FT

FT

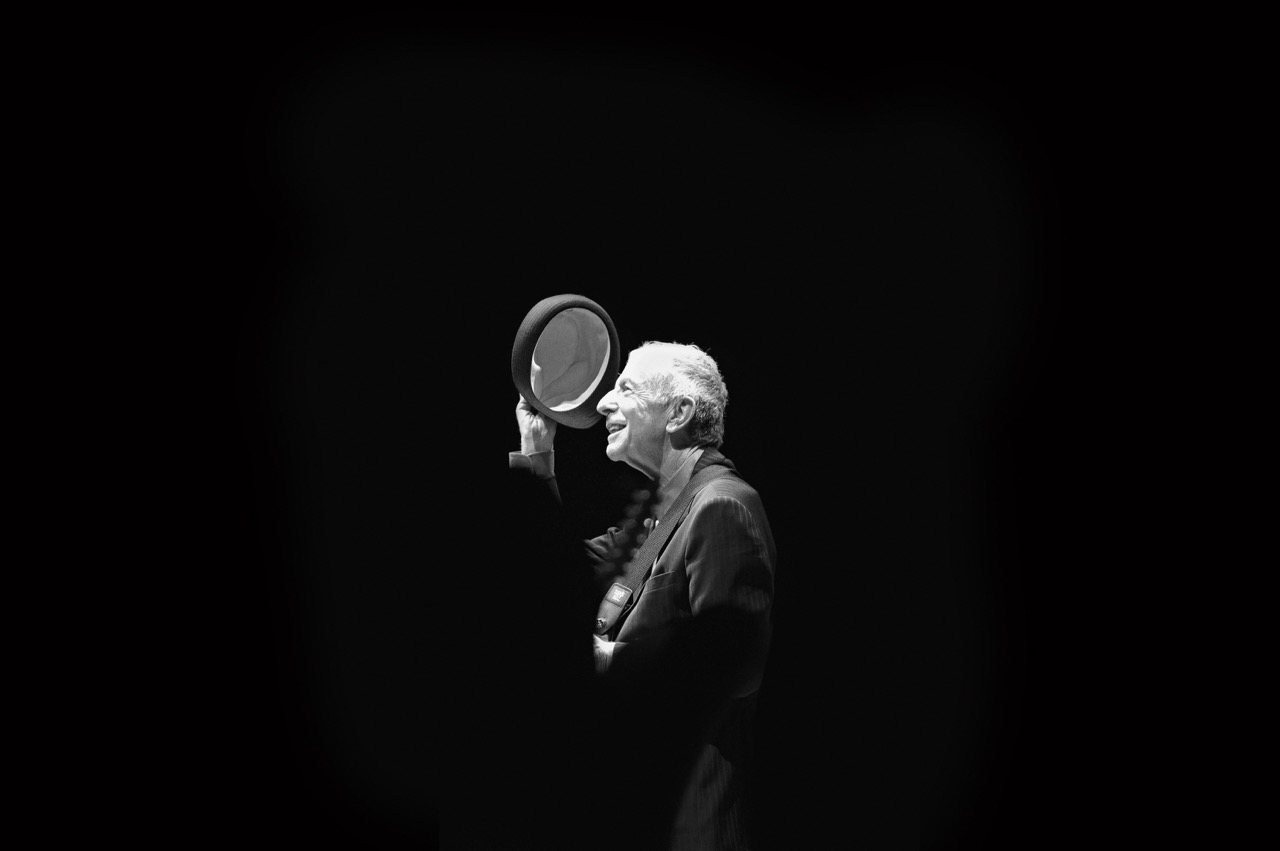

Leonard Cohen. Image courtesy Old Ideas, LLC.

Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything, the Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through September 8, 2019

• • •

Billed as “a contemporary art exhibition devoted to the imagination and legacy of the influential singer/songwriter,” Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything doesn’t quite mirror the wounded, yearning world of Cohen’s songs and poems, nor does it really explore the vast range of his cultural influence. Instead, it’s devoted to the imagination of ten artists and two collectives, each responding to Cohen’s large and complex body of work. The result is surprising and surprisingly coherent, less comprehensive but also less moribund than a straight retrospective. None of Cohen’s notebooks are here, nor his famous hats or his high school photos. Cohen didn’t commission dramatic album art or elaborate photo shoots; he didn’t wear spectacular outfits, barely deviating from dark-colored suits; he didn’t leave behind rhinestone-crusted residues of celebrity indulgence (not for lack of indulgence, but because of his general circumspection). Biography is limited to a short series of wall texts on the ground floor: the rest is sound and vision.

If the show lacks a funerary air, it might be because the pieces were commissioned not in memoriam but in celebration, for the city of Montreal’s 375th birthday. Cohen, born in the city’s Anglophone Westmount neighborhood in 1934, died at eighty-two in 2016, after the show had been planned but before the opening. About half the art in the original show, curated by John Zeppetelli with Victor Shiffman at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, is on view in the Jewish Museum’s more limited spaces—an effective selection Tetrised into three floors of the building’s narrow frame while leaving each piece plenty of room. Few of them explicitly reference his passing, but all do an effective job of eulogizing Cohen in their celebration of his life. A devotee can do the work of mourning well in these rooms, without pomp or hyperbole and without the explicit expectation of grief.

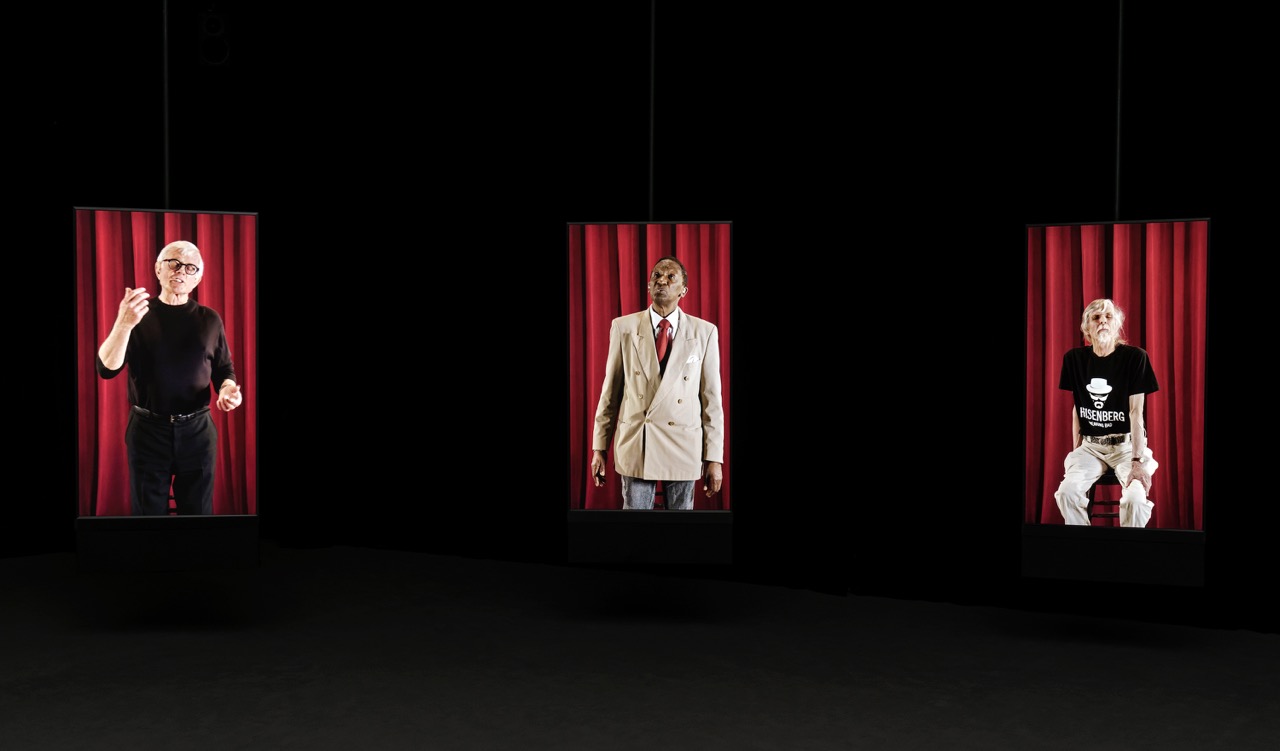

Candice Breitz, I’m Your Man (A Portrait of Leonard Cohen), 2017 (installation view, detail). 19-channel video installation, color with sound, 40 minutes, 43 seconds, featured on 18 suspended monitors and 1 single-screen projection. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Most of the pieces have a video component, and many require a good amount of time to appreciate and digest. My favorite, forty minutes long and worth every second, is Candice Breitz’s I’m Your Man (A Portrait of Leonard Cohen). Breitz invited eighteen dedicated fans, all older Canadian men, to recreate in a recording studio the full vocals to Cohen’s 1988 album I’m Your Man. On eighteen simultaneous life-size screens, the men are shown recording their vocals, track by track. Each fan sings alone to music only he can hear; we hear them singing together, the album’s thick bass and washes of synth replaced by an a cappella chorus of lyrics. In a neighboring room, an additional screen shows the men’s choir from Cohen’s synagogue in Montreal recording falsetto backing vocals; these are piped into the larger room to accompany the video chorus. The result is a hilarious, touching substitute for a Missa Solemnis. Sound, this time spoken rather than sung, is also central to Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s The Poetry Machine, a Wurlitzer organ hooked up to snippets of Cohen reading his own work. It’s hard to describe but phenomenal, suturing Cohen’s twin loves of poetry and music.

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Poetry Machine, 2017 (installation view). Interactive audio / mixed-media installation including organ, speakers, carpet, computer, and electronics. Image courtesy the artists, Luhring Augustine, Fraenkel Gallery, and Gallery Koyanagi. Photo: © Frederick Charles.

The show also recognizes the younger Cohen’s trials and passions. Ari Folman’s Depression Chamber invites the viewer to lie in the dark on a therapist’s couch while animations play. Two fascinating videos draw on the same film material, early black-and-white footage of a young Cohen standing in front of an audience in Montreal and reading a poem called “The Only Tourist in Havana Turns His Thoughts Homeward.” The poem is based on an actual trip to Cuba at a particularly inauspicious moment in 1961. The first video, Kota Ezawa’s Cohen 21, recreates two and a half minutes of the film in animation, on which geometric shapes are superimposed. Christophe Chassol’s Cuba in Cohen goes further, cutting up the film and auto-tuning the words. The resulting long-form music video emphasizes the brash disdain of the poet’s delivery and the poem’s frat boy–on-Birthright machismo; the same machismo that led Cohen to find himself in Havana during the Bay of Pigs invasion “fighting for both sides,” as he mockingly announces, the kind of machismo that can only be mustered by a young man from a well-to-do family who has never really been in a fight, much less fought in a war.

Christophe Chassol, Cuba in Cohen, 2017 (installation view). Single-screen video installation, black-and-white with sound, 15 minutes, 19 seconds, including annotated musical scores in a display cabinet. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

This pseudo-militant dick waving was a recurring aspect of Cohen’s self-fashioning: twelve years after his trip to Cuba, the amphetamine- and depression-fueled artist would find himself in Israel during the Yom Kippur War, entertaining troops on the front lines. A 1974 song is called “Field Commander Cohen.” Outside of Chassol’s video, this current is absent from the show, as is any mention of the controversy surrounding Cohen’s decision to play a concert in Tel Aviv on his 2009 comeback tour, despite his awareness of the growing Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

Daily tous les jours, I Heard There Was a Secret Chord, 2018 (installation view). Participatory audio installation, including an octagonal wooden structure, microphones, speakers, transducers, and digital display. Image courtesy Daily tous les jours. Photo: Frederick Charles.

In later years, Cohen became known for psalm-like songs of hope held together with tape and tentative optimism born of penitent desolation: when he died, the New York Times headline (front page, below the fold) was “Leonard Cohen, 1934–2016: Writer of ‘Hallelujah’ Whose Lyrics Captivated Generations.” I was wondering how long I would go before encountering that song: part of me hoped all the artists would ignore it, another part hoped the listening room upstairs would just be all three hundred or so cover versions on a loop (instead it was a soothing pastel lounge with specially commissioned Cohen covers by a range of artists). I didn’t think a fresh take on “Hallelujah” was possible, but implausibly one is offered by I Heard There Was a Secret Chord from the Montreal collective Daily tous les jours: the song is reduced to a choral buzz, prerecorded voices humming its melody. The visitor is invited to sit down and hum along into one of the hanging microphones, “closing the circuit of collective resonance with their bodies.” Cohen’s melodies—unadorned, tonally simple, written for a limited vocal range—are crucial to the effect of his songs; melody is the clearest divide between his poems and his lyrics.

Taryn Simon, The New York Times, Friday, November 11, 2016 (front and back view). New York Times newspaper in glass display cabinet, 22 × 12 ¼ × ⅜ inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Leonard Cohen died in the night of November 7, 2016, just before polls opened in the American presidential election. Taryn Simon’s contribution to the show brings the coincidence into stark relief: the piece is a simple plexiglass cube with a copy of the New York Times from November 11, the day after Cohen’s death was officially announced: above the fold is a picture of Barack Obama meeting the incoming president. A Crack in Everything takes its name from “Anthem,” a moment of redemptive clarity on a frequently grim album called The Future (1992). There’s a cover of “Anthem” in the listening room upstairs, as well as two different versions of “Suzanne.” But there’s no cover of The Future’s title track, whose lyrics read like a wry, bleak prophecy:

There’ll be the breaking of the ancient Western code

Your private life will suddenly explode

There’ll be phantoms

There’ll be fires on the road

And the white man dancing

We have the redemption, we have the celebration, and we even have the solipsistic darkness of the young poet. What I missed most in the Jewish Museum’s tribute to Cohen’s life and work was a reflection of his cynical vision of society at large, of his deep distrust of authoritarianism, and of his dystopian predictions. “Get ready for the future,” he crowed in 1992, “it is murder.” As that future hurtles toward us, I can’t imagine that Cohen would have faced it with nothing on his lips but “Hallelujah.”

FT isn’t a real person, but that doesn’t seem to stop them from having a lot of opinions. You can find their work online.