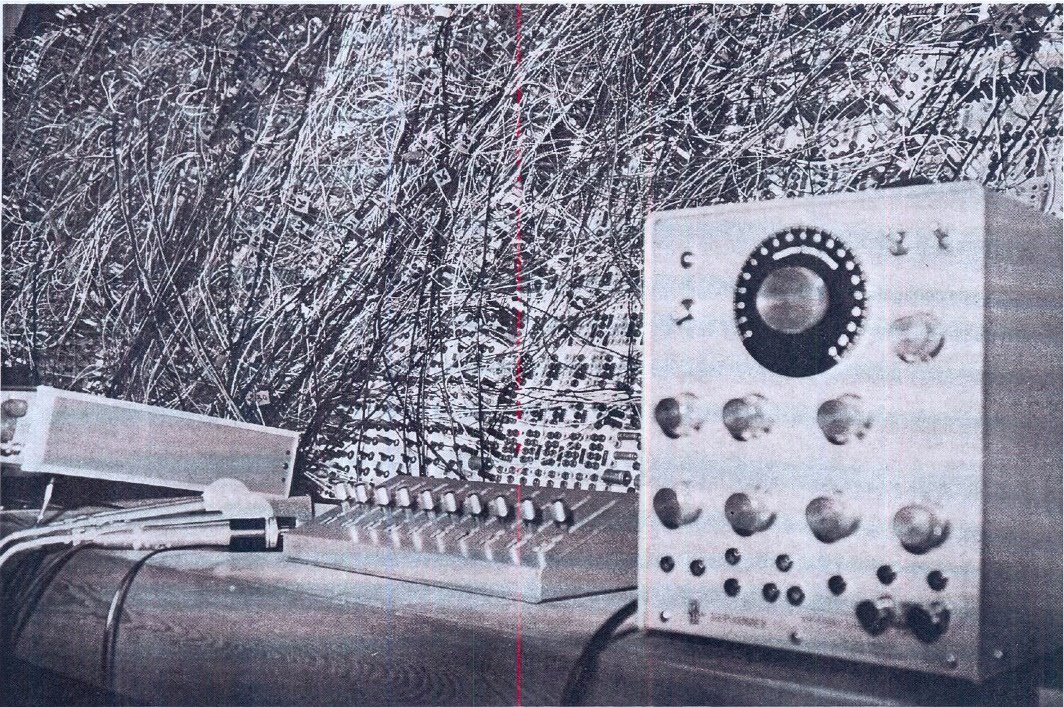

It began with a photograph. In June of 2015, François Bonnet, who performs as Kassel Jaeger and is the artistic director of GRM—the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, an organization committed to the study and development of electroacoustic music—arrived in Tokyo to play a show. He was at Jim O’Rourke’s apartment in Shinjuku. Late at night, five people sat on the floor, drinking sake and listening to records. The talk turned to an image spread across the gatefold sleeve of Roland Kayn’s 1977 album, Simultan. (Kayn was a German composer and synthesist who created sere electronic music for almost forty years before his death in 2011.) You don’t need to see the photograph—just imagine a large board with many input and output jacks. Hundreds of patch cables, maybe thousands, connect these points. A tiny mixing board sits in the foreground, along with a tone generator and a microphone. As Bonnet wrote to me, “This synth looks like no other. It’s massive, with so many connections. We were wondering what this synth was. Where was it? Did it still exist?”

After Tokyo, Bonnet visited the Institute of Sonology in The Hague. He asked two of the faculty members, Paul Berg and Kees Tazelaar, if the photo had been taken at the original location of the Institute, in Utrecht.

It had not. It was taken where the Kayn piece was originally recorded—in the Brussels studio of Léo Kupper, Belgian composer and electronic music pioneer. The synth in the photo was invented by Kupper and known as GAME (générateur automatique de musique électronique). It does still exist.

Tazelaar suggested that the person of interest was not in the picture. Jaap Vink, a technician at the Institute of Sonology, was the person who helped Kayn create that forest of patches and “semi-autonomous systems” of musical generation.

After receiving Vink’s blessing, Tazelaar sent Bonnet the tapes of almost everything Vink had recorded. (Now in his eighties, Vink lives in the northern Netherlands and doesn’t travel.) Bonnet then sent the recordings to O’Rourke, whose enthusiasm for the material inspired him to figure out a way to release it all. Though Vink was never associated with GRM, Bonnet thought his work important enough to release through Recollection GRM, a historical arm of the GRM label operated in collaboration with Editions Mego.

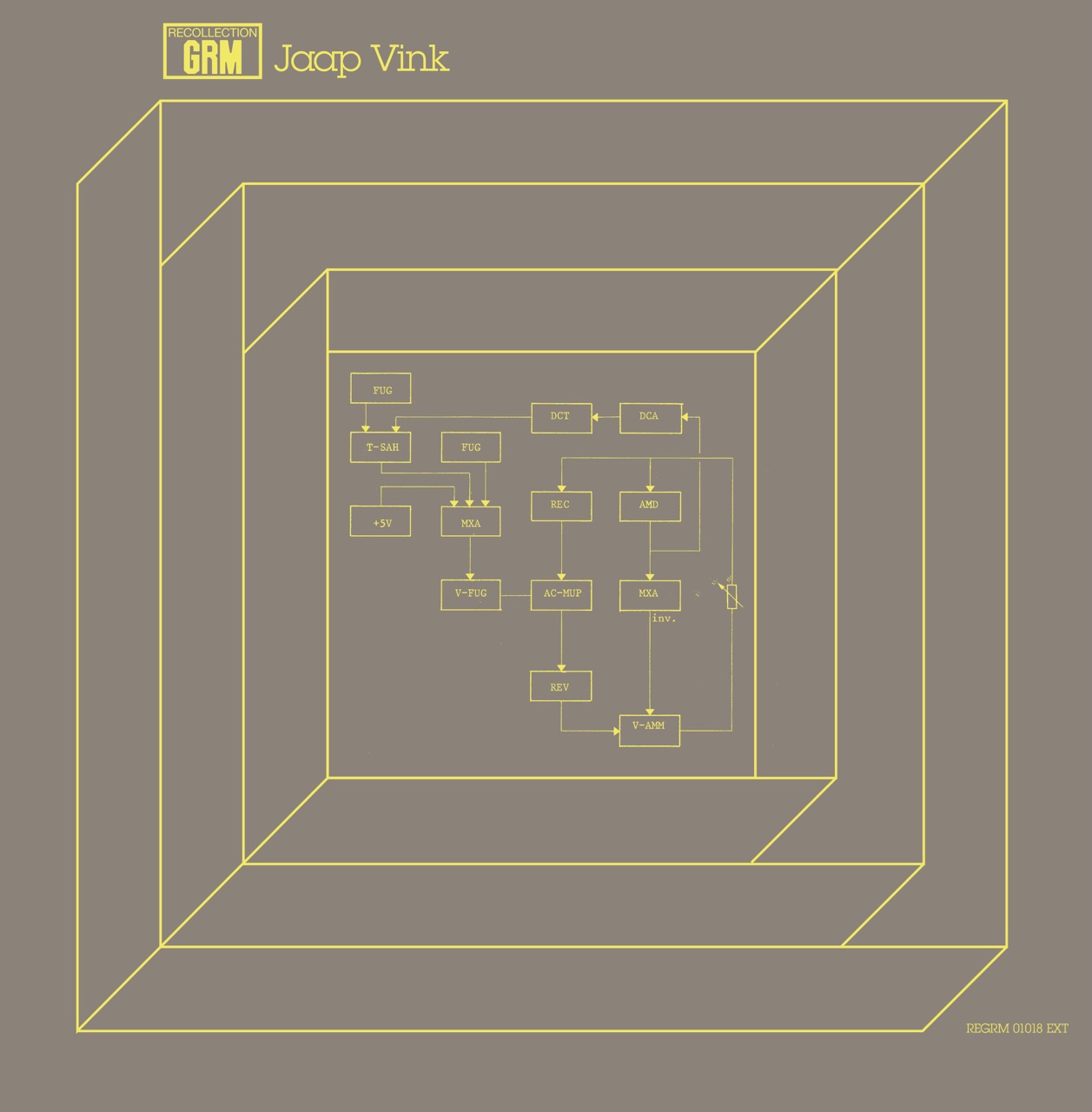

The Vink release recovers a key part of the history of electronic music. Vink considered himself a technician—he said he was “too lazy to compose.” But the Institute of Sonology put on a fair number of concerts, and occasionally one of the staff would ask Vink to contribute something to a live performance. Vink then taped the output of whatever array of synthesizers and tape recorders he was working on and gave that recording to the concert organizers. Bespoke and passive, this approach yielded seven pieces over roughly twenty years. (The most recent material in the collection dates from 1985.)

The only piece to reach the public around the time of its creation is a track called “Screen,” recorded in 1968 and issued in 1970 by Philips on a four-LP set that has become increasingly important over time: Electronic Panorama: Paris, Tokyo, Utrecht, Warszawa. “Screen” builds slowly, a combination of noises pink and white plus tones that have character but no identifiable pitch. It sounds more or less like a jet taking off and landing over seven and a half minutes, though all the unrelated detail suggests you are not hearing any kind of airplane. There is nothing melodic about the piece and few people who aren’t familiar with modular synthesis and tape feedback could tell you immediately how it was made.

Another reason the Vink release is more than a footnote in the development of electroacoustic music is that electronic music is now enormous and hard to define in both function and character. In the 1970s, musique concrète and electroacoustic music were not brought up in the context of more popular electronic musicians, like Kraftwerk. Now, these streams have all converged and younger electronic musicians working with both software and hardware are aware of people like Pierre Schaeffer, founder of GRM and father of musique concrète. Having access to the work of someone like Vink, who was exploring the possibilities of sound with the best analogue equipment available, while free of any commercial restraints, is not a minor development.

Vink’s interest was to escape the periodic waveform, which means that he did not want his electronic tools to make sounds that were recognizable as electronic. Vink’s mission was a fairly clear dialectic: an almost hermetic electronic system was being engineered to create sounds that resembled natural phenomena, signals that had “an inner life,” as Tazelaar put it. Vink introduced input from one source or another, but much of the sound was coming from the feedback generated within a system of tape machines and synthesizer modules chained together. If we think of voltage as a natural occurrence, then this is a natural process: signals varying as they meet and combine, with only intermittent human intervention.

The pieces on the new Recollections GRM album that were recorded around the time of “Screen” develop a similar template of sustained tones that grow and change in color. “Objets Distants” (1970), “Granule” (1970), and “Residuals” (1971) all manipulate a blend of windy, thick noise and higher, semi-tonal elements. The rate of change is relatively slow, and the focus seems to be almost chromatic: how many iterations can one idea yield without radical, obvious shifts? You will not hear any traditionally musical framework, like motif or rhythm. Especially when tones overlap and rattle, Vink’s work posits a physical place, like the one suggested by the low roars and shredded beeps in the sound design of Alien. Vink’s material moves, if slowly. One of the best moments on the new album is the end of “Residuals,” when the signals drop into static and the track sounds like a hose flapping around the corner of a building, active but more randomized than what Vink usually opts for.

In the 1980s, Vink adds the component of tuning, or at least notes that are harmonically aligned and perceptible. “En dehors” (1980–85), “Stroma” (1982), and “Tide 85” (1985) are kin to the earlier works, in terms of the pacing, but the addition of definite pitches and elements that mimic horns (they’re not horns, though) brings Vink even closer to soundtrack territory. Which doesn’t make his research any more or less useful. A central object of study with groups like GRM is the nature of sound: what is being referred to, and what is being suggested? Sit through the ninety minutes of this album and you hear the output of a self-contained world that doesn’t need the pre-existing world of music. It is a related planet, one that aligns with ours while having its own qualities, its own tendencies. Vink and his colleagues were listening unusually closely to electroacoustic processes that were going to become embedded in our lives. Their past is our present.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician from Brooklyn.