Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Language rushes to keep up with the chaos of science in Benjamín Labatut’s new hybrid novel.

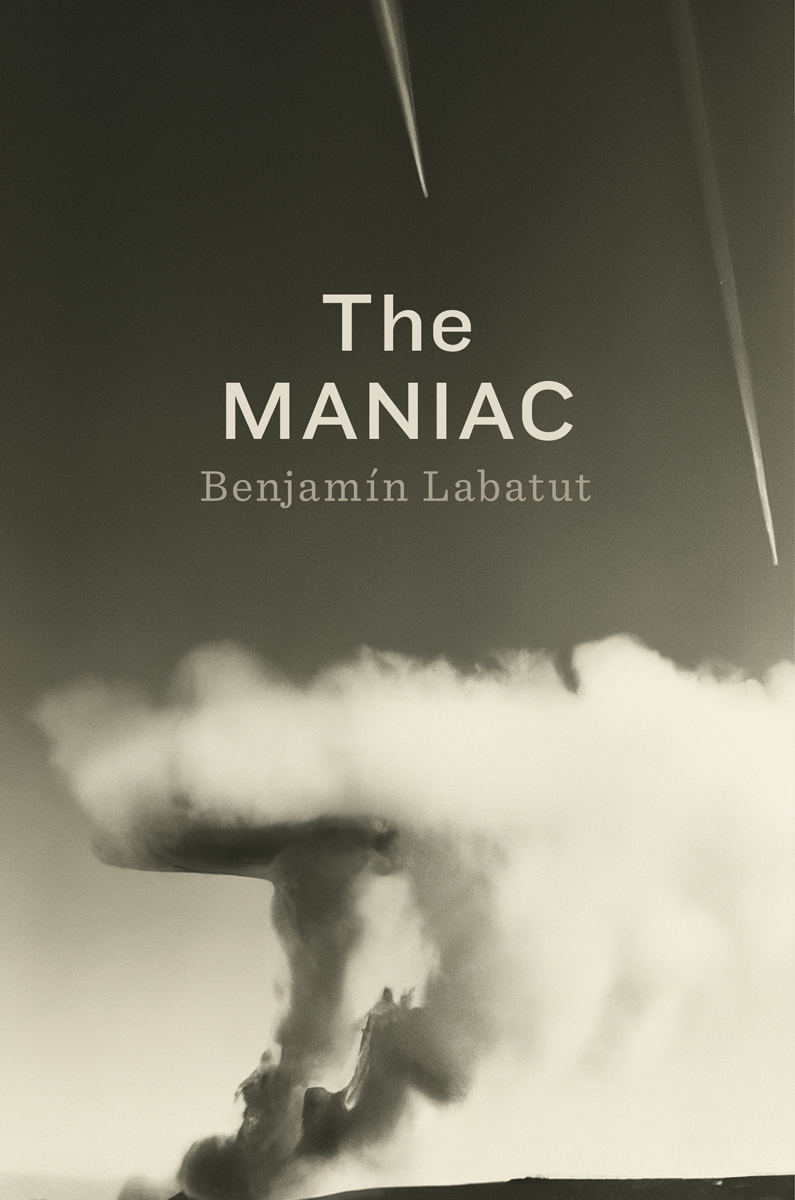

The MANIAC, by Benjamín Labatut, Penguin Press, 354 pages, $28

• • •

It is worth asking why Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand The World was nominated for the International Booker in 2021 and a terminally online person making Barbie and Oppenheimer fuck behind the Bitcoin ATM will not make this year’s cut, though Labatut’s new novel, The MANIAC, might. To this reader, it’s all fanfic, which is no insult. The famous are always found in Labatut’s pouch of beloved scientists. In When We Cease, it was a small gang including Fritz Haber and Heisenberg, while in The MANIAC, Labatut fans out over John von Neumann, a Hungarian responsible for, among other things, an early computer known by the acronym MANIAC: Mathematical Analyzer, Numerical Integrator and Computer.

I don’t think Labatut would mind if his books were perceived as a part of the chaotic demotic: loving, unruly, and speculative. In one interview, he objected to the descriptor “novel,” saying he doesn’t like writing or reading them. He went on to say that When We Cease begins with a “not chemically pure essay” (a hallucinatory triumph called “Prussian Blue”), which is followed by short stories and an autobiographical sketch about dogs being poisoned near his home in the Chilean mountains. What The MANIAC is missing is something as vivid and sleek as “Prussian Blue,” a necklace of facts that disorient and disgust as they fall through your hands. For The MANIAC to work, we would need something as aesthetically pleasing as that essay, or a point that goes beyond “Don’t trust scientists to be moral.”

Neumann is introduced (after a grim opening section about a scientist named Paul Ehrenfest, who shoots his own child and then disappears from the book) with this sentence, isolated on its own page: “He was the smartest human being of the 20th century.” Fellas—we got him: the main guy. Gather round. Labatut then follows with a list of what von Neumman is responsible for, thanks to a mind that has “birthed the modern computer, laid down the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, written the equations for the implosion of the atomic bomb, fathered the Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, heralded the arrival of digital life, self-reproducing machines, artificial intelligence, and the technological singularity, and promised them godlike control over the Earth’s climate.”

When the mood is not tumescent, we seem to be in a ’50s sci-flick where someone is constantly running into a room to re-table the stakes of science itself. The following bit is from the Paul Ehrenfest section but appears in different guises throughout The MANIAC and the later sections of When We Cease: “To acknowledge even the possibility of the irrational, to recognize disharmony, would place the fabric of existence at risk, since not just our reality, but every single aspect of the universe—whether physical, mental, or ethereal—depended on the unseen threads that bind all things together.” The apocalyptic tenor has a short shelf life, and since we know that, you know, the atomic bomb was bad, the telos of Labatut’s game here is more than a little odd. Little of the science undergirding The MANIAC is explained—so, tough luck, nerds.

What would relieve all this are those old fiction standbys present in most fanfic: scenes and dialogue. Not for Labatut, these cheap kicks of narrative. The MANIAC is almost all tell without show. The various von Neumann sections are attributed to characters, as if told in their voices, but other than Richard Feynman, who does get his own clipped cadence, everyone speaks in the run-ons that serve as Labatut’s default. If any of this happened in scenes or with a real-time sense where things elapse, it might stick. Labatut rarely hits a fresh page without a run-on sentence in hand, and if he sees one adjective or adverb, by golly, a companion is tacked on. “Brilliant” and “genius” are used many, many times, less as judgements and more like soldiers in a generally aphrodisiacal campaign of language. The line here tends to the erotic, bending to a hint of military pressure. What we are left with is hundreds of pages of description, floating a few inches beyond the reader’s emotional grasp.

Sometimes, Labatut gets close to a thread that might land his balloon. One of von Neumann’s friends, Oskar Morgenstern, delivers a lovely distillation of the truth that all of Labatut’s scientists can’t seem to absorb. Humans are not, in fact, the “perfect poker players” of life itself. They are “driven and swayed by their emotions, subject to all kinds of contradictions,” a classification that suits the scientists who see themselves as above all that. “And while this sparks off the ungovernable chaos that we see all around us,” Morgenstern says, “it is also a mercy, a strange angel that protects us from the mad dreams of reason.”

Labatut’s stories ignore those strange angels, though, and hammer away at the mad dreams of reason, this fanfic boy’s particular kink. The problem with fanfic is that it bends not to the arc of history or the demands of character but to the climactic release that the author needs to experience, over and over. The scene settings are so similar—in both of Labatut’s books—that everybody seems to be involved with quantum mechanics or the invention of a poison gas, or to be a victim of same. Extra points if you stay up for three days not eating, are sweaty, and have an unusually small (or large) head.

I do get swept away sometimes. I am happy that Labatut has no chill about the end of the world and sees the self-mutilating onanism of science as a vivid, pulpy soap opera where fear and fascination are terrifying and voluptuous, where Einstein and Heisenberg and von Neumann and Turing are pressed together like worms and travel up through the earth to bust out like Kool-Aid, working to make things easier or faster for the common man but usually just irradiating the world with a flash of fatal arrogance.

The MANIAC reverses the flow of When We Cease and puts its most efficient story last, a carefully paced scene of Go master Lee Sedol playing a computer. Much of what concerns Labatut is here—what makes us human, what is it that AI can’t copy, what is it that math cannot capture. Even though Sedol’s story is easily found online, I don’t want to ruin the beautiful rhythm Labatut establishes for his Go battle with DeepMind’s AI player. The truly juicy paradox that animates the more piercing parts of both Labatut books is that humans are weaker than machines but humble enough to be open to the chaos of God, at their best. We hope, finally, that AI will not be able to find this strength through vulnerability, but then a new machine is created, named AlphaZero. This computer plays only itself and becomes so strong it can be as chaotic and inexplicable as any human. Some bits of Labatut’s hybrid books are confabulations, though most are based on research and reporting. AlphaZero, sadly, is real and just as powerful as Labatut suggests. The MANIAC ends up delivering the most Labatut feeling of all: complete defeat with a hint of almonds.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York. His memoir, Earlier, will be published by Semiotext(e) in October of 2023.