Ed Halter

Ed Halter

A show of video art catches some cathode rays.

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995, installation view. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1975–1995, SculptureCenter, 44-19 Purves Street, Long Island City, New York, through December 17, 2018

• • •

In the mid-1990s, when celebrations of cinema’s centenary intersected with the rise of digital media and the looming “death of film,” debates about the aesthetic and perceptual uniqueness of celluloid took on a new urgency. In the art world, too, film’s medium specificity eventually became part of the discourse, and 16mm projectors have (again) become a familiar sight in galleries and museums. Yet critical and curatorial engagements with the materiality of video—that electronic transmission against which film has been historically counterposed—have been undertaken with far less frequency. The exhibition Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1975–1995, currently on view at SculptureCenter, provides an exemplary corrective to this gap, presenting a finely tuned suite of artworks that employ once-familiar, now-obsolete cathode-ray tubes as their means of producing moving images.

Those cathode-ray tube (CRT) monitors—humming cubes of plastic, metal, and glass, often gracelessly large and heavy enough to break a gallery assistant’s back—can still be found in art spaces, particularly as platforms for older video work. But beginning about twenty years ago, they were displaced as the primary means of display, first by projection and, more recently, high-definition flat screens. Contemporary exhibition tends to favor an image that has minimized its technical support, whether a spectral rectangle beamed upon a wall, or the puissant luminance of the HD monitor, in which visible hardware has been reduced to a thin, painterly frame. Not so for the offerings on view at Before Projection, where the bulky thingness of tube displays, and their positioning as three-dimensional objects in the galleries, provides a phenomenological through line between otherwise formally disparate artworks.

Diana Thater, Snake River, 1994 (installation view). 3 video monitors, 3 media players, digital files, dimensions variable; 30 minutes each. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Many of the pieces create a kind of physicalized montage, with multiple monitors arranged in ways that draw out dialectical relationships between them. Diana Thater’s Snake River (1994) consists of three monitors, laid out in a rough line on the floor, showing variations on silent landscape footage; each is also tinted a different hue—red, green, or blue—alluding to the original components of analog color video. For her monochrome four-video series The New Embodied Sign Language (1973–76), Friederike Pezold uses a stack of monitors to create an approximation of a woman’s body, with one screen displaying a blinking eye, the next one down a puckering mouth, and beneath that two more channels displaying cartoonishly painted nipples and crotch. The total effect is that of a twitchy exquisite corpse, with an appropriately surrealist sense of fragmented erotics.

Mary Lucier, Equinox, 1979/2016 (installation view). 7-channel video installation with sound, dimensions variable; 33 minutes. Courtesy artist and Lennon, Weinberg, Inc. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

More complex interactions of content and platform are found in installations by Dara Birnbaum and Mary Lucier, both of which highlight the work of the camera. Birnbaum’s Attack Piece (1975) presents two monitors, installed head-high on facing walls. Both channels are black-and-white: one is a video of Super 8 film, shot by a series of artists (including Dan Graham), that reveals the results of each cameraperson whirling around a seated Birnbaum, whom we can see holding a 35mm still camera; the other is a transferred slideshow of the photos Birnbaum took of those who “attacked” her. In addition to its feminist repositioning of hunter and hunted, subject and object, the piece also comments on video’s role as a container for other media. Lucier’s elegiac Equinox (1979/2016) runs across seven monitors, arranged in increasing size, and set upon narrow gray pedestals in a darkened room. The screens show a series of seven videotapes of sunrises Lucier recorded atop a Manhattan building on consecutive mornings. By shooting directly into the sun, Lucier gradually damaged the camera’s internal mechanisms. As a result, the images devolve into abstraction, the final day appearing as a set of color blobs.

Ernst Caramelle, Video Ping-Pong, 1974 (installation view). 2-channel black-and-white video installation, 2 monitors, 2 media players, metal shelves, Ping-Pong table, paddles, and balls, dimensions variable; 45 minutes each. Courtesy the artist and Generali Foundation. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

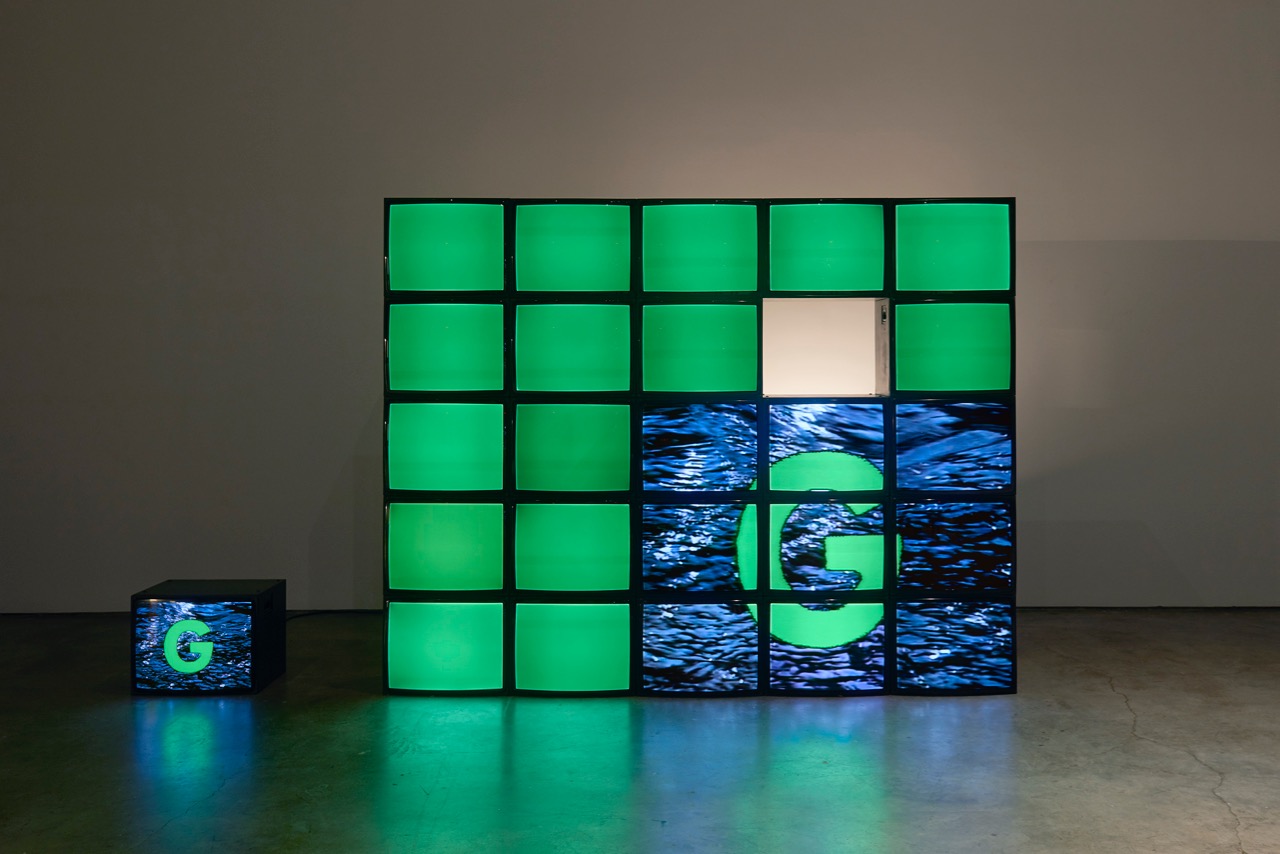

Some of these montage configurations play games with syncing between monitors. In Ernst Caramelle’s clever Video Ping-Pong (1974), two monitors installed on either side of a Ping-Pong table depict a table-tennis match that volleys invisibly from screen to screen. Caramelle’s elegant ludics seem positively minimalist when viewed next to Maria Vedder’s dazzling PAL oder Never The Same Color (1988), comprised of a video wall of twenty-four matching monitors with a twenty-fifth monitor positioned on the floor nearby, that used an early signal-switching system (here replicated via modern digital tech) to create a barrage of ever-changing images that spread out in an array of patterns. Vedder’s piece combines image processing, found footage, and an electronic score to yield a hyperactive study of color differences between American and European video standards.

Maria Vedder, PAL oder Never The Same Color, 1988 (installation view). Video installation with 25 monitors, sound, 7.6 × 13.7 × 1.2 feet; 5:32 minutes. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Other works in the show delve deeper into the physical qualities of CRT monitors through elaborate sculptural modifications, like Nam June Paik’s Charlotte Moorman II (1995), a cyborg figure made of antique televisions and a cello strung with RCA cables, or Shigeko Kubota’s River (1979–81), an assemblage of three monitors hanging above a brushed-steel wave pool, playing videos of colorful, synthesized shapes that wobble as reflections in the water—a coy reminder of the waveforms that make up analog video’s signal. Tony Oursler’s Psychomimetiscape II (1987) places miniature screens in a model of a two towers; one plays a tiny video essay with a poetic voice-over, mentioning alchemy and metallurgy, as perhaps another nod to the video signal’s fungibility.

Takahiko Iimura, TV for TV, 1983 (installation view). 2 identical monitors face to face, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Microscope Gallery. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

For all the technological ingenuity on hand here, however, one of the simplest works is also the most intriguing. Takahiko Iimura’s TV for TV (1983) is made up of nothing more than two televisions placed closely face-to-face, each tuned to a different channel, so that the screens provide just a narrow edge of flickering light. In its original iterations, Iimura’s piece must have included a variety of colors and movements from whatever was on the airways at the time, but now, years after the end of analog transmission, the sets play endless static. It’s the lone work in the exhibition that interacts with live broadcasts, yet they’re apparent only in their absence, thus presenting something of an electronic ruin, forever cut off from its originary moment. TV for TV helps sum up the exhibition as a whole, which provides a necessary, hardware-intensive reminder that the material of video has always consisted of much more than bodiless signals or digital data.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was recently published by Seven Stories Press.