Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

The Case of the Missing Sex Diary: Paul La Farge’s new novel imagines the romantic life of H.P. Lovecraft.

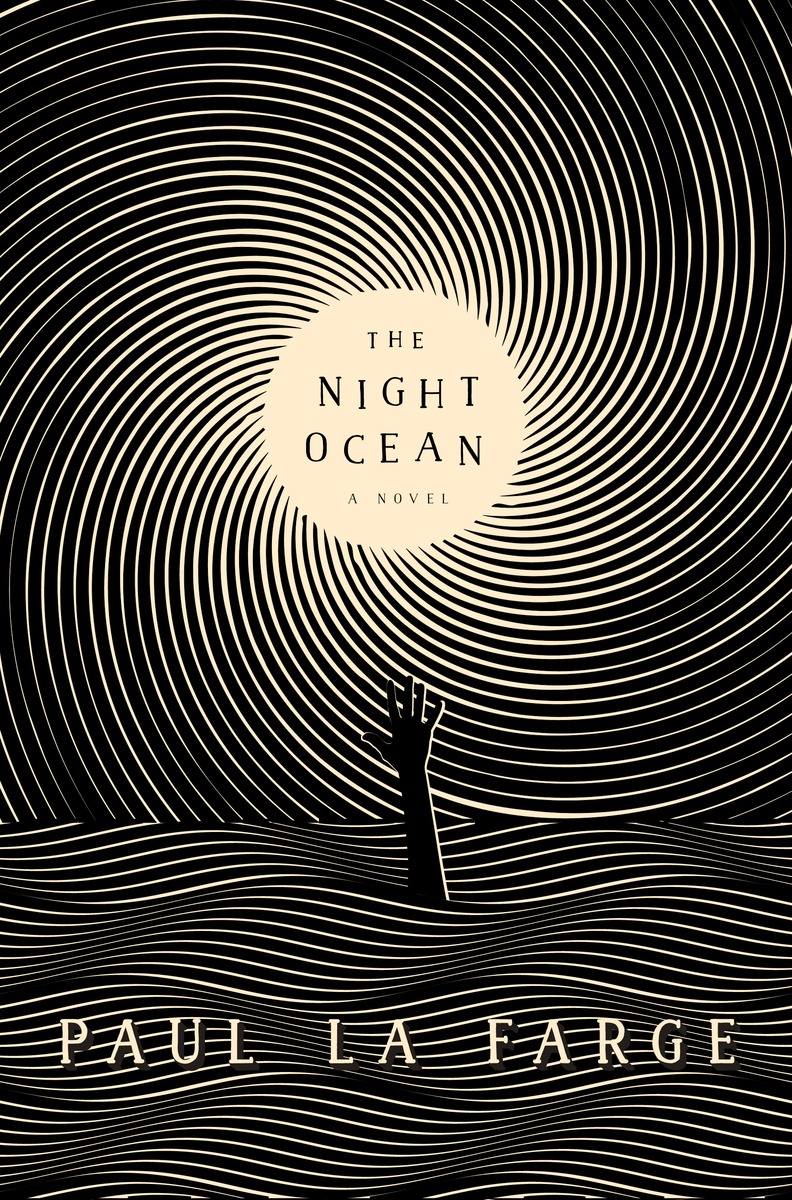

The Night Ocean, by Paul La Farge, Penguin Press, 389 pages, $27

• • •

Twenty years ago, my friend Nikola received a promo copy of Elliott Smith’s Either/Or. It arrived in a clear plastic baggie, with nothing but the artist’s name, the album title, and the song names. He fell in love with the album knowing nothing of Smith’s addiction, his growing cult, Los Angeles, or anything external to the music. It’s a good protocol, the baggie test. How do you respond to work without any context, aside from the one you create?

I can’t recall a book that failed the baggie test for me as fully as The Night Ocean did. I had read neither Lovecraft nor La Farge before this novel, and felt badly about the lack. I feel fine about it now. After finishing The Night Ocean, I confirmed that it is based on an actual meeting in 1934 between H.P. Lovecraft and a fan named Robert Barlow, his junior by twenty-seven years. It’s a historical fact that Lovecraft’s visit with Barlow in Florida lasted two months, but whether or not they had any sexual contact is unclear. Much of The Night Ocean is extrapolation, a fantasy about what might have happened between Barlow and Lovecraft, as interpreted by a series of characters grappling with the ghosts of both.

If you are not already immersed in Lovecraft’s work, weighting the events—both real and imagined—is a problem. The interaction between known knowns—the structure of La Farge’s book is apparently modeled on that of Lovecraft’s very real The Case of Charles Dexter Ward—and the known unknowns (Lovecraft’s sexuality) will be active chemistry for those who are versed in Lovecraft. For this uninitiated reader, The Night Ocean was a very long list of names and characters that tumbled out, one after the other, without sticking.

La Farge buries secrets inside of secrets by wrapping the story of Lovecraft and Barlow in the narratives of fictional characters (apparently mirroring the structure of the Charles Dexter Ward book). First, we are introduced to Charlie Willett, a journalist, whose story is narrated by his wife, a doctor named Marina Willett. Eventually we meet L.C. Spinks, an editor who might have collaborated with Lovecraft. Much of The Night Ocean hinges on the Erotonomicon, a book that appears to be a catalogue of Lovecraft’s sexual exploits, and which Spinks annotated. The Lovecraft adept will understand immediately that the Necronomicon, a book of spells that Lovecraft imagined (but did not ever write) and then mentioned in several of his books, is the original signal, and the Erotonomicon, conjured by La Farge, is its echo. Charlie Willett discusses the mystery around both books; for the Lovecraft fan, this subtly introduces the idea of the literary Sasquatch. For a beginner, all of the puzzles feel equivalent, stacking up in a way that prevents entry into La Farge’s spiral. If you aren’t invested in the original texts of both Lovecraft’s work and his life, a meta-text like The Night Ocean functions like the tunic of an onion without the flesh: lots of husk, no meat.

Once we meet Lovecraft, the novel stops spinning and digs into the Erotonomicon, which is quoted repeatedly. For anyone hoping to understand Lovecraft’s value as a stylist and position in the horror genre, the excerpts that La Farge creates are confusing, at best. The Erotonomicon is a spank-bank journal written in made-up slang with hints of old English. Lovecraft—or the person pretending to be Lovecraft—uses the Erotonomicon to record sex acts almost exclusively.

[Barlow] proposed we try a joint Yogge-Sothothe—in a glass-bottomed boat! We were on the far side of a green-tufted island, out of sight of our fellow pleasure-seekers, but, “Ye Gods,” I exclaim’d, “what if we are observ’d from Below? “‘From Below’ would make a good title for a story,” quipped Bobby. I told him not to be foolish.

The quips of this Lovecraft’s world feel like dad jokes, here and elsewhere in the novel. (“Yogge-Sothothe” is masturbation, which may be a kind of deeper code for Lovecraft experts.) Lovecraft and Barlow do ablo and aklo and yogge-sothothe in Florida, and then Lovecraft ups and dies. The Erotonomicon turns out to be a source of shame that ruins Lovecraft’s reputation; Barlow flees to Mexico City. Charlie Willett heads out to discover what happened to everyone in this matrix, and layers of hoax are revealed.

Especially in the early sections of the book, where Lovecraft’s sexuality is the main topic, La Farge’s tone duplicates the prurience of a teenage boy flipping through forbidden magazines and pretending he’s in the Scooby Doo gang. La Farge’s intention may be, precisely, to replicate the state of mind of a teenage pulp-magazine reader like Barlow encountering Lovecraft in the only places he published before his death. As a result, The Night Ocean rarely feels like it was written by, or for, an adult.

It also rarely feels like a book about someone whose writing for cheap horror magazines was powerful and strange enough to grow into a force of its own after the author’s death. We are never shown what made Lovecraft great, despite his many flaws. His sexuality was not one of these flaws, despite the tone of The Night Ocean’s first hundred pages. His very real anti-Semitism and racism were, though these come up later in the book—way too late.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician from Brooklyn.