Orit Gat

Orit Gat

Death rides shotgun, literally, in Lorrie Moore’s novel about a middle-aged teacher who hits the road with his deceased ex-girlfriend in tow.

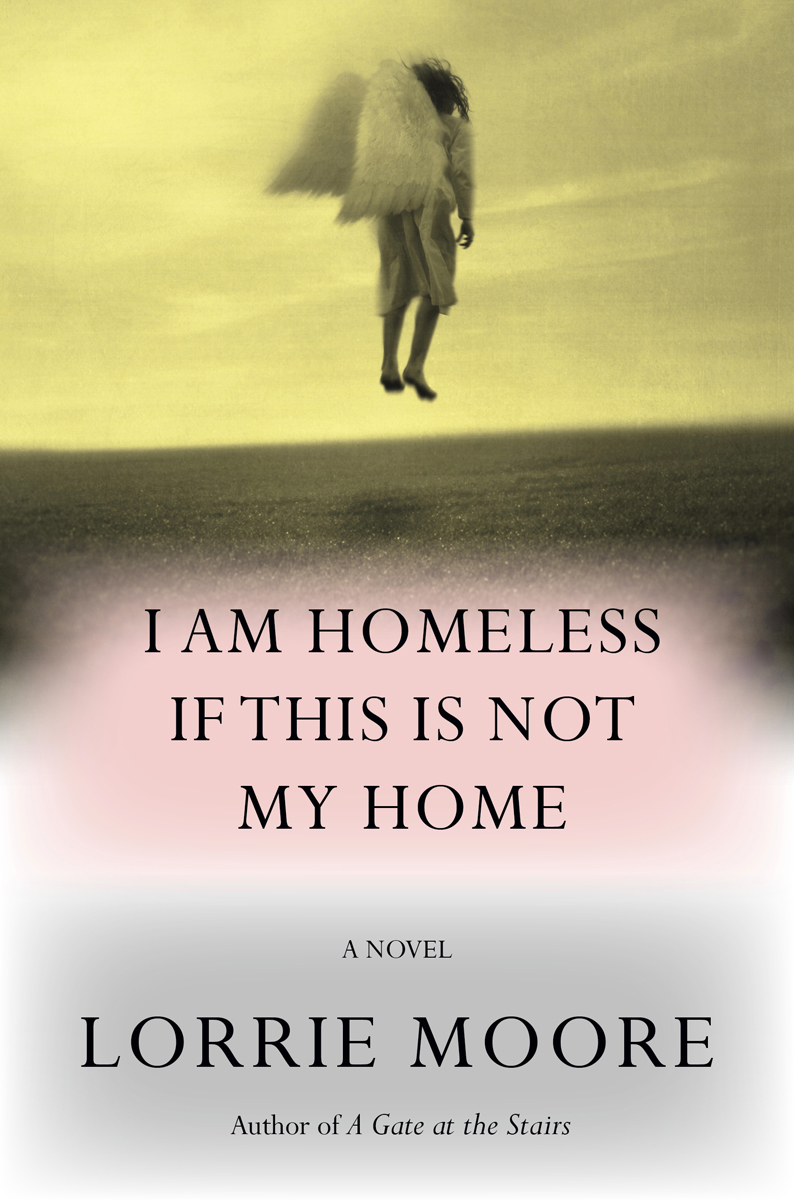

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, by Lorrie Moore,

Knopf, 193 pages, $27

• • •

Here is how some people have described their grief to me lately: like the moon (always there, even during the day when it’s impossible to see); like a damaged record (when the needle reaches the scratch it jumps and stops, but over time it may just skip a little, keep playing); like a CD whose information is jumbled, metallic, lost. People around me said it was weird—the missing, the never coming back. They said, unexpected. The experience of loss is so changeable, when death itself is evidently finite, immutable.

In I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie Moore’s first novel in fourteen years, Finn’s brother Max is dying of cancer, and Finn should really be there with him. He should also probably dump his landlady’s cat litter box, which she had asked him to get rid of for her and is now shifting around in the backseat of his car. (Readers are not told whether the cat died.) He definitely shouldn’t snatch the body of Lily, his late ex-girlfriend; and maybe he doesn’t, it’s not exactly clear. What is clear is Lily had died by suicide. Her friend texts Finn while he is in a hospice in the Bronx visiting Max; “You must come,” she says, “it’s Lily.” Finn, a high school history teacher who has been put on administrative leave for what he describes to Max as “a lot of personal matters,” rushes back home to the Midwest, but it’s already too late. He goes to the cemetery to visit Lily’s grave and finds her wandering around like a living dead. That’s when Finn decides to take her away and drive her to a body farm in Knoxville, Tennessee, since he remembers Lily having talked about wanting her body to be given to science. It’s a bit of an unconventional road trip.

At a decrepit old inn along the way, Finn bathes Lily, washing away the dust and grime of the cemetery. It’s a tender act—the bathwater is “the perfect warmth,” Finn cradles “the dense sweet rot of her” as he slips her into the tub—and it sounds like caring for the sick. Reading these descriptions, I keep wondering what is really happening and whether this is all magical thinking, but as Finn describes Lily’s body, how “the odor of pond scum wafted off her teeth when she spoke,” I decide to take it at face value. This isn’t Finn projecting about the care he isn’t giving to his brother or how he couldn’t save Lily. Though the story glosses over Lily’s exact state (she is speaking, moving, quite fragile, as if she were ill, not deceased), the suspended belief is that she really is dead and at the same time she really is there in the passenger seat next to him. This is their second chance.

Moore writes this with piercing realism and humor that plays down just how serious her themes are. When Finn first walks down the hospice corridor, he reflects on the photos of people lining the walls, like a restaurant’s framed snapshots of the celebrities who dined there. “Died there,” Finn thinks to himself. The wit is not deployed exactly for character building (perhaps except for Max, who, at death’s door, is watching the World Series and assures Finn the Cubs will win it, “more curveballs than life”) but rather to help set up a world where life and death are discussed directly, away from myth and metaphor. When Finn asks “what is death like anyway?” Lily replies, “Kind of what you think. And kind of not what you think. . . . It’s sort of what you make of it.”

In the room where Finn bathes Lily, he finds a journal-in-letters that a nineteenth-century innkeeper called Elizabeth wrote to her dead sister. Elizabeth describes the daily life of the inn and her boarders (one of whom she murders in another eerie aside about the meeting of life and death). The journal is interwoven in short bursts throughout the book, starting much before readers discover its loose connection to the plot. The journal mirrors some of the novel’s themes: siblings, death, and how we keep on living. Elizabeth’s last letter to her deceased sister ends, “Ps: I used your ashes this past January outside on the icy stairs for the safe walking of the boarders. I felt strongly you wouldn’t mind being put to good use.” No second chances there. The left-behind can do that: they can miss, still acknowledge the never-coming-back.

The shocking practicality of the nineteenth-century innkeeper is contrasted with the uselessness of Finn, the twenty-first-century man who can’t let go. “I’m sad that you’re leaving. And that you didn’t have a good time,” he tells Lily. When he is with Max at the beginning of the book, he thinks I miss you already, man, but doesn’t say it. I’ve seen several of Moore’s characters struggle to utter something profound about their feelings and relate to the people around them, while their projections onto characters who are not there are described with precision and care. In Anagrams (1986), Moore’s experimental prose introduces and reintroduces a couple, Gerard and Benna, in multiple circumstances, the only constant being how they disappoint each other in every version of the story. In Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? (1994), the protagonist, Berie, tells her husband about her childhood friend Sils, while determining she will never be as close to anyone (definitely not her husband) as she was to Sils that one summer when they were teenagers.

I loved those early novels. Reading Moore’s characters as they scramble to describe their emotions in this witty, straightforward style that she employs, I see how it’s possible to ask the big questions of love and loss and answer them with small moments of humanity and doubt, not with metaphor, nor with grandiosity or large claims. I didn’t like I Am Homeless. I didn’t like having to decide what to believe, what not to follow. I wanted to shake Finn, to have more (or less) of the found-object journal, because, as is, its role in the novel feels inconclusive. I didn’t like it—but I still admired this proposal Moore puts forth on a sentence level. It’s an experiment in directness around a subject that feels impossible to describe. Why do people around me discuss their experiences (and mine) in terms of CDs and vinyl records and planetary imagery? It’s an attempt to connect, even knowing that language fails anyway. Metaphors can feel so insufficient. I can’t even remember scratched vinyls (I’m of the generation for whom records were a hazy memory, then perhaps a teenage affectation). Looking for expressions for love and life and death and coming up with “life is very little,” as Lily tells Finn, may seem uninspiring. But, even against all this loss, this search for the right words goes on. That’s something to love.

Orit Gat is an art critic and writer living in London whose work on contemporary art and digital culture has appeared in a variety of magazines. She is a contributing editor of the White Review and is working on her first book, If Anything Happens, an essay on football, love, and loss.